The Ultimate Guide to Sail Boat Designs: Exploring Sail Shape, Masts and Keel Types in 2023

- June 4, 2023

When it comes to sail boat designs, there is a wide array of options available, each with its own unique characteristics and advantages. From the shape of the sails to the number of masts and the type of keel, every aspect plays a crucial role in determining a sailboat’s performance, stability, and manoeuvrability. In this comprehensive guide, we will delve into the fascinating world of sail boat designs, exploring the various elements and their significance.

Table of Contents

The sail shape is a fundamental aspect of sail boat design, directly impacting its speed, windward performance, and maneuverability. There are several types of sail shapes, including:

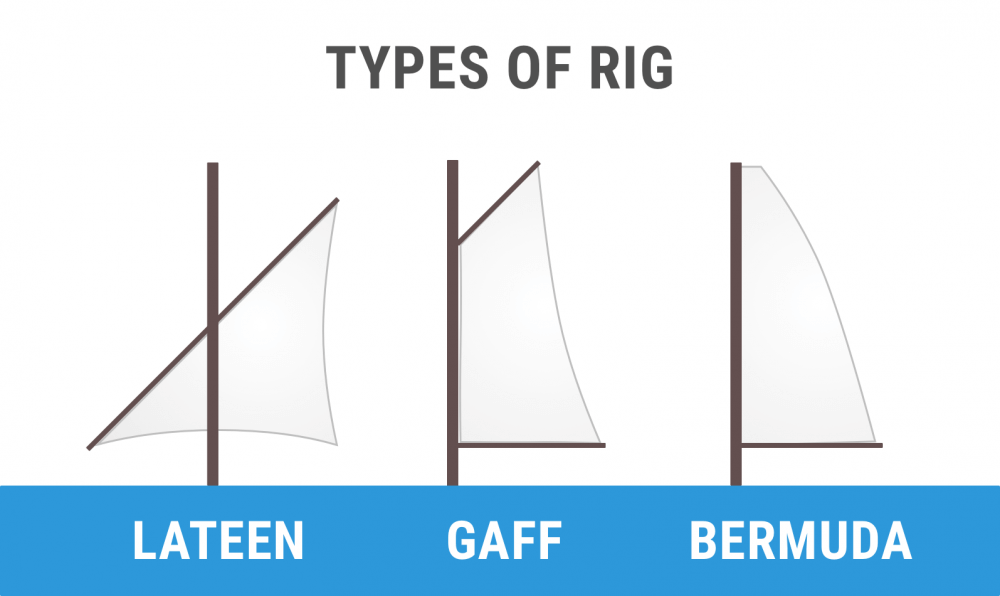

1. Bermuda Rig:

The Bermuda rig is a widely used sail shape known for its versatility and performance. It features a triangular mainsail and a jib, offering excellent maneuverability and the ability to sail close to the wind. The Bermuda rig’s design allows for efficient use of wind energy, enabling sailboats to achieve higher speeds. The tall, triangular mainsail provides a larger surface area for capturing the wind, while the jib helps to balance the sail plan and optimize performance. This rig is commonly found in modern recreational sailboats and racing yachts. Its sleek and streamlined appearance adds to its aesthetic appeal, making it a popular choice among sailors of all levels of experience.

2. Gaff Rig:

The Gaff rig is a classic sail shape that exudes elegance and nostalgia. It features a four-sided mainsail with a gaff and a topsail, distinguishing it from other sail designs. The gaff, a horizontal spar, extends diagonally from the mast, providing additional area for the mainsail. This configuration allows for a taller and more powerful sail, making the Gaff rig particularly suited for downwind sailing. The Gaff rig offers a traditional aesthetic and is often found in vintage and classic sailboats, evoking a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era of maritime exploration. The distinctive shape of the Gaff rig, with its graceful curves and intricate rigging, adds a touch of timeless charm to any sailboat that dons this rig.

3. Lateen Rig:

The Lateen rig is a unique and versatile sail design that has been used for centuries in various parts of the world. It features a triangular sail that is rigged on a long yard, extending diagonally from the mast. This configuration allows for easy adjustment of the sail’s angle to catch the wind efficiently, making the Lateen rig suitable for a wide range of wind conditions. The Lateen rig is known for its ability to provide both power and maneuverability, making it ideal for small to medium-sized sailboats and traditional vessels like dhow boats. Its versatility allows sailors to navigate narrow waterways and make tight turns with ease. The distinctive silhouette of a sailboat with a Lateen rig, with its sleek triangular sail and graceful curves, evokes a sense of adventure and a connection to seafaring traditions from around the world.

Number of Masts

The number of masts in a sail boat design affects its stability, sail area, and overall performance. Let’s explore a few common configurations:

1. Sloop Rig:

The sloop rig is one of the most popular and versatile sail boat designs, favoured by sailors around the world. It consists of a single mast and two sails—a mainsail and a jib. The sloop rig offers simplicity, ease of handling, and excellent performance across various wind conditions. The mainsail, situated behind the mast, provides the primary driving force, while the jib helps to balance the sail plan and improve manoeuvrability. This configuration allows for efficient upwind sailing, as the sails can be trimmed independently to optimize performance. The sloop rig is commonly found in modern recreational sailboats due to its versatility, enabling sailors to enjoy cruising, racing, or day sailing with ease. Its streamlined design and sleek appearance on the water make it both aesthetically pleasing and efficient, capturing the essence of the sailing experience.

2. Cutter Rig:

The cutter rig is a versatile and robust sail boat design that offers excellent performance, especially in challenging weather conditions. It features a single mast and multiple headsails, typically including a larger headsail forward of the mast, known as the cutter rig’s distinguishing feature. This configuration provides a wide range of sail combinations, enabling sailors to adjust the sail plan to suit varying wind strengths and directions. The larger headsail enhances the boat’s downwind performance, while the smaller headsails offer increased flexibility and improved balance. The cutter rig excels in heavy weather, as it allows for easy reefing and depowering by simply reducing or eliminating the headsails. This design is commonly found in offshore cruising sailboats and has a strong reputation for its reliability and seaworthiness. The cutter rig combines versatility, stability, and the ability to handle adverse conditions, making it a preferred choice for sailors seeking both performance and safety on their voyages.

3. Ketch Rig:

The Ketch rig is a sail boat design characterized by the presence of two masts, with the main mast being taller than the mizzen mast. This configuration offers a divided sail plan, providing sailors with increased flexibility, balance, and versatility. The main advantage of the Ketch rig is the ability to distribute the sail area across multiple sails, allowing for easier handling and reduced stress on each individual sail. The mizzen mast, positioned aft of the main mast, helps to improve the sailboat’s balance, especially in strong winds or when sailing downwind. The Ketch rig is often favoured by cruisers and long-distance sailors as it provides a range of sail combinations suitable for various wind conditions. With its distinctive double-mast appearance, the Ketch rig exudes a classic charm and is well-regarded for its stability, comfort, and suitability for extended journeys on the open seas.

The keel is the part of the sail boat that provides stability and prevents drifting sideways due to the force of the wind. Here are some common keel types:

1. Fin Keel:

The fin keel is a popular keel type in sail boat design known for its excellent upwind performance and stability. It is a long, narrow keel that extends vertically from the sailboat’s hull, providing a substantial amount of ballast to counterbalance the force of the wind. The fin keel’s streamlined shape minimizes drag and enables the sailboat to cut through the water with efficiency. This design enhances the sailboat’s ability to sail close to the wind, making it ideal for racing and performance-oriented sailboats. The fin keel also reduces leeway, which refers to the sideways movement of the boat caused by the wind. This improves the sailboat’s ability to maintain a straight course and enhances overall manoeuvrability. Sailboats with fin keels are commonly found in coastal and offshore racing as well as cruising vessels, where stability and responsiveness are valued. The fin keel’s combination of performance, stability, and reduced leeway makes it a preferred choice for sailors seeking speed and agility on the water.

2. Full Keel:

The full keel is a design known for its exceptional stability and seaworthiness. It extends along the entire length of the sailboat, providing a continuous surface that adds substantial weight and ballast. This configuration offers significant advantages in terms of tracking and resistance to drifting sideways. The full keel’s deep draft helps to prevent leeway and allows the sailboat to maintain a steady course even in adverse conditions. Its robust construction enhances the sailboat’s ability to handle heavy seas and provides a comfortable ride for sailors on extended journeys. While full keel sailboats may sacrifice some manoeuvrability, their stability and predictable handling make them a popular choice for offshore cruising and long-distance voyages. The full keel design has stood the test of time and is often associated with classic and traditional sailboat aesthetics, appealing to sailors seeking reliability, comfort, and the ability to tackle challenging ocean passages with confidence.

3. Wing Keel:

The wing keel is a unique keel design that offers a combination of reduced draft and improved stability. It features a bulbous extension or wings on the bottom of the keel, which effectively increases the keel’s surface area. This design allows sailboats to navigate in shallower waters without sacrificing stability and performance. The wings create additional lift and prevent excessive leeway, enhancing the sailboat’s upwind capabilities. The reduced draft of the wing keel enables sailors to explore coastal areas and anchor in shallower anchorages that would be inaccessible to sailboats with deeper keels. The wing keel is particularly well-suited for sailboats in areas with variable water depths or tidal ranges. This keel design offers the advantages of increased manoeuvrability and improved performance while maintaining stability, making it a popular choice for sailors seeking versatility in a range of sailing environments.

In the vast world of sail boat designs, sail shape, number of masts, and keel types play pivotal roles in determining a boat’s performance and handling characteristics. Whether you’re a recreational sailor, a racer, or a cruiser, understanding these design elements can help you make informed choices when selecting a sailboat.

Remember to consider your specific needs, preferences, and intended use of the boat when choosing a sail boat design. Each design has its strengths and weaknesses, and finding the perfect combination will greatly enhance your sailing experience.

By gaining a deeper understanding of sail boat designs, you can embark on your next sailing adventure with confidence and make the most of the wind’s power.

Related Posts

Sailing Navigation: Exploring Modern Techniques for Navigating the Seas in 2023

- June 10, 2023

Sailing in Different Directions: Harnessing the Wind’s Power in 2023

Sailing Terms Demystified: A Comprehensive Guide to 14 Common Sailing Terminology

- May 28, 2023

INTRODUCTION TO SAILBOAT DESIGN: A TECHNICAL EXPLORATION

Sailboat design is a complex and fascinating field that blends engineering, hydrodynamics, and aesthetics to create vessels that harness the power of the wind for propulsion. In this highly technical article, we will delve into the key aspects of sailboat design, from methodology to evaluation.

1) Design Methodology

Designing a sailboat is a meticulous process that begins with defining the vessel’s purpose and performance goals. It involves understanding the intended use, whether it’s racing, cruising, or a combination of both. Sailboat designers must also consider regulatory requirements and safety standards.

Once the design objectives are established, naval architects employ various computational tools and simulations to create a preliminary design. These tools help in predicting the boat’s performance characteristics and optimizing its geometry.

Design methodology also encompasses market research to understand current trends and customer preferences. This information is critical for creating a sailboat that appeals to potential buyers.

2) Hull Design

The hull is the heart of any sailboat. Its shape determines how the boat interacts with the water. Hull design encompasses the choice of hull form, its dimensions, and the material used. The hull’s shape affects its hydrodynamic performance, stability, and overall handling.

For example, a narrow hull design with a deep V-shape is ideal for speed, while a wider, flatter hull provides stability for cruising. The choice of materials, such as fiberglass or aluminum, impacts the boat’s weight and durability.

The hull design is a balance between achieving efficient hydrodynamics and providing interior space for accommodations. As a designer, finding this equilibrium is a constant challenge.

3) Keel & Rudder Design

The keel and rudder are critical components of a sailboat’s underwater structure. The keel provides stability by preventing the boat from tipping over, while the rudder controls its direction. Keel design involves selecting the keel type (fin, bulb, or wing) and optimizing its shape for maximum hydrodynamic efficiency.

Rudder’s design focuses on ensuring precise control and maneuverability. Both components must be carefully integrated into the hull’s design to maintain balance and performance.

Keel and rudder design can be particularly challenging because they influence the boat’s behavior in different ways. A well-designed keel adds stability but also increases draft, limiting where the boat can sail. Rudder design must account for both responsiveness and the risk of stalling at high speeds.

4) Sail & Rig Design

Sail and rig design play a pivotal role in harnessing wind power. Sail choice, size, and shape are tailored to the boat’s intended use and performance goals. Modern sail materials like carbon fiber offer lightweight and durable options.

The rig design involves selecting the type of mast (single or multiple), rigging configuration, and mast height. These choices influence the sailboat’s stability, maneuverability, and ability to handle varying wind conditions.

Balancing the sails and rig for optimal performance is a meticulous task. The sail plan should be designed to efficiently convert wind energy into forward motion while allowing for easy adjustments to adapt to changing conditions.

5) Balance

Balancing a sailboat is crucial for its performance and safety. Achieving the right balance involves a delicate interplay between the hull, keel, rudder, and sail plan. Proper balance ensures the boat remains stable and responds predictably to helm inputs, even in changing wind conditions.

Balance is not a static concept but something that evolves as the boat sails in different wind and sea conditions. Designers must anticipate how changes in load, wind angle, and sail trim will affect the boat’s balance.

Achieving balance is both an art and a science, and it often requires iterative adjustments during the design and testing phases to achieve optimal results.

6) Propulsion

While sailboats primarily rely on wind propulsion, auxiliary propulsion systems like engines are essential for maneuvering in harbors or during calm conditions. Integrating propulsion systems seamlessly into the boat’s design requires careful consideration of engine placement, fuel storage, and exhaust systems.

The choice of propulsion system, whether it’s a traditional diesel engine or a more eco-friendly electric motor, also impacts the boat’s weight distribution and overall performance.

7) Scantling

Scantling refers to the selection of structural components and their dimensions to ensure the boat’s strength and integrity. It involves determining the appropriate thickness of the hull, deck, and other structural elements to withstand the stresses encountered at sea.

Scantling is a critical aspect of sailboat design, as it directly relates to safety. A well-designed boat must be able to withstand the forces exerted on it by waves, wind, and other environmental factors.

8) Stability

Stability is a critical safety factor in sailboat design. Both upright hydrostatics and large-angle stability must be carefully assessed and optimized. This involves evaluating the boat’s center of gravity, ballast, and hull shape.

Achieving the right balance between initial stability, which provides comfort to passengers, and ultimate stability, which ensures safety in adverse conditions, is a delicate task. Designers often use stability curves and computer simulations to fine-tune these characteristics.

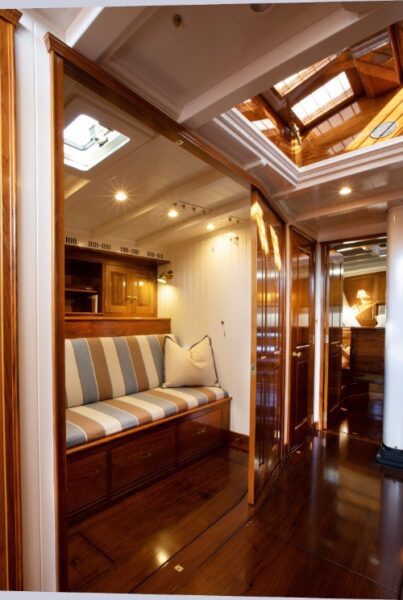

9) Layout

The layout of a sailboat’s interior and deck spaces is a blend of functionality and comfort. Designers must consider the ergonomics of living and working aboard the vessel, including cabin layout, galley design, and storage solutions. The deck layout influences crew movements and sail handling.

Layout design also extends to considerations like ventilation, lighting, and noise control. Sailboats are unique in that they must provide both comfortable living spaces and efficient workspaces for handling sails and navigation.

10) Design Evaluation

The final phase of sailboat design involves rigorous evaluation and testing. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, tank testing, and real-world sea trials help validate the design’s performance predictions. Any necessary adjustments are made to fine-tune the vessel’s behavior on the water.

The evaluation phase is where the theoretical aspects of design meet the practical realities of the sea. It’s a crucial step in ensuring that the sailboat not only meets but exceeds its performance and safety expectations.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, sailboat design is a highly technical field that requires a deep understanding of hydrodynamics, engineering principles, and materials science. Naval architects and yacht designers meticulously navigate through the intricacies of hull design, keel and rudder configuration, sail and rig design, balance, propulsion, scantling, stability, layout, and design evaluation to create vessels that excel in both form and function. The harmonious integration of these elements results in sailboats that are not just seaworthy but also a joy to sail, and this process is a testament to the art and science of sailboat design.

Click here to read about “ HARNESSING THE POWER OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN BOAT DESIGN “

Follow my Linkedin Newsletter here: “LinkedIn Newsletter”

0 comments Leave a reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

- KEY LESSONS I LEARNED FROM MY FREELANCE JOURNEY IN 2023

- THE FREELANCE ECONOMY: KEY TRENDS AND PREDICTIONS FOR 2024

- THE RISE Of HDPE IN BOAT MANUFACTURING: TRENDS & BENEFITS

- THE CRITICAL ROLE OF FEASIBILITY STUDY IN BOAT DESIGN AND NAVAL ARCHITECTURE

- THE CHALLENGES Of SMALL CRAFT DESIGN COMPARED TO LARGER VESSELS

Recent Comments

- Casey Lim on HDPE BOAT PLANS

- BRYN BONGBONG on HDPE BOAT PLANS

- Keith on HDPE BOAT PLANS

- Daniel Desauriers on WHY HDPE BOATS?

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- September 2022

- January 2021

- ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

- boatbuilder

- BOAT CONSTRUCTION TECHNIQUES

- BOAT DESIGN COST

- boatdesign process

- CAREER PATHWAYS

- COMMERCIAL BOATS

- conventional boats

- custom boat

- DESIGN ADMINISTRATION

- DESIGN SPIRAL

- EXTREME CONDITIONS

- FEASIBILITY STUDY

- Freelance advantage

- freelance boat designer

- FREELANCE ECONOMY

- FREELANCE JOURNEY

- FRP Boat without Mold

- HDPE Collar

- INDIA'S MARITIME

- INVENTORY MANAGEMENT

- ISO STANDARDS

- Mass Production

- Monhull vs Catamaran

- Naval Architect

- Naval Architecture

- PLANING HULL

- Project Management

- Proven Hull

- PSYCHOLOGY OF BOAT DESIGN

- QUALITY CONTROL

- RECREATIONAL BOATS

- RISE OF HDPE

- ROYALTY AGREEMENTS

- SANDWICH VS SINGLE SKIN

- SOLOPRENEUR

- YACHT DESIGN COURSE

The Ultimate Guide to Sail Types and Rigs (with Pictures)

What's that sail for? Generally, I don't know. So I've come up with a system. I'll explain you everything there is to know about sails and rigs in this article.

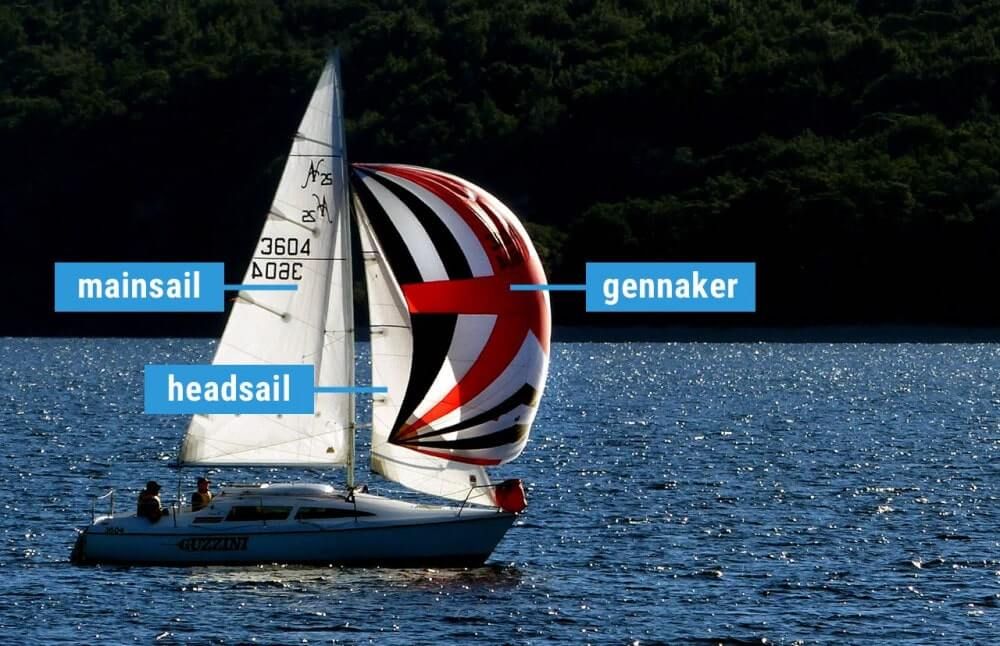

What are the different types of sails? Most sailboats have one mainsail and one headsail. Typically, the mainsail is a fore-and-aft bermuda rig (triangular shaped). A jib or genoa is used for the headsail. Most sailors use additional sails for different conditions: the spinnaker (a common downwind sail), gennaker, code zero (for upwind use), and stormsail.

Each sail has its own use. Want to go downwind fast? Use a spinnaker. But you can't just raise any sail and go for it. It's important to understand when (and how) to use each sail. Your rigging also impacts what sails you can use.

On this page:

Different sail types, the sail plan of a bermuda sloop, mainsail designs, headsail options, specialty sails, complete overview of sail uses, mast configurations and rig types.

This article is part 1 of my series on sails and rig types. Part 2 is all about the different types of rigging. If you want to learn to identify every boat you see quickly, make sure to read it. It really explains the different sail plans and types of rigging clearly.

Guide to Understanding Sail Rig Types (with Pictures)

First I'll give you a quick and dirty overview of sails in this list below. Then, I'll walk you through the details of each sail type, and the sail plan, which is the godfather of sail type selection so to speak.

Click here if you just want to scroll through a bunch of pictures .

Here's a list of different models of sails: (Don't worry if you don't yet understand some of the words, I'll explain all of them in a bit)

- Jib - triangular staysail

- Genoa - large jib that overlaps the mainsail

- Spinnaker - large balloon-shaped downwind sail for light airs

- Gennaker - crossover between a Genoa and Spinnaker

- Code Zero or Screecher - upwind spinnaker

- Drifter or reacher - a large, powerful, hanked on genoa, but made from lightweight fabric

- Windseeker - tall, narrow, high-clewed, and lightweight jib

- Trysail - smaller front-and-aft mainsail for heavy weather

- Storm jib - small jib for heavy weather

I have a big table below that explains the sail types and uses in detail .

I know, I know ... this list is kind of messy, so to understand each sail, let's place them in a system.

The first important distinction between sail types is the placement . The mainsail is placed aft of the mast, which simply means behind. The headsail is in front of the mast.

Generally, we have three sorts of sails on our boat:

- Mainsail: The large sail behind the mast which is attached to the mast and boom

- Headsail: The small sail in front of the mast, attached to the mast and forestay (ie. jib or genoa)

- Specialty sails: Any special utility sails, like spinnakers - large, balloon-shaped sails for downwind use

The second important distinction we need to make is the functionality . Specialty sails (just a name I came up with) each have different functionalities and are used for very specific conditions. So they're not always up, but most sailors carry one or more of these sails.

They are mostly attached in front of the headsail, or used as a headsail replacement.

The specialty sails can be divided into three different categories:

- downwind sails - like a spinnaker

- light air or reacher sails - like a code zero

- storm sails

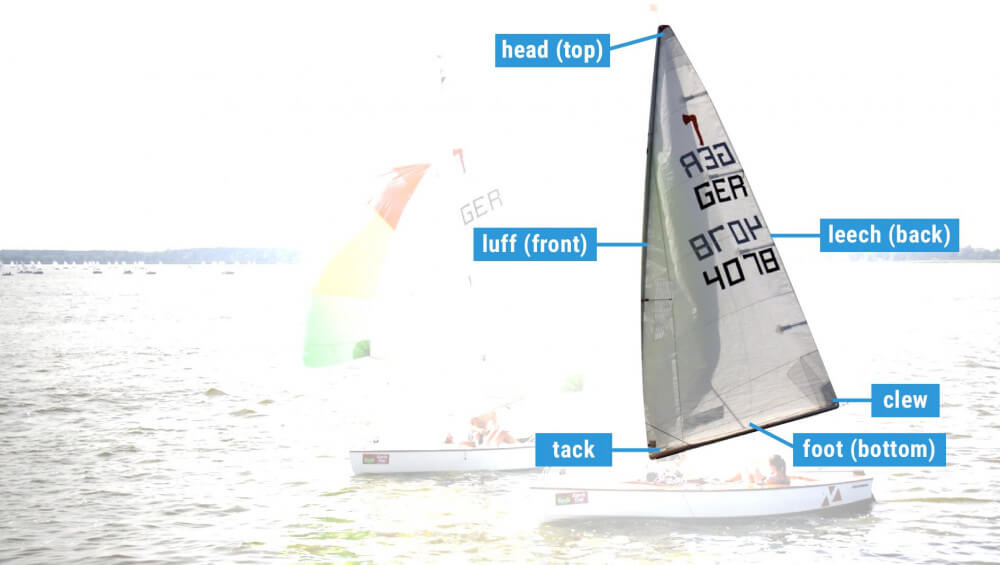

The parts of any sail

Whether large or small, each sail consists roughly of the same elements. For clarity's sake I've took an image of a sail from the world wide webs and added the different part names to it:

- Head: Top of the sail

- Tack: Lower front corner of the sail

- Foot: Bottom of the sail

- Luff: Forward edge of the sail

- Leech: Back edge of the sail

- Clew: Bottom back corner of the sail

So now we speak the same language, let's dive into the real nitty gritty.

Basic sail shapes

Roughly speaking, there are actually just two sail shapes, so that's easy enough. You get to choose from:

- square rigged sails

- fore-and-aft rigged sails

I would definitely recommend fore-and-aft rigged sails. Square shaped sails are pretty outdated. The fore-and-aft rig offers unbeatable maneuverability, so that's what most sailing yachts use nowadays.

Square sails were used on Viking longships and are good at sailing downwind. They run from side to side. However, they're pretty useless upwind.

A fore-and-aft sail runs from the front of the mast to the stern. Fore-and-aft literally means 'in front and behind'. Boats with fore-and-aft rigged sails are better at sailing upwind and maneuvering in general. This type of sail was first used on Arabic boats.

As a beginner sailor I confuse the type of sail with rigging all the time. But I should cut myself some slack, because the rigging and sails on a boat are very closely related. They are all part of the sail plan .

A sail plan is made up of:

- Mast configuration - refers to the number of masts and where they are placed

- Sail type - refers to the sail shape and functionality

- Rig type - refers to the way these sails are set up on your boat

There are dozens of sails and hundreds of possible configurations (or sail plans).

For example, depending on your mast configuration, you can have extra headsails (which then are called staysails).

The shape of the sails depends on the rigging, so they overlap a bit. To keep it simple I'll first go over the different sail types based on the most common rig. I'll go over the other rig types later in the article.

Bermuda Sloop: the most common rig

Most modern small and mid-sized sailboats have a Bermuda sloop configuration . The sloop is one-masted and has two sails, which are front-and-aft rigged. This type of rig is also called a Marconi Rig. The Bermuda rig uses a triangular sail, with just one side of the sail attached to the mast.

The mainsail is in use most of the time. It can be reefed down, making it smaller depending on the wind conditions. It can be reefed down completely, which is more common in heavy weather. (If you didn't know already: reefing is skipper terms for rolling or folding down a sail.)

In very strong winds (above 30 knots), most sailors only use the headsail or switch to a trysail.

The headsail powers your bow, the mainsail powers your stern (rear). By having two sails, you can steer by using only your sails (in theory - it requires experience). In any case, two sails gives you better handling than one, but is still easy to operate.

Let's get to the actual sails. The mainsail is attached behind the mast and to the boom, running to the stern. There are multiple designs, but they actually don't differ that much. So the following list is a bit boring. Feel free to skip it or quickly glance over it.

- Square Top racing mainsail - has a high performance profile thanks to the square top, optional reef points

- Racing mainsail - made for speed, optional reef points

- Cruising mainsail - low-maintenance, easy to use, made to last. Generally have one or multiple reef points.

- Full-Batten Cruising mainsail - cruising mainsail with better shape control. Eliminates flogging. Full-length battens means the sail is reinforced over the entire length. Generally have one or multiple reef points.

- High Roach mainsail - crossover between square top racing and cruising mainsail, used mostly on cats and multihulls. Generally have one or multiple reef points.

- Mast Furling mainsail - sails specially made to roll up inside the mast - very convenient but less control; of sail shape. Have no reef points

- Boom Furling mainsail - sails specially made to roll up inside the boom. Have no reef points.

The headsail is the front sail in a front-and-aft rig. The sail is fixed on a stay (rope, wire or rod) which runs forward to the deck or bowsprit. It's almost always triangular (Dutch fishermen are known to use rectangular headsail). A triangular headsail is also called a jib .

Headsails can be attached in two ways:

- using roller furlings - the sail rolls around the headstay

- hank on - fixed attachment

Types of jibs:

Typically a sloop carries a regular jib as its headsail. It can also use a genoa.

- A jib is a triangular staysail set in front of the mast. It's the same size as the fore-triangle.

- A genoa is a large jib that overlaps the mainsail.

What's the purpose of a jib sail? A jib is used to improve handling and to increase sail area on a sailboat. This helps to increase speed. The jib gives control over the bow (front) of the ship, making it easier to maneuver the ship. The mainsail gives control over the stern of the ship. The jib is the headsail (frontsail) on a front-and-aft rig.

The size of the jib is generally indicated by a number - J1, 2, 3, and so on. The number tells us the attachment point. The order of attachment points may differ per sailmaker, so sometimes J1 is the largest jib (on the longest stay) and sometimes it's the smallest (on the shortest stay). Typically the J1 jib is the largest - and the J3 jib the smallest.

Most jibs are roller furling jibs: this means they are attached to a stay and can be reefed down single-handedly. If you have a roller furling you can reef down the jib to all three positions and don't need to carry different sizes.

Originally called the 'overlapping jib', the leech of the genoa extends aft of the mast. This increases speed in light and moderate winds. A genoa is larger than the total size of the fore-triangle. How large exactly is indicated by a percentage.

- A number 1 genoa is typically 155% (it used to be 180%)

- A number 2 genoa is typically 125-140%

Genoas are typically made from 1.5US/oz polyester spinnaker cloth, or very light laminate.

This is where it gets pretty interesting. You can use all kinds of sails to increase speed, handling, and performance for different weather conditions.

Some rules of thumb:

- Large sails are typically good for downwind use, small sails are good for upwind use.

- Large sails are good for weak winds (light air), small sails are good for strong winds (storms).

Downwind sails

Thanks to the front-and-aft rig sailboats are easier to maneuver, but they catch less wind as well. Downwind sails are used to offset this by using a large sail surface, pulling a sailboat downwind. They can be hanked on when needed and are typically balloon shaped.

Here are the most common downwind sails:

- Big gennaker

- Small gennaker

A free-flying sail that fills up with air, giving it a balloon shape. Spinnakers are generally colorful, which is why they look like kites. This downwind sail has the largest sail area, and it's capable of moving a boat with very light wind. They are amazing to use on trade wind routes, where they can help you make quick progress.

Spinnakers require special rigging. You need a special pole and track on your mast. You attach the sail at three points: in the mast head using a halyard, on a pole, and on a sheet.

The spinnaker is symmetrical, meaning the luff is as long as its leech. It's designed for broad reaching.

Gennaker or cruising spinnaker

The Gennaker is a cross between the genoa and the spinnaker. It has less downwind performance than the spinnaker. It is a bit smaller, making it slower, but also easier to handle - while it remains very capable. The cruising spinnaker is designed for broad reaching.

The gennaker is a smaller, asymmetric spinnaker that's doesn't require a pole or track on the mast. Like the spinnaker, and unlike the genoa, the gennaker is set flying. Asymmetric means its luff is longer than its leech.

You can get big and small gennakers (roughly 75% and 50% the size of a true spinnaker).

Also called ...

- the cruising spinnaker

- cruising chute

- pole-less spinnaker

- SpinDrifter

... it's all the same sail.

Light air sails

There's a bit of overlap between the downwind sails and light air sails. Downwind sails can be used as light air sails, but not all light air sails can be used downwind.

Here are the most common light air sails:

- Spinnaker and gennaker

Drifter reacher

Code zero reacher.

A drifter (also called a reacher) is a lightweight, larger genoa for use in light winds. It's roughly 150-170% the size of a genoa. It's made from very lightweight laminated spinnaker fabric (1.5US/oz).

Thanks to the extra sail area the sail offers better downwind performance than a genoa. It's generally made from lightweight nylon. Thanks to it's genoa characteristics the sail is easier to use than a cruising spinnaker.

The code zero reacher is officially a type of spinnaker, but it looks a lot like a large genoa. And that's exactly what it is: a hybrid cross between the genoa and the asymmetrical spinnaker (gennaker). The code zero however is designed for close reaching, making it much flatter than the spinnaker. It's about twice the size of a non-overlapping jib.

A windseeker is a small, free-flying staysail for super light air. It's tall and thin. It's freestanding, so it's not attached to the headstay. The tack attaches to a deck pad-eye. Use your spinnakers' halyard to raise it and tension the luff.

It's made from nylon or polyester spinnaker cloth (0.75 to 1.5US/oz).

It's designed to guide light air onto the lee side of the main sail, ensuring a more even, smooth flow of air.

Stormsails are stronger than regular sails, and are designed to handle winds of over 45 knots. You carry them to spare the mainsail. Sails

A storm jib is a small triangular staysail for use in heavy weather. If you participate in offshore racing you need a mandatory orange storm jib. It's part of ISAF's requirements.

A trysail is a storm replacement for the mainsail. It's small, triangular, and it uses a permanently attached pennant. This allows it to be set above the gooseneck. It's recommended to have a separate track on your mast for it - you don't want to fiddle around when you actually really need it to be raised ... now.

| Sail | Type | Shape | Wind speed | Size | Wind angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bermuda | mainsail | triangular, high sail | < 30 kts | ||

| Jib | headsail | small triangular foresail | < 45 kts | 100% of foretriangle | |

| Genoa | headsail | jib that overlaps mainsail | < 30 kts | 125-155% of foretriangle | |

| Spinnaker | downwind | free-flying, balloon shape | 1-15 kts | 200% or more of mainsail | 90°–180° |

| Gennaker | downwind | free-flying, balloon shape | 1-20 kts | 85% of spinnaker | 75°-165° |

| Code Zero or screecher | light air & upwind | tight luffed, upwind spinnaker | 1-16 kts | 70-75% of spinnaker | |

| Storm Trysail | mainsail | small triangular mainsail replacement | > 45 kts | 17.5% of mainsail | |

| Drifter reacher | light air | large, light-weight genoa | 1-15 kts | 150-170% of genoa | 30°-90° |

| Windseeker | light air | free-flying staysail | 0-6 kts | 85-100% of foretriangle | |

| Storm jib | strong wind headsail | low triangular staysail | > 45 kts | < 65% height foretriangle |

Why Use Different Sails At All?

You could just get the largest furling genoa and use it on all positions. So why would you actually use different types of sails?

The main answer to that is efficiency . Some situations require other characteristics.

Having a deeply reefed genoa isn't as efficient as having a small J3. The reef creates too much draft in the sail, which increases heeling. A reefed down mainsail in strong winds also increases heeling. So having dedicated (storm) sails is probably a good thing, especially if you're planning more demanding passages or crossings.

But it's not just strong winds, but also light winds that can cause problems. Heavy sails will just flap around like laundry in very light air. So you need more lightweight fabrics to get you moving.

What Are Sails Made Of?

The most used materials for sails nowadays are:

- Dacron - woven polyester

- woven nylon

- laminated fabrics - increasingly popular

Sails used to be made of linen. As you can imagine, this is terrible material on open seas. Sails were rotting due to UV and saltwater. In the 19th century linen was replaced by cotton.

It was only in the 20th century that sails were made from synthetic fibers, which were much stronger and durable. Up until the 1980s most sails were made from Dacron. Nowadays, laminates using yellow aramids, Black Technora, carbon fiber and Spectra yarns are more and more used.

Laminates are as strong as Dacron, but a lot lighter - which matters with sails weighing up to 100 kg (220 pounds).

By the way: we think that Viking sails were made from wool and leather, which is quite impressive if you ask me.

In this section of the article I give you a quick and dirty summary of different sail plans or rig types which will help you to identify boats quickly. But if you want to really understand it clearly, I really recommend you read part 2 of this series, which is all about different rig types.

You can't simply count the number of masts to identify rig type But you can identify any rig type if you know what to look for. We've created an entire system for recognizing rig types. Let us walk you through it. Read all about sail rig types

As I've said earlier, there are two major rig types: square rigged and fore-and-aft. We can divide the fore-and-aft rigs into three groups:

- Bermuda rig (we have talked about this one the whole time) - has a three-sided mainsail

- Gaff rig - has a four-sided mainsail, the head of the mainsail is guided by a gaff

- Lateen rig - has a three-sided mainsail on a long yard

There are roughly four types of boats:

- one masted boats - sloop, cutter

- two masted boats - ketch, schooner, brig

- three masted - barque

- fully rigged or ship rigged - tall ship

Everything with four masts is called a (tall) ship. I think it's outside the scope of this article, but I have written a comprehensive guide to rigging. I'll leave the three and four-masted rigs for now. If you want to know more, I encourage you to read part 2 of this series.

One-masted rigs

Boats with one mast can have either one sail, two sails, or three or more sails.

The 3 most common one-masted rigs are:

- Cat - one mast, one sail

- Sloop - one mast, two sails

- Cutter - one mast, three or more sails

1. Gaff Cat

2. Gaff Sloop

Two-masted rigs

Two-masted boats can have an extra mast in front or behind the main mast. Behind (aft of) the main mast is called a mizzen mast . In front of the main mast is called a foremast .

The 5 most common two-masted rigs are:

- Lugger - two masts (mizzen), with lugsail (cross between gaff rig and lateen rig) on both masts

- Yawl - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast much taller than mizzen. Mizzen without mainsail.

- Ketch - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller mizzen. Mizzen has mainsail.

- Schooner - two masts (foremast), generally gaff rig on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller foremast. Sometimes build with three masts, up to seven in the age of sail.

- Brig - two masts (foremast), partially square-rigged. Main mast carries small lateen rigged sail.

4. Schooner

5. Brigantine

This article is part 1 of a series about sails and rig types If you want to read on and learn to identify any sail plans and rig type, we've found a series of questions that will help you do that quickly. Read all about recognizing rig types

Related Questions

What is the difference between a gennaker & spinnaker? Typically, a gennaker is smaller than a spinnaker. Unlike a spinnaker, a gennaker isn't symmetric. It's asymmetric like a genoa. It is however rigged like a spinnaker; it's not attached to the forestay (like a jib or a genoa). It's a downwind sail, and a cross between the genoa and the spinnaker (hence the name).

What is a Yankee sail? A Yankee sail is a jib with a high-cut clew of about 3' above the boom. A higher-clewed jib is good for reaching and is better in high waves, preventing the waves crash into the jibs foot. Yankee jibs are mostly used on traditional sailboats.

How much does a sail weigh? Sails weigh anywhere between 4.5-155 lbs (2-70 kg). The reason is that weight goes up exponentially with size. Small boats carry smaller sails (100 sq. ft.) made from thinner cloth (3.5 oz). Large racing yachts can carry sails of up to 400 sq. ft., made from heavy fabric (14 oz), totaling at 155 lbs (70 kg).

What's the difference between a headsail and a staysail? The headsail is the most forward of the staysails. A boat can only have one headsail, but it can have multiple staysails. Every staysail is attached to a forward running stay. However, not every staysail is located at the bow. A stay can run from the mizzen mast to the main mast as well.

What is a mizzenmast? A mizzenmast is the mast aft of the main mast (behind; at the stern) in a two or three-masted sailing rig. The mizzenmast is shorter than the main mast. It may carry a mainsail, for example with a ketch or lugger. It sometimes doesn't carry a mainsail, for example with a yawl, allowing it to be much shorter.

Special thanks to the following people for letting me use their quality photos: Bill Abbott - True Spinnaker with pole - CC BY-SA 2.0 lotsemann - Volvo Ocean Race Alvimedica and the Code Zero versus SCA and the J1 - CC BY-SA 2.0 Lisa Bat - US Naval Academy Trysail and Storm Jib dry fit - CC BY-SA 2.0 Mike Powell - White gaff cat - CC BY-SA 2.0 Anne Burgess - Lugger The Reaper at Scottish Traditional Boat Festival

Hi, I stumbled upon your page and couldn’t help but notice some mistakes in your description of spinnakers and gennakers. First of all, in the main photo on top of this page the small yacht is sailing a spinnaker, not a gennaker. If you look closely you can see the spinnaker pole standing on the mast, visible between the main and headsail. Further down, the discription of the picture with the two German dinghies is incorrect. They are sailing spinnakers, on a spinnaker pole. In the farthest boat, you can see a small piece of the pole. If needed I can give you the details on the difference between gennakers and spinnakers correctly?

Hi Shawn, I am living in Utrecht I have an old gulf 32 and I am sailing in merkmeer I find your articles very helpful Thanks

Thank you for helping me under stand all the sails there names and what there functions were and how to use them. I am planning to build a trimaran 30’ what would be the best sails to have I plan to be coastal sailing with it. Thank you

Hey Comrade!

Well done with your master piece blogging. Just a small feedback. “The jib gives control over the bow of the ship, making it easier to maneuver the ship. The mainsail gives control over the stern of the ship.” Can you please first tell the different part of a sail boat earlier and then talk about bow and stern later in the paragraph. A reader has no clue on the newly introduced terms. It helps to keep laser focused and not forget main concepts.

Shawn, I am currently reading How to sail around the World” by Hal Roth. Yes, I want to sail around the world. His book is truly grounded in real world experience but like a lot of very knowledgable people discussing their area of expertise, Hal uses a lot of terms that I probably should have known but didn’t, until now. I am now off to read your second article. Thank You for this very enlightening article on Sail types and their uses.

Shawn Buckles

HI CVB, that’s a cool plan. Thanks, I really love to hear that. I’m happy that it was helpful to you and I hope you are of to a great start for your new adventure!

Hi GOWTHAM, thanks for the tip, I sometimes forget I haven’t specified the new term. I’ve added it to the article.

Nice article and video; however, you’re mixing up the spinnaker and the gennaker.

A started out with a question. What distinguishes a brig from a schooner? Which in turn led to follow-up questions: I know there are Bermuda rigs and Latin rig, are there more? Which in turn led to further questions, and further, and further… This site answers them all. Wonderful work. Thank you.

Great post and video! One thing was I was surprised how little you mentioned the Ketch here and not at all in the video or chart, and your sample image is a large ship with many sails. Some may think Ketch’s are uncommon, old fashioned or only for large boats. Actually Ketch’s are quite common for cruisers and live-aboards, especially since they often result in a center cockpit layout which makes for a very nice aft stateroom inside. These are almost exclusively the boats we are looking at, so I was surprised you glossed over them.

Love the article and am finding it quite informative.

While I know it may seem obvious to 99% of your readers, I wish you had defined the terms “upwind” and “downwind.” I’m in the 1% that isn’t sure which one means “with the wind” (or in the direction the wind is blowing) and which one means “against the wind” (or opposite to the way the wind is blowing.)

paul adriaan kleimeer

like in all fields of syntax and terminology the terms are colouual meaning local and then spead as the technology spread so an history lesson gives a floral bouque its colour and in the case of notical terms span culture and history adds an detail that bring reverence to the study simply more memorable.

Hi, I have a small yacht sail which was left in my lock-up over 30 years ago I basically know nothing about sails and wondered if you could spread any light as to the make and use of said sail. Someone said it was probably originally from a Wayfayer wooden yacht but wasn’t sure. Any info would be must appreciated and indeed if would be of any use to your followers? I can provide pics but don’t see how to include them at present

kind regards

Leave a comment

You may also like, 17 sailboat types explained: how to recognize them.

Ever wondered what type of sailboat you're looking at? Identifying sailboats isn't hard, you just have to know what to look for. In this article, I'll help you.

How Much Sailboats Cost On Average (380+ Prices Compared)

Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

25 of the best small sailing boat designs

- Nic Compton

- August 10, 2022

Nic Compton looks at the 25 yachts under 40ft which have had the biggest impact on UK sailing

There’s nothing like a list of best small sailing boat designs to get the blood pumping.

Everyone has their favourites, and everyone has their pet hates.

This is my list of the 25 best small sailing boat designs, honed down from the list of 55 yachts I started with.

I’ve tried to be objective and have included several boats I don’t particularly like but which have undeniably had an impact on sailing in the UK – and yes, it would be quite a different list if I was writing about another country.

If your favourite isn’t on the best small sailing boat designs list, then send an email to [email protected] to argue the case for your best-loved boat.

Ready? Take a deep breath…

Credit: Bob Aylott

Laurent Giles is best known for designing wholesome wooden cruising boats such as the Vertue and Wanderer III , yet his most successful design was the 26ft Centaur he designed for Westerly, of which a remarkable 2,444 were built between 1969 and 1980.

It might not be the prettiest boat on the water, but it sure packs a lot of accommodation.

The Westerly Centaur was one of the first production boats to be tank tested, so it sails surprisingly well too. Jack L Giles knew what he was doing.

Colin Archer

Credit: Nic Compton

Only 32 Colin Archer lifeboats were built during their designer’s lifetime, starting with Colin Archer in 1893 and finishing with Johan Bruusgaard in 1924.

Yet their reputation for safety spawned hundreds of copycat designs, the most famous of which was Sir Robin Knox-Johnston ’s Suhaili , which he sailed around the world singlehanded in 1968-9.

The term Colin Archer has become so generic it is often used to describe any double-ender – so beware!

Contessa 32

Assent ‘s performance in the 1979 Fastnet Race makes the Contessa 32 a worth entry in the 25 best small sailing boat designs list. Credit: Nic Compton

Designed by David Sadler as a bigger alternative to the popular Contessa 26, the Contessa 32 was built by Jeremy Rogers in Lymington from 1970.

The yacht’s credentials were established when Assent , the Contessa 32 owned by Willy Kerr and skippered by his son Alan, became the only yacht in her class to complete the deadly 1979 Fastnet Race .

When UK production ceased in 1983, more than 700 had been built, and another 20 have been built since 1996.

Cornish Crabber 24

It seemed a daft idea to build a gaff-rigged boat in 1974, just when everyone else had embraced the ‘modern’ Bermudan rig.

Yet the first Cornish Crabber 24, designed by Roger Dongray, tapped into a feeling that would grow and grow and eventually become a movement.

The 24 was followed in 1979 by the even more successful Shrimper 19 – now ubiquitous in almost every harbour in England – and the rest is history.

Drascombe Lugger

Credit: David Harding

There are faster, lighter and more comfortable boats than a Drascombe Lugger.

And yet, 57 years after John Watkinson designed the first ‘lugger’ (soon changed to gunter rig), more than 2,000 have been built and the design is still going strong.

More than any other boat, the Drascombe Lugger opened up dinghy cruising, exemplified by Ken Duxbury’s Greek voyages in the 1970s and Webb Chiles’s near-circumnavigation on Chidiock Tichbourne I and II .

The 26ft Eventide. Credit: David Harding

It’s been described as the Morris Minor of the boating world – except that the majority of the 1,000 Eventides built were lovingly assembled by their owners, not on a production line.

After you’d tested your skills building the Mirror dinghy, you could progress to building a yacht.

And at 24ft long, the Eventide packed a surprising amount of living space.

It was Maurice Griffiths’ most successful design and helped bring yachting to a wider audience.

You either love ’em or you hate ’em – motorsailers, that is.

The Fisher 30 was brought into production in 1971 and was one of the first out-and-out motorsailers.

With its long keel , heavy displacement and high bulwarks, it was intended to evoke the spirit of North Sea fishing boats.

It might not sail brilliantly but it provided an exceptional level of comfort for its size and it would look after you when things turned nasty.

Significantly, it was also fitted with a large engine.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

It should have been a disaster.

In 1941, when the Scandinavian Sailing Federation couldn’t choose a winner for their competition to design an affordable sailing boat, they gave six designs to naval architect Tord Sundén and asked him to combine the best features from each.

The result was a sweet-lined 25ft sloop which was very seaworthy and fast.

The design has been built in GRP since the 1970s and now numbers more than 4,000, with fleets all over the world.

Credit: Kevin Barber

There’s something disconcerting about a boat with two unstayed masts and no foresails, and certainly the Freedom range has its detractors.

Yet as Garry Hoyt proved, first with the Freedom 40, designed in collaboration with Halsey Herreshoff, and then the Freedom 33 , designed with Jay Paris, the boats are simple to sail (none of those clattering jib sheets every time you tack) and surprisingly fast – at least off the wind .

Other ‘cat ketch’ designs followed but the Freedoms developed their own cult following.

Hillyard 12-tonner

The old joke about Hillyards is that you won’t drown on one but you might starve to death getting there.

And yet this religious boatbuilder from Littlehampton built up to 800 yachts which travelled around the world – you can find them cruising far-flung destinations.

Sizes ranged from 2.5 to 20 tons, though the 9- and 12-ton are best for long cruises.

The innovations on Jester means she is one of the best small sailing boat designs in the last 100 years. Credit: Ewen Southby-Tailyour

Blondie Hasler was one of the great sailing innovators and Jester was his testing ground.

She was enclosed, carvel planked and had an unstayed junk rig.

Steering was via a windvane system Hasler created.

Hasler came second in the first OSTAR , proving small boats can achieve great things.

Moody kicked off the era of comfort-oriented boats with its very first design.

The Moody 33, designed by Angus Primrose, had a wide beam and high topside to produce a voluminous hull .

The centre cockpit allowed for an aft cabin, resulting in a 33-footer with two sleeping cabins – an almost unheard of concept in 1973 –full-beam heads and spacious galley.

What’s more, her performance under sail was more than adequate for cruising.

Finally, here was a yacht that all the family could enjoy.

Continues below…

What makes a boat seaworthy?

What characteristics make a yacht fit for purpose? Duncan Kent explores the meaning of 'seaworthy' and how hull design and…

How boat design is evolving

Will Bruton looks at the latest trends and innovations shaping the boats we sail

How keel type affects performance

James Jermain looks at the main keel types, their typical performance and the pros and cons of each

Boat handling: How to use your yacht’s hull shape to your advantage

Whether you have a long keel or twin keel rudders, there will be pros and cons when it comes to…

Nicholson 32

Credit: Genevieve Leaper

Charles Nicholson was a giant of the wooden boat era but one of his last designs – created with his son Peter – was a pioneering fibreglass boat that would become an enduring classic.

With its long keel and heavy displacement, the Nicholson 32 is in many ways a wooden boat built in fibreglass – and indeed the design was based on Nicholson’s South Coast One Design.

From 1966 to 1977, the ‘Nic 32’ went through 11 variations.

Credit: Hallberg-Rassy

In the beginning there was… the Rasmus 35. This was the first yacht built by the company that would become Hallberg-Rassy and which would eventually build more than 9,000 boats.

The Rasmus 35, designed by Olle Enderlein, was a conservative design, featuring a centre cockpit, long keel and well-appointed accommodation.

Some 760 boats were built between 1967 and 1978.

Credit: Larry & Lin Pardey

Lyle Hess was ahead of his time when he designed Renegade in 1949.

Despite winning the Newport to Ensenada race, the 25ft wooden cutter went largely unnoticed.

Hess had to build bridges for 15 years before Larry Pardey asked him to design the 24ft Seraffyn , closely based on Renegade ’s lines but with a Bermudan rig.

Pardey’s subsequent voyages around the world cemented Hess’s reputation and success of the Renegade design.

Would the Rustler 36 make it on your best small sailing boat list? Credit: Rustler Yachts

Six out of 18 entries for the 2018 Golden Globe Race (GGR) were Rustler 36s, with the top three places all going to Rustler 36 skippers.

It was a fantastic endorsement for a long-keel yacht designed by Holman & Pye 40 years before.

Expect to see more Rustler 36s in the 2022 edition of the GGR!

It was Ted Heath who first brought the S&S 34 to prominence with his boat Morning Cloud .

In 1969 the yacht won the Sydney to Hobart Race, despite being one of the smallest boats in the race.

Other epic S&S 34 voyages include the first ever single-handed double circumnavigation by Jon Sanders in 1981

Credit: Colin Work

The Contessa 32 might seem an impossible boat to improve upon, but that’s what her designer David Sadler attempted to do in 1979 with the launch of the Sadler 32 .

That was followed two years later by the Sadler 29 , a tidy little boat that managed to pack in six berths in a comfortable open-plan interior.

The boat was billed as ‘unsinkable’, with a double-skinned hull separated by closed cell foam buoyancy.

What’s more, it was fast, notching up to 12 knots.

Credit: Dick Durham/Yachting Monthly

Another modern take on the Contessa theme was the Sigma 33, designed by David Thomas in 1979.

A modern underwater body combined with greater beam and higher freeboard produced a faster boat with greater accommodation.

And, like the Contessa, the Sigma 33 earned its stripes at the 1979 Fastnet, when two of the boats survived to tell the tale.

A lively one-design fleet soon developed on the Solent which is still active to this day.

A replica of Joshua Slocum’s Spray . Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

The boat Joshua Slocum used for his first singlehanded circumnavigation of the world wasn’t intended to sail much further than the Chesapeake Bay.

The 37ft Spray was a rotten old oyster sloop which a friend gave him and which he had to spend 13 months fixing up.

Yet this boxy little tub, with its over-optimistic clipper bow, not only took Slocum safely around the world but has spawned dozens of modern copies that have undertaken long ocean passages.

Credit: James Wharram Designs

What are boats for if not for dreaming? And James Wharram had big dreams.

First he sailed across the Atlantic on the 23ft 6in catamaran Tangaroa .

He then built the 40ft Rongo on the beach in Trinidad (with a little help from French legend Bernard Moitessier) and sailed back to the UK.

Then he drew the 34ft Tangaroa (based on Rongo ) for others to follow in his wake and sold 500 plans in 10 years.

Credit: Graham Snook/Yachting Monthly

The Twister was designed in a hurry.

Kim Holman wanted a boat at short notice for the 1963 season and, having had some success with his Stella design (based on the Folkboat), he rushed out a ‘knockabout cruising boat for the summer with some racing for fun’.

The result was a Bermudan sloop that proved nigh on unbeatable on the East Anglian circuit.

It proved to be Holman’s most popular design with more than 200 built.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Laurent Giles’s design No15 was drawn in 1935 for a Guernsey solicitor who wanted ‘a boat that would spin on a sixpence and I could sail single-handed ’.

What the young Jack Giles gave him was a pretty transom-sterned cutter, with a nicely raked stem.

Despite being moderate in every way, the boat proved extremely able and was soon racking up long distances, including Humphrey Barton’s famous transatlantic crossing on Vertue XXXV in 1950.

Wanderer II and III

Credit: Thies Matzen

Eric and Susan Hiscock couldn’t afford a Vertue, so Laurent Giles designed a smaller, 21ft version for them which they named Wanderer II .

They were back a few years later, this time wanting a bigger version: the 30ft Wanderer III .

It was this boat they sailed around the world between 1952-55, writing articles and sailing books along the way.

In doing so, they introduced a whole generation of amateur sailors to the possibilities of long-distance cruising.

Westerly 22

The origins of Westerly Marine were incredibly modest.

Commander Denys Rayner started building plywood dinghies in the 1950s which morphed into a 22ft pocket cruiser called the Westcoaster.

Realising the potential of fibreglass, in 1963 he adapted the design to create the Westerly 22, an affordable cruising boat with bilge keels and a reverse sheer coachroof.

Some 332 boats were built to the design before it was relaunched as the Nomad (267 built).

Enjoyed reading 25 of the best small sailing boat designs?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price .

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals .

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram.

My Cruiser Life Magazine

Basics of Sailboat Hull Design – EXPLAINED For Owners

There are a lot of different sailboats in the world. In fact, they’ve been making sailboats for thousands of years. And over that time, mankind and naval architects (okay, mostly the naval architects!) have learned a thing or two.

If you’re wondering what makes one sailboat different from another, consider this article a primer. It certainly doesn’t contain everything you’d need to know to build a sailboat, but it gives the novice boater some ideas of what goes on behind the curtain. It will also provide some tips to help you compare different boats on the water, and hopefully, it will guide you towards the sort of boat you could call home one day.

Table of Contents

Displacement hulls, semi displacement hulls, planing hulls, history of sailboat hull design, greater waterline length, distinctive hull shape and fin keel designs, ratios in hull design, the hull truth and nothing but the truth, sail boat hull design faqs.

Basics of Hull Design

When you think about a sailboat hull and how it is built, you might start thinking about the shape of a keel. This has certainly spurred a lot of different designs over the years, but the hull of a sailboat today is designed almost independently of the keel.

In fact, if you look at a particular make and model of sailboat, you’ll notice that the makers often offer it with a variety of keel options. For example, this new Jeanneau Sun Odyssey comes with either a full fin bulb keel, shallow draft bulb fin, or very shallow draft swing keel. Where older long keel designs had the keel included in the hull mold, today’s bolt-on fin keel designs allow the manufacturers more leeway in customizing a yacht to your specifications.

What you’re left with is a hull, and boat hulls take three basic forms.

- Displacement hull

- Semi-displacement hulls

- Planing hulls

Most times, the hull of a sailboat will be a displacement hull. To float, a boat must displace a volume of water equal in weight to that of the yacht. This is Archimedes Principle , and it’s how displacement hulled boats get their name.

The displacement hull sailboat has dominated the Maritimes for thousands of years. It has only been in the last century that other designs have caught on, thanks to advances in engine technologies. In short, sailboats and sail-powered ships are nearly always displacement cruisers because they lack the power to do anything else.

A displacement hull rides low in the water and continuously displaces its weight in water. That means that all of that water must be pushed out of the vessel’s way, and this creates some operating limitations. As it pushes the water, water is built up ahead of the boat in a bow wave. This wave creates a trough along the side of the boat, and the wave goes up again at the stern. The distance between the two waves is a limiting factor because the wave trough between them creates a suction.

This suction pulls the boat down and creates drag as the vessel moves through the water. So in effect, no matter how much power is applied to a displacement hulled vessel, it cannot go faster than a certain speed. That speed is referred to as the hull speed, and it’s a factor of a boat’s length and width.

For an average 38 foot sailboat, the hull speed is around 8.3 knots. This is why shipping companies competed to have the fastest ship for many years by building larger and larger ships.

While they might sound old-school and boring, displacement hulls are very efficient because they require very little power—and therefore very little fuel—to get them up to hull speed. This is one reason enormous container ships operate so efficiently.

Of course, living in the 21st century, you undoubtedly have seen boats go faster than their hull speed. Going faster is simply a matter of defeating the bow wave in one way or another.

One way is to build the boat so that it can step up onto and ride the bow wave like a surfer. This is basically what a semi-displacement hull does. With enough power, this type of boat can surf its bow wave, break the suction it creates and beat its displacement hull speed.

With even more power, a boat can leave its bow wave in the dust and zoom past it. This requires the boat’s bottom to channel water away and sit on the surface. Once it is out of the water, any speed is achievable with enough power.

But it takes enormous amounts of power to get a boat on plane, so planing hulls are hardly efficient. But they are fast. Speedboats are planing hulls, so if you require speed, go ahead and research the cost of a speedboat .

The most stable and forgiving planing hull designs have a deep v hull. A very shallow draft, flat bottomed boat can plane too, but it provides an unforgiving and rough ride in any sort of chop.

If you compare the shapes of the sailboats of today with the cruising boat designs of the 1960s and 70s, you’ll notice that quite a lot has changed in the last 50-plus years. Of course, the old designs are still popular among sailors, but it’s not easy to find a boat like that being built today.

Today’s boats are sleeker. They have wide transoms and flat bottoms. They’re more likely to support fin keels and spade rudders. Rigs have also changed, with the fractional sloop being the preferred setup for most modern production boats.

Why have boats changed so much? And why did boats look so different back then?

One reason was the racing standards of the day. Boats in the 1960s were built to the IOR (International Offshore Rule). Since many owners raced their boats, the IOR handicaps standardized things to make fair play between different makes and models on the racecourse.

The IOR rule book was dense and complicated. But as manufacturers started building yachts, or as they looked at the competition and tried to do better, they all took a basic form. The IOR rule wasn’t the only one around . There were also the Universal Rule, International Rule, Yacht Racing Association Rul, Bermuda Rule, and a slew of others.

Part of this similarity was the rule, and part of it was simply the collective knowledge and tradition of yacht building. But at that time, there was much less distance between the yachts you could buy from the manufacturers and those setting off on long-distance races.

Today, those wishing to compete in serious racing a building boat’s purpose-built for the task. As a result, one-design racing is now more popular. And similarly, pleasure boats designed for leisurely coastal and offshore hops are likewise built for the task at hand. No longer are the lines blurred between the two, and no longer are one set of sailors “making do” with the requirements set by the other set.

Modern Features of Sailboat Hull Design

So, what exactly sets today’s cruising and liveaboard boats apart from those built-in decades past?

Today’s designs usually feature plumb bows and the maximum beam carried to the aft end. The broad transom allows for a walk-through swim platform and sometimes even storage for the dinghy in a “garage.”

The other significant advantage of this layout is that it maximizes waterline length, which makes a faster boat. Unfortunately, while the boats of yesteryear might have had lovely graceful overhangs, their waterline lengths are generally no match for newer boats.

The wide beam carried aft also provides an enormous amount of living space. The surface area of modern cockpits is nothing short of astounding when it comes to living and entertaining.

If you look at the hull lines or can catch a glimpse of these boats out of the water, you’ll notice their underwater profiles are radically different too. It’s hard to find a full keel design boat today. Instead, fin keels dominate, along with high aspect ratio spade rudders.

The flat bottom boats of today mean a more stable boat that rides flatter. These boats can really move without heeling over like past designs. Additionally, their designs make it possible in some cases for these boats to surf their bow waves, meaning that with enough power, they can easily achieve and sometimes exceed—at least for short bursts—their hull speeds. Many of these features have been found on race boats for decades.

There are downsides to these designs, of course. The flat bottom boats often tend to pound when sailing upwind , but most sailors like the extra speed when heading downwind.

How Do You Make a Stable Hull

Ultimately, the job of a sailboat hull is to keep the boat afloat and create stability. These are the fundamentals of a seaworthy vessel.

There are two types of stability that a design addresses . The first is the initial stability, which is how resistant to heeling the design is. For example, compare a classic, narrow-beamed monohull and a wide catamaran for a moment. The monohull has very little initial stability because it heels over in even light winds. That doesn’t mean it tips over, but it is relatively easy to make heel.

A catamaran, on the other hand, has very high initial stability. It resists the heel and remains level. Designers call this type of stability form stability.

There is also secondary stability, or ultimate stability. This is how resistant the boat is to a total capsize. Monohull sailboats have an immense amount of ballast low in their keels, which means they have very high ultimate stability. A narrow monohull has low form stability but very high ultimate stability. A sailor would likely describe this boat as “tender,” but they would never doubt its ability to right itself after a knock-down or capsize.

On the other hand, the catamaran has extremely high form stability, but once the boat heels, it has little ultimate stability. In other words, beyond a certain point, there is nothing to prevent it from capsizing.

Both catamarans and modern monohulls’ hull shapes use their beams to reduce the amount of ballast and weight . A lighter boat can sail fast, but to make it more stable, naval architects increase the beam to increase the form stability.

If you’d like to know more about how stable a hull is, you’ll want to learn about the Gz Curve , which is the mathematical calculation you can make based on a hull’s form and ultimate stabilities.

How does a lowly sailor make heads or tails out of this? You don’t have to be a naval architect when comparing different designs to understand the basics. Two ratios can help you predict how stable a design will be .

The first is the displacement to length ratio . The formula to calculate it is D / (0.01L)^3 , where D is displacement in tons and L is waterline length in feet. But most sailboat specifications, like those found on sailboatdata.com , list the D/L Ratio.

This ratio helps understand how heavy a boat is for its length. Heavier boats must move more water to make way, so a heavy boat is more likely to be slower. But, for the ocean-going cruiser, a heavy boat means a stable boat that requires much force to jostle or toss about. A light displacement boat might pound in a seaway, and a heavy one is likely to provide a softer ride.

The second ratio of interest is the sail area to displacement ratio. To calculate, take SA / (D)^0.67 , where SA is the sail area in square feet and D is displacement in cubic feet. Again, many online sites provide the ratio calculated for specific makes and models.

This ratio tells you how much power a boat has. A lower ratio means that the boat doesn’t have much power to move its weight, while a bigger number means it has more “get up and go.” Of course, if you really want to sail fast, you’d want the boat to have a low displacement/length and a high sail area/displacement.

Multihull Sailboat Hulls

Multihull sailboats are more popular than ever before. While many people quote catamaran speed as their primary interest, the fact is that multihulls have a lot to offer cruising and traveling boaters. These vessels are not limited to coastal cruising, as was once believed. Most sizable cats and trimarans are ocean certified.

Both catamarans and trimaran hull designs allow for fast sailing. Their wide beam allows them to sail flat while having extreme form stability.

Catamarans have two hulls connected by a large bridge deck. The best part for cruisers is that their big surface area is full of living space. The bridge deck usually features large, open cockpits with connecting salons. Wrap around windows let in tons of light and fresh air.

Trimarans are basically monohulls with an outrigger hull on each side. Their designs are generally less spacious than catamarans, but they sail even faster. In addition, the outer hulls eliminate the need for heavy ballast, significantly reducing the wetted area of the hulls.

Boaters and cruising sailors don’t need to be experts in yacht design, but having a rough understanding of the basics can help you pick the right boat. Boat design is a series of compromises, and knowing the ones that designers and builders take will help you understand what the boat is for and how it should be used.

What is the most efficient boat hull design?

The most efficient hull design is the displacement hull. This type of boat sits low in the water and pushes the water out of its way. It is limited to its designed hull speed, a factor of its length. But cruising at hull speed or less requires very little energy and can be done very efficiently.

By way of example, most sailboats have very small engines. A typical 40-foot sailboat has a 50 horsepower motor that burns around one gallon of diesel every hour. In contrast, a 40-foot planing speedboat may have 1,000 horsepower (or more). Its multiple motors would likely be consuming more than 100 gallons per hour (or more). Using these rough numbers, the sailboat achieves about 8 miles per gallon, while the speedboat gets around 2 mpg.

What are sail boat hulls made of?

Nearly all modern sailboats are made of fiberglass.

Traditionally, boats were made of wood, and many traditional vessels still are today. There are also metal boats made of steel or aluminum, but these designs are less common. Metal boats are more common in expedition yachts or those used in high-latitude sailing.

Matt has been boating around Florida for over 25 years in everything from small powerboats to large cruising catamarans. He currently lives aboard a 38-foot Cabo Rico sailboat with his wife Lucy and adventure dog Chelsea. Together, they cruise between winters in The Bahamas and summers in the Chesapeake Bay.

- Types of Sailboats

- Parts of a Sailboat

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

Sailboat Design: Stability, Buoyancy and Performance

Simply stated, the first requirement of sailboat design is that the yacht designer's creation is seaworthy; particularly in that it stays afloat and is highly resistant to capsize - but of course we expect rather more than that...

Good sailing performance, particularly to windward, will be high on the list of most sailors' requirements. As will the availability of sufficient space below decks to accommodate the crew and the stores, and all the other sailing paraphernalia.

And the boat must be easy to handle, both under sail at sea and under power in the marina. It must be comfortable, for it's not always just a sailing machine - at times it has to function as a home too.

So a design that successfully incorporates all these requirements won't just happen by accident - but however accomplished your yacht designer, you'll not be able to have everything...

We sailors recognise the stability element of sailboat design as the difference between a 'stiff' boat and a 'tender' one. And whether it's one or the other depends on the relationship between the righting moment applied by the hull and the heeling moment applied by the wind-loaded sails.

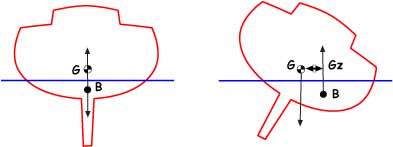

As can be seen in the sketch, the righting moment (Gz) is the horizontal distance between the boat's Centre of Gravity (G) and its Centre of Buoyancy (B).

The righting moment increases as the boat heels until a point is reached at which the heeling moment becomes equal to the righting moment, following which any further increase in heeling moment will cause the boat to capsize.

This is best expressed graphically by way of a Gz Curve, which plots Righting Moment against Heel Angle.

This curve establishes the Angle of Vanishing Stability , effectively the point of no return for a sailboat about to capsize, and which is a major factor in allocating any sailboat to one of the four recognised sailboat design categories - Ocean, Offshore, Inland and Sheltered Waters .

If you're planning to buy or charter a sailboat, you should always check its Design Category to make sure that it's suitable for your purposes.

Displacement, Freeboard and the Centre of Gravity