Please enter at least 3 characters

“John Ford’s Navy”: A Filmmaker in the OSS

Hollywood director John Ford brought unique fallen to the film interpretation of World War II.

This article appears in: April 2014

By Michael D. Hull

With such award-winning films as Stagecoach , Young Mr. Lincoln , Drums Along the Mohawk , The Grapes of Wrath , The Long Voyage Home , and How Green Was My Valley behind him, John Ford was one of Hollywood’s most respected directors by the time World War II broke out in 1939.

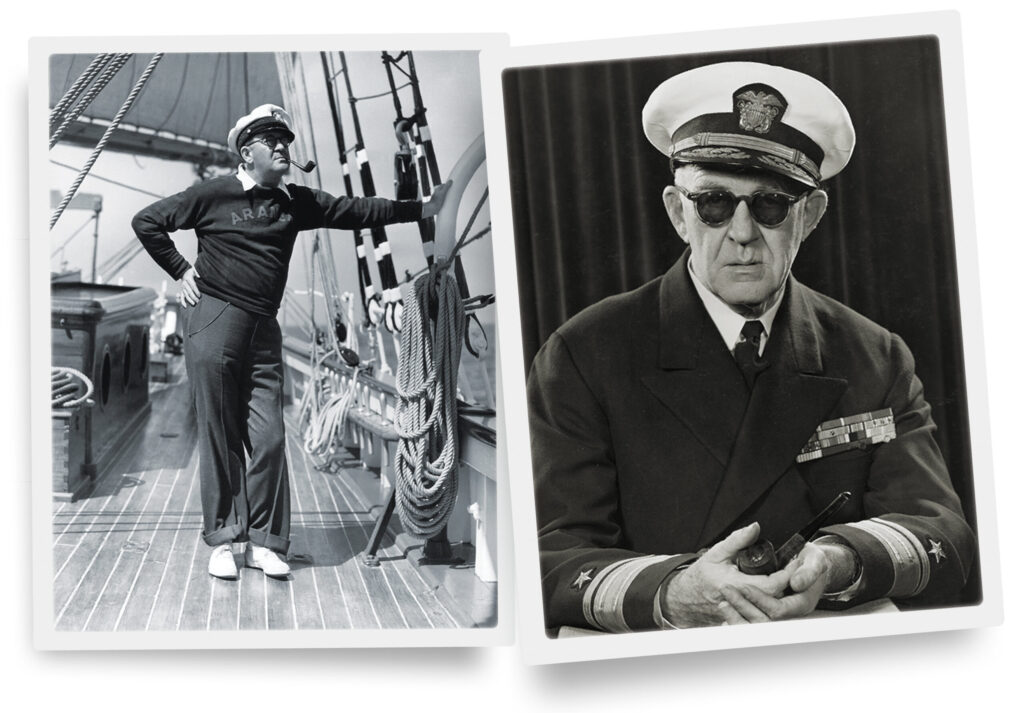

But 46-year-old Ford, the owner of the Araner, a 110-foot, two-masted yacht, also dreamed of becoming a naval hero, although he had failed the entrance examination for the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1914. He was sure that his country would be drawn into the conflict, offering him his “last chance to be a boy.” He started his naval service several years before the Pearl Harbor attack sent America to war.

After being appointed a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Naval Reserve in September 1934, Ford made periodic cruises aboard his yacht down the coast of Baja California between 1936 and 1939, gathering information for the 11th Naval District. He reported that the crews of Japanese shrimp boats off the Mexican coast were spying and constituting “a real menace” to national defense. He said that there were Imperial Navy officers aboard the trawlers and that the Japanese were familiar with every cove and inlet of the Gulf of California. Ford was commended for his “unselfish and patriotic work.”

John Ford’s Navy

By the autumn of 1939, with Europe now engulfed in war, Ford’s desire to get involved intensified. Garnering a second Academy Award for his Dust Bowl saga The Grapes of Wrath did not deter him. “Awards for pictures are a trivial thing to be concerned with at times like these,” he explained. So, in April 1940, Ford created an unofficial Naval Reserve unit.

His recruits for the Naval Field Photographic Unit, known simply as Field Photographic, were some of the best talents in Hollywood. They included writers Garson Kanin and Budd Schulberg, cinematographer Gregg Toland, editor Robert Parrish, and special effects expert Ray Kellogg. The unit’s mission was to photograph combat, and Ford hoped that the Navy Department would recognize the value of such a trained auxiliary.

Aided by retired chief petty officer and actor Jack Pennick, a gaunt Marine Corps veteran of World War I and China service, Ford molded the ragtag group into a military force. Its members wore rented uniforms, carried weapons borrowed from the 20th Century-Fox property department, and drilled on a studio soundstage. They learned discipline and even sword drill because “Pappy” Ford, while hating regulations, loved military ceremony. The group became known as “John Ford’s Navy.”

Accepting Field Photographic Into the OSS

The project was not taken seriously by the Navy brass for some months. Ford was ridiculed in some quarters as a “warmonger” and an “over-age Sea Scout,” and his appeals for authorization drew no response. But he was well connected in the Naval Reserve, and he persisted. He lobbied in Washington, and his unit eventually gained official sanction late in 1940. By 1941, with the draft being felt in Hollywood, Field Photographic was deluged with applications.

In September 1941, Ford and his unit members were summoned to Washington where a big surprise awaited them. With the support of Merian C. Cooper, a film producer and colorful soldier of fortune, Field Photographic had been accepted intact—not by the Navy but by the newly formed Office of Strategic Services headed by Colonel William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, a legendary World War I Medal of Honor winner. Ford was to be accountable to Donovan, who in turn reported to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The unit was assigned an operating budget of $5 million for its first year.

Ford’s unit received its first assignment in November 1941, when Donovan ordered it to produce a filmed report on the U.S. Atlantic Fleet as it helped the British escort convoys and waged an undeclared war against German U-boats. Donovan showed the film to Roosevelt. Shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack, Field Photographic was sent south to film defenses in the Panama Canal Zone.

In February 1942, Ford turned over his yacht to the Navy for use as a patrol craft off the California coast. Many Hollywood luminaries, meanwhile, joined the war effort. Ford’s attractive, elegant wife, Mary, worked at the popular Hollywood Canteen, and his stars John Wayne and Ward Bond served as air raid wardens in Los Angeles.

The Doolittle Raid

Impressed with Ford’s North Atlantic and Panama documentaries, Colonel Donovan—backed by FDR—next ordered Field Photographic to film the war in the Pacific, beginning with a top secret report on the Pearl Harbor debacle. The unit started filming in Hawaii, and Ford flew to Honolulu in mid-February to check on progress. While there, he learned of a planned raid against Japan by Colonel James H. Doolittle’s Army Air Forces North American B-25 Mitchell medium bombers from the carrier USS Hornet . Leaving Toland in charge of the Pearl Harbor film project, Ford and several cameramen managed to talk their way into joining Vice Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr.’s Task Force 16, formed around the Hornet , so that they could cover the launching.

Ford sailed aboard the heavy cruiser USS Salt Lake City . On the morning of April 14, 1942, four days before Doolittle’s 16 bombers lifted off the Hornet, Ford was proud to learn from the cruiser’s radio that he had won his third Academy Award for How Green Was My Valley , the poignant story of a Welsh coal mining family.

But the irascible, hard-drinking filmmaker, who liked to be called Jack, was angered when he returned to Hawaii and learned that the Navy had confiscated Toland’s Pearl Harbor film and locked it in a vault because it was considered controversial. The high-strung, depressed Toland was assigned to the Field Photographic station in Rio de Janeiro, and Ford headed for Washington.

Field Photographic Goes to Midway

During a brief stay in the hot, muggy capital, Ford was told by Donovan that something big was imminent in the Pacific. Navy cryptographers had breached Japanese codes and learned that the Imperial Navy was trying to provoke the U.S. Pacific Fleet, still weak after the Pearl Harbor attack, into a confrontation around remote Midway Atoll, 1,304 nautical miles northwest of Hawaii. Donovan asked Ford to fly out and film what might be the most important naval battle of the Pacific War.

The filmmaker did not hesitate. In mid-May, he flew in a Douglas C-47 transport to San Francisco and boarded a destroyer for his four-day return to Pearl Harbor. Then, Ford and Jack MacKenzie, a photographer’s mate, rode a Navy patrol plane to Midway. Circling the tiny atoll after a four-hour flight, Ford peered down and saw that its small Marine and Navy garrison was braced for action. Sandbags were piled, slit trenches dug, machine guns positioned, and ground crews bustled around fighter planes on the airstrip.

Ford sensed the resolve of Midway’s defenders and was in high spirits. “This is some place, really fascinating,” he wrote to his wife on June 1. “The morale here is extremely high, and the food is really delicious—best I’ve had in the Navy.”

When a Midway-based patrol bomber sighted the powerful Japanese fleet on the morning of June 3, 1942, Midway’s Marine battalion and sailors took last minute defense measures. As more emplacements were hastily dug, fighters fueled, and ammunition belts distributed, Ford and MacKenzie got ready to film the inevitable attack.

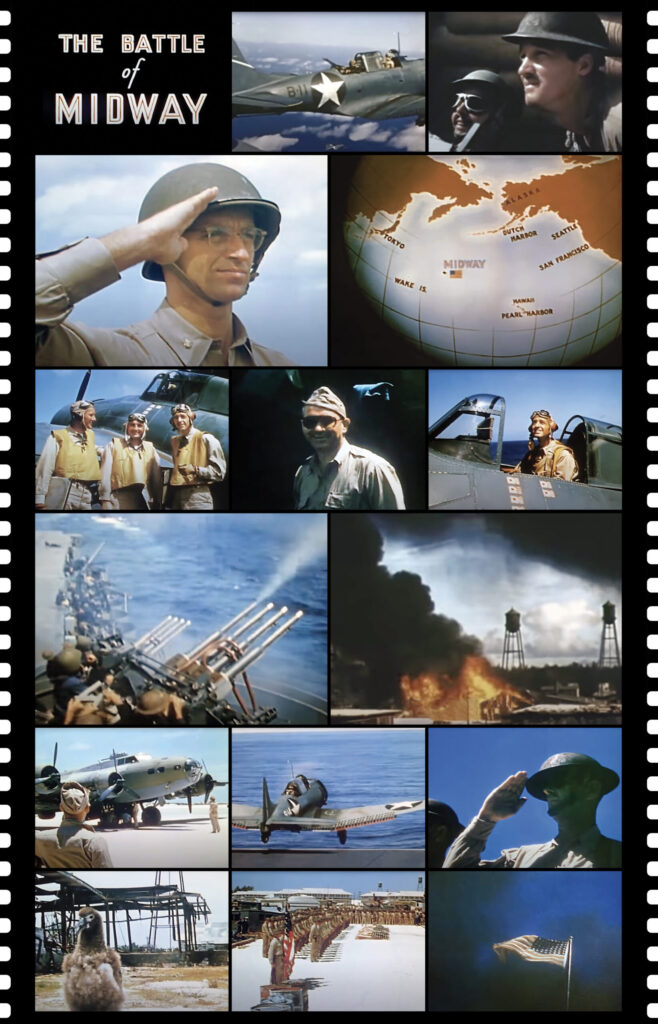

Filming the Battle of Midway

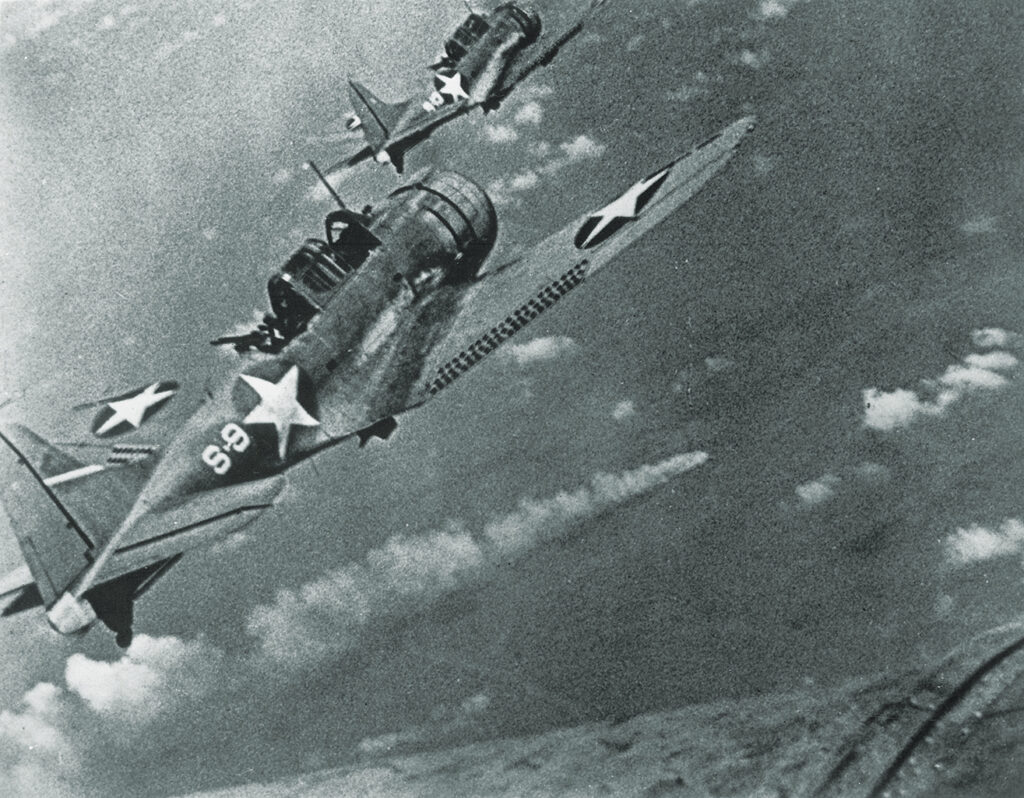

On Thursday, June 4, the two-day Battle of Midway —the most decisive naval engagement since Trafalgar—began as dive bombers and torpedo bombers from the U.S. carriers Hornet, Enterprise, and Yorktown, led by Rear Admirals Frank Jack Fletcher and Raymond A. Spruance, sought out and attacked Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s four carriers, Akagi , Kaga , Soryu , and Hiryu .

On Midway itself, Pappy Ford and the red haired, freckled MacKenzie took their positions with hand cameras and waited tensely. Ford climbed the airfield’s wooden control tower and sent MacKenzie to Midway’s generating plant. Ford advised the young man, “Photograph faces. We can always fake combat footage later.” They did not have long to wait.

At dawn on June 4, before Ford had dressed, Midway came under attack. Waves of Japanese carrier bombers and fighters roared in, bombing and strafing. Explosions shook the atoll, debris flew, and a fuel dump belched smoke and flame. Though feverish and with their hearts pounding, Ford and MacKenzie calmly captured on film the fury around them—incoming enemy planes, bombs falling, fires, leathernecks firing machine guns, weary American fighter pilots returning, medical corpsmen carrying bodies to ambulances, and smoking wreckage.

On the control tower, Ford was both terrified and exhilarated when Japanese fighters zoomed in and riddled the structure. One of the planes came so close that Ford saw the pilot give him a toothy grin. At 8 that morning, the filmmaker aimed his camera at a group of Marines hoisting the Stars and Stripes while smoke and flame swirled in the background. The dramatic shot eventually became one of the best known images of World War II.

As Ford descended from the control tower, a close hit by an enemy plane stunned him. Then he realized that he was bleeding. Shrapnel had splintered his left forearm. He sought medical attention and then continued to film the attack and devastation. The filmmaker was later awarded the Purple Heart and a citation from the 14th Naval District recognizing his “courage and devotion to duty.”

In the close-run naval battle, meanwhile, American carrier planes had sunk the four enemy flattops and scored a costly but momentous victory. Yamamoto abandoned Midway invasion plans, and his shattered fleet retired westward. The Imperial Navy had been put on the defensive in the Pacific.

“Hollywood’s Own Personal Hero”

Ford spent several days photographing Midway’s damage before quietly collecting his footage—eight cans of color film—and sailing to Los Angeles aboard a transport ship. He had a rush print made of the Midway film and found himself being hailed as a combat hero. A Hollywood Reporter headline announced on June 18, “Ford Filmed Battle of Midway,” while columnist Louella Parsons gushed that he “is Hollywood’s own personal hero.”

The filmmaker flew on to Washington and arrived at OSS headquarters unshaven and with his left arm bandaged. He went to work immediately on the Midway footage with editor Parrish. Ford wanted no official interference and suspected that Navy brass and censors might come “snooping around,” so he ordered Parrish to fly to Hollywood and work on the film there.

Parrish assembled the film on the 20th Century-Fox lot. Screenwriter Dudley Nichols wrote a narration, which was rewritten by Jim McGuinness of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Ford flew out when the project was ready. The narration was recorded by Henry Fonda, Jane Darwell, and Donald Crisp, three of Ford’s players, and the director watched a screening of the rough cut in a locked editing room while a Marine stood watch outside. Ford regarded the 18-minute documentary, titled The Battle of Midway, as a timely morale booster. “It’s for the mothers of America,” he declared. “It’s to let them know that we’re in a war and that we’ve been getting the s—- kicked out of us for five months, and now we’re starting to hit back.”

Donovan and the director rushed the film to the White House, where it was promptly viewed by the president, his wife, Eleanor, trusted adviser Harry L. Hopkins, and Admiral William D. Leahy, FDR’s senior naval aide. The footage included a shot of Marine Corps Major James Roosevelt attending a memorial service for the Midway dead, and when the president recognized his son, he fell silent. After the viewing, the first lady wept and FDR was ashen. Turning to Leahy, the president said, “I want every mother in America to see this picture.”

Twentieth Century-Fox distributed 500 prints to theaters across the country, and the first public screening was at New York’s Radio City Music Hall on September 14, 1942. Editor Parrish reported, “It was a stunning, amazing thing to see.… City women screamed, people cried, and the ushers had to take them out.… The people, they just went crazy.”

Ahead of its time, the Ford film was propagandist yet realistic and inspirational and showed that an Allied victory in the Pacific was possible. The Battle of Midway was widely seen and critically acclaimed and eventually won the Academy Award for best documentary short subject of 1942.

Cameras Rolling on Operation Torch

Immediately after the White House screening, Ford flew to London in a Pan American flying boat with Pennick, now his unofficial aide. The purpose was to organize Field Photographic crews for Operation Torch, the upcoming Allied invasion of North Africa. Ford sent his camera crews to the British Commando School at Achnacarry in the Scottish Highlands for special training and conditioning.

The complex invasion was launched on November 8, 1942, with three Allied task forces converging on the Morocco-Algeria coasts. Thirty-four thousand U.S. troops landed near Casablanca; 39,000 British and U.S. troops went ashore near Oran, supported by airborne troops; and 33,000 men landed near Algiers. Pappy Ford waited in Gibraltar, impatient to get to the front.

As soon as permission was granted, he left Gibraltar on November 14 with Pennick and photographer’s mate Robert Johannes. They commandeered a jeep in Algiers and attached themselves to D Company of the 13th Armored Regiment in Major General Orlando Ward’s 1st Armored Division. The regiment advanced to the Algerian port of Bone, where Ford spent several days with Hollywood producer Darryl F. Zanuck. Driving a requisitioned Chevrolet coupe and armed with a Tommy gun, two pistols, and hand grenades, the diminutive Zanuck was covering the war for a documentary and a book.

Ford and his 32 cameramen saw plenty of action in Algeria and Tunisia. Huddling in foxholes and sharing the risks and hardships of the tankers and infantrymen, they survived German artillery, machine-gun fire, and dive bombers. Ford lost 32 pounds while subsisting on tea and hard English biscuits.

Capturing a German Pilot

One day in Tunisia, while D Company was under attack by German bombers and dive bombers, Ford, Pennick, and Johannes took refuge in a grove of eucalyptus trees. A flight of Royal Air Force Supermarine Spitfires swooped to attack the enemy planes, and Ford had his camera ready to film the fierce dogfight that ensued. He watched a Spitfire shoot down a twin-engine Junkers Ju-88 medium bomber, and a crewman bailed out.

As the parachute billowed and drifted down, Ford shouted to his companions, “Come on! Let’s take him prisoner.” The three Americans jumped into their jeep and careened across wadis and scrubland to where the German had landed. He surrendered, told Ford that he was the bombardier, and asked to be taken to where the plane had crashed to see if any others of the four-man crew had survived. Ford agreed.

But the smoking wreckage yielded three charred bodies. While the bombardier mourned his friends and Ford pondered what to do with him, a Free French Army lieutenant drove up and demanded jurisdiction over the German. Ford turned him over, and the Frenchman began slapping the captive while interrogating him. Ford intervened, saying, “OK, that’s enough! The prisoner stays with us.” The French officer was enraged, but Ford stood his ground and eventually turned over the airman to the company commander. The German was not aware that the humane American who had captured him was a famous Hollywood director.

December 7th

After their six hectic weeks in combat, Ford, Pennick, and Johannes flew to Gibraltar in December 1942, and then headed home aboard the attack transport USS Samuel Chase . Ford, who had been promoted to captain in the U.S. Naval Reserve, then spent several months in Washington busying himself with his film unit and lobbying high-ranking officers and Congressmen. But he grew bored, so he decided to resurrect footage of the Pearl Harbor disaster by Toland and Navy cameramen. Parrish trimmed the footage to half an hour, Budd Schulberg wrote the narration, and Alfred Newman, one of Hollywood’s leading composers, wrote the score. The documentary was titled December 7th .

As part of the Industrial Incentives Program, the film was not released to theaters, but was shown in defense plants to boost production and morale. Producer Walter Wanger told its director that December 7th was a “great picture” and a “triumph,” and it received an Academy Award for best documentary of 1943.

Ford in the CBI Theater

Ford continued globetrotting and his association with Colonel Donovan. In the summer of 1943, while the latter was getting the OSS established in the China-Burma-India Theater, the tireless filmmaker flew to New Delhi to oversee work on a new documentary, Victory in Burma. The film would focus on the theater commander, Lord Louis Mountbatten, and the long, bitter struggle waged against the Japanese in the Burmese jungles by General William Slim’s “forgotten” British 14th Army. Ford flew reconnaissance flights to China, photographed air raids in Burma and China, and worked closely with Maj. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, the theater commander of U.S. forces, and Maj. Gen. Claire L. Chennault , leader of the U.S. Fourteenth Air Force and the legendary Flying Tigers.

After a wearying seven-day flight from New Delhi, Ford and Pennick arrived home in January 1944. Called into Donovan’s office, Ford was praised for his efforts in the Far East, told that he had been a great asset to the OSS, and was recommended for promotion to captain. Donovan then informed him that his Field Photographic would be in charge of filming the planned Allied invasion of Normandy. The filmmaker was both stunned and jubilant.

John Ford Meets John Bulkeley

Captain Ford flew to England early in April 1944 and busied himself for the next two months getting his film unit ready to cover the invasion. Mark Armistead’s Field Photographic team in London had been hard at work for 18 months photographing the European coast from low-flying B-25 bombers and gathering data on French waters, beaches, and inland terrain. One of Armistead’s prime sources on the Normandy shore was his friend, Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley, the commander of a PT-boat squadron in the English Channel.

“Buck” Bulkeley had gained fame as a daring PT-boat skipper in the doomed Philippines early in 1942 and for evacuating General Douglas MacArthur and his family from Corregidor. Bulkeley was awarded the Medal of Honor, and his feats were celebrated in William L. White’s bestselling book They Were Expendable . Ironically, Pappy Ford was under Hollywood pressure from April 1943 onward to turn the book into a film, but he felt he could not leave Field Photographic and that the war was more important. Screenwriters McGuinness and Frank W. “Spig” Wead kept up the pressure, but Ford resisted, saying that he was “committed to a major operation.”

One spring morning shortly before the Normandy invasion, Ford was resting in his room at London’s elegant Claridge’s Hotel when there was a knock on the door. It was Armistead and Bulkeley. Although he was naked, the filmmaker jumped out of bed, stood at attention, and saluted the PT-boat hero. “I’m proud to salute the man who rescued General MacArthur,” he declared. Bulkeley regarded Ford as eccentric, but the two soon became firm friends.

Five Days Aboard Bulkeley’s PT-Boat

On the night of June 5, 1944, after dispersing his camera crews among the Allied assault groups, Pappy Ford went aboard the heavy cruiser USS Augusta , the flagship of Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk’s Western Task Force. Too excited to sleep, Ford paced the decks that night as the Augusta and the rest of the Allied armada butted through the choppy English Channel toward France. When the historic early hours of Tuesday, June 6, 1944, came, the filmmaker peered through binoculars as the British, American, and Canadian armies started landing across five Normandy beaches.

He saw the high bluffs behind Omaha Beach and the murderous German crossfire that pinned down elements of the U.S. 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions there for several critical hours on D-Day. The Augusta was some distance offshore, and Ford grew restless; he wanted to get close to the action. So he sent a radio message to Armistead, who was aboard Bulkeley’s PT-boat, and told him to come and pick him up. The boat duly eased alongside the cruiser, and Ford was swung aboard in a boatswain’s chair.

Bulkeley briefed the filmmaker on his boat’s operations, which had included ferrying undercover agents in and out of Normandy and which now centered on beachhead patrols and keeping German U-boats away from the Allied ships. Ford enjoyed himself for five days aboard the PT-boat, standing watch on the cramped bridge, getting a ringside taste of combat when the craft skirmished with enemy E-boats off Cherbourg, and growing to admire the gallant, unassuming Bulkeley. He told Ford frankly that his service in the Philippines had been exaggerated in White’s book, that he had received too much publicity, and that he had not deserved the Medal of Honor.

The five days with Bulkeley convinced Ford that the hero’s story could be told on the screen and that he was the one to direct it. Vacillating no longer, he said, “I frankly admit that I am getting as enthusiastic as hell about They Were Expendable .”

They Were Expendable

Two weeks after the Normandy landings, the bulk of Ford’s film unit sailed home. The weary director checked into a New York hotel, slept for 12 straight hours, and then headed for the West Coast. After agreeing to produce and direct They Were Expendable for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, he summoned writers McGuinness and Wead and put them to work on the script. Wead, an early record-breaking naval aviator before being partially paralyzed in a staircase fall, had penned screenplays for many films about the Navy, including Dirigible , Hell Divers , Ceiling Zero , Submarine D-1 , Dive Bomber , and Destroyer .

Ford went on detached duty from the Naval Reserve in October 1944, and he and Wead honed a final script, focusing on the PT-boat squadrons that fought delaying actions against Japanese invaders in the Philippines early in 1942. It was a saga of gallant sacrifice in the face of heavy odds. Shooting on the film began around Key Biscayne, Florida, early in February 1945. The Navy loaned MGM several PT-boats and their crews, and Biscayne Bay stood in for Manila Bay in the action scenes.

The director chose boyish actor Robert Montgomery to portray the lead character, Lieutenant John Brickley, based on Bulkeley. Ford had to arrange for the Navy to release Montgomery from duty. Montgomery had commanded a PT-boat in the Solomon Islands, served on a destroyer off Normandy, and been decorated. Brickley’s brash executive officer, Lieutenant Rusty Ryan, was played by John Wayne, who said, “Jack was awfully intense on that picture and working with more concentration than I had ever seen. I think he was really out to achieve something.” Although he revered Ford, Wayne was regularly bullied on the set by Ford until Montgomery stepped in on his behalf. The film’s supporting cast included Donna Reed, Ward Bond, Jack Holt, Pennick, Marshall Thompson, and Leon Ames.

“Poet With a Camera”

Because of the Japanese surrender in September 1945, MGM delayed the release of the film until the following December. Its world premiere at Loew’s Capitol Theater in Washington on December 19 was attended by many Hollywood and military luminaries, including Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Moving and sometimes poetic, They Were Expendable was critically acclaimed. Nation magazine reviewer James Agee called it “so beautiful and so real.” But audiences were limited because filmgoers had grown tired of war stories, and the powerful imagery of Ford’s creation was not generally appreciated for several years.

The producer-director, meanwhile, remained active with Field Photographic and Colonel Donovan despite his failing health. While his film unit aided the OSS in gathering evidence about Nazi war criminals, Ford oversaw the disbanding of Field Photographic and purchased an eight-acre tract near Encino, California, where a recreation retirement center was established for the 180 cameramen who had served under him. Donovan pinned the Legion of Merit on the “poet with a camera” in September 1945.

In the postwar years, Ford was best known for a string of screen masterpieces about the American West, but he also directed four more documentaries, including two about the Korean War and two more films about the Navy. These were the comedy-drama, Mister Roberts , starring Henry Fonda and James Cagney, and the biographical The Wings of Eagles , with John Wayne portraying Ford’s longtime friend Spig Wead.

Pappy Ford retired from the Naval Reserve with the rank of rear admiral in 1951. Five months before he died of cancer on August 31, 1973, he was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Richard M. Nixon. At his funeral, Ford’s coffin was draped with the frayed American flag he had filmed being hoisted by Marines at Midway.

Back to the issue this appears in

Join The Conversation

4 thoughts on “ “john ford’s navy”: a filmmaker in the oss ”.

Good to read this, I was looking for some record of the memorial for Ford’s photographers. As a neighbor we boys of the Reseda, Erwin Street neighborhood, got to swim in the estate pool, got to see Henry Fonda, John Wayne, Harry Carey Junior and Senior, and listen to the bagpipers every memorial day; and ride some of the estate burro’s, and let some of the horses munch on our abundant volunteer alfalfa. It was a lot of fun. One of the boys saved a woman from drowning in the pool with her enfant child. I like to believe Ford and his men were an inspiration. D. Hutton

This has some of the best information that I have read on John Ford and others. My Dad was in Ford’s unit. The stories were amazing to hear. The Farm was so much a part of my life.

My great-uncle Joseph August was an Academy nominated cameraman and the founder of the A.S.C. He was also good friends with John Ford–even back to the days of Thomas Ince and Frances Ford! Joe was a member of the OSS with John Ford and was on John’s yacht often. I did find a photo that was in the newspapers about John Ford and cameramen (naming Joseph August) in the summer of 1941 as these people being in the Naval Reserve. I believe they had been preparing for sometime for what was yet to come!

This is a wonderful article. I am a history teacher and have been interested in the life of John Ford for many years. I have a question, maybe someone who sees this can give me an answer. Was John Ford ever on the USS Hornet? Did his crew ever film the Doolittle raid?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Share This Article

- via= " class="share-btn twitter">

Related Articles

Nick “Cooky” Kukich: Covert Operative in Albania

Operation Barbarossa: Holding the Line at Smolensk

The Fight for Singling

Panzer Fury at Caen

From around the network.

Military History

Fighting for the Hook

Famous Military Spies: Ralph Van Deman

The Imjin War: The Japanese Invasion of Korea

Continental Army Captain Nathan Hale

Araner One who hails from the Aran Islands, which are located off the western coast of Ireland, just outside the entrance to Galway Bay. (IX-57: dp. 147; 1. 106'5"; b. 25'2"; dr. 10'6"; s. 8 k.) Faith-a wooden-hulled auxiliary ketch built in 1926 at Essex, Mass., by the Arthur D. Story Shipyards-was acquired by motion picture director John Ford in June 1934, refurbished, and renamed Araner in honor of the Aran Islands, whence his wife's family had come. During the 1930s, the yacht, "an impressive symbol of the wealth and power of her owner " served as a place where Ford could escape the bustle of Hollywood in the company of friends. The famed film director was appointed a lieutenant commander in the United States Naval Reserve in September 1934 and, according to one of his biographers, used Araner off Baja California for intelligence-gathering operations. In 1940, the commandant of the I 11th Naval District commended Ford for his ". . . initiative in securing valuable information. on that region. After he was recalled to active duty in the summer of 1941, however, Ford had little use for his yacht. Shortly thereafter, America's entry into World War 11 in December 1941 prompted the Navy to acquire many private vessels-Araner among themfor local patrol duties. Taken over on a bare-boat charter on 27 January 1942, Araner was delivered to the Navy at the section base at San Diego, Calif. Classified as a miscellaneous auxiliary, and given the designation IX-57, she was placed in service on 26 February 1942. Assigned initially to the I 11th Naval District and then, on 23 July 1942, to the Western Sea Frontier, the ketch operated out of San Diego, under sail power for much of the time, patrolling off Guadalupe and San Clemente Islands. Transferred back to the 11th Naval District forces upon completion of her duties under the Commander Western Sea Frontier, Araner was laid up at the Naval Frontier Base, San Diego, on 1 May 1944; and her crew transferred to YAG-6. Delivered to Mrs. John Ford on 12 July 1944, Araner was struck from the Navy list on 14 October 1944. Ford continued to use the yacht until her rising operating expenses prompted him to sell her circa 1971. Acquired by Fran M. Dimond, of Honolulu, the craft retained her name into 1974, when she was bought by the San Marino Travel Service. Still homeported at Honolulu, she was given back her original name, djammer, Faith in, or about, 1975. Renamed again, to Wind' ne a short time later, she was acquired by the Guam Rent-a-Car Company and served as a tourist-carrying craft into the early 1980s.

© 1996-2022 Historycentral.com Inc . All Rights Reserved.

John Ford Araner

Leave a Comment Cancel

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Email Address:

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

This Famed Director Was Used to Saying ‘Action,’ Now He Would Experience Some For Himself at Midway

On the afternoon of December 7, 1941, director John Ford and his wife were attending a luncheon at the home of Rear Admiral Andrew C. Pickens in Alexandria, Virginia. The host excused himself to take a call from the War Department. When he returned, he told his guests that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. “We are at war,” he said.

Ford was ready.

He had been born John Martin Feeney in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, on February 1, 1894, the son of Irish immigrants who had settled in nearby Portland, where the elder Feeney operated a bar. Young John played on the Portland High School football team and graduated in 1914. His high school nickname, probably because of his football prowess, was “Bull.”

When Feeney’s older brother Francis headed west and found work as an actor and director in California, young John followed—and assumed his brother’s stage name of Ford as well. Eventually John Ford began directing his own films. By the time of Pearl Harbor he was one of Hollywood’s most respected directors, with a resume that included The Iron Horse (1924), Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941), and even a Shirley Temple film, Wee Willie Winkie (1937). In his 1939 Western Stagecoach , Ford turned a relatively obscure actor named John Wayne into a star. That was also the first movie Ford shot in the Southwest’s Monument Valley, a setting he made iconic in his postwar Westerns.

Yet for all his talent, John Ford was a flawed human being with a strong streak of pure New England cussedness. “Actors were terrified of him because he liked to terrify them,” said John Carradine, who acted for Ford in several films. “He was a sadist.” Ford became known for the way he needled his actors, especially Wayne, during filming and for his tendency to go on drunken benders between projects. According to one acquaintance, “It was as though God had touched John Ford at the beginning of his life and said, ‘How would you like to be a very unique man—like no one else. However, you may scare some people.’”

Ford had always nursed a love for the sea, perhaps inspired by his youth on Maine’s Casco Bay. In the 1930s he enlisted in the Navy Reserve with a commission as a lieutenant commander, and as tensions with Japan increased, he sometimes used his yacht Araner to shadow any Japanese vessels he encountered off the California coast. He started the Eleventh Naval District Motion Picture and Still Photographic Group in 1939 as a means of documenting the navy’s activities in the impending war and began recruiting friends from all aspects of the film industry to help. As he later said, “They are writers, directors, some actors, but mostly technicians, electricians, cutters, sound cutters, negative cutters, positive cutters, carpenters, and that sort of thing.” The navy called the 47-year-old Ford to active duty in September 1941 as a lieutenant commander and he went to Washington, where his photographic unit was assigned to work under William J. Donovan , the head of the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency.

In his new role Ford visited Iceland and Panama to survey the military situations there. After the attack on Pearl Harbor he received orders to head to Hawaii to film the aftermath. He and a crew embarked on the trip west on January 4, 1942. Twelve days later he was at Pearl Harbor, which he found “in a state of readiness. The Army and the Navy, all in good shape, everything taken care of, patrols going out regularly, everybody in high spirit[s]…”

On April 18, 1942, Lt. Col. James Doolittle and his raiders took off in twin-engine B-25 Mitchells from the carrier USS Hornet to bomb Tokyo. Although the Doolittle Raid did little physical damage to Japan, it dealt a psychological blow. Shocked by the American attack on its mainland, the Japanese military decided to move aggressively across the Pacific to prevent any more raids. One of its targets was a tiny atoll with an airstrip 1,110 miles northwest of Hawaii called Midway. It was little more than a speck in the vast Pacific, populated mostly by a species of albatross that people called gooney birds, but Midway was also the U.S. Navy’s westernmost base and home to a Marine detachment. Pan American World Airways had used Midway as a base for its Clippers, and navy submarines fueled there, too. A pair of Japanese destroyers had shelled Midway on the night of December 7, 1941, and the Japanese speculated that perhaps Doolittle’s men had taken off from the atoll for their attack. Furthermore, Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the mastermind behind the Pearl Harbor attack, believed that if he threatened Midway, he could draw the U.S. Pacific Fleet under Admiral Chester W. Nimitz out from Hawaii and into battle.

The U.S. Navy had cracked Japanese codes and knew that Midway was in the crosshairs, and Nimitz wanted Ford to photograph the fighting once it erupted. Sometime in late May 1942 he summoned Ford to his office at Pearl Harbor, said he had a dangerous assignment for him, and told him to report to Admiral David W. Bagley. Ford and cameraman Jack Mackenzie Jr. were soon zipping across the harbor in a speedboat for a rendezvous with a destroyer that was already underway. “Hadn’t the slightest idea what I was doing, where I was going,” Ford said. “I found out when I got on board the destination was Midway.”

All was quiet on Midway when Ford and Mackenzie arrived. “All the year around it’s the same out there on that little Pacific island,” Mackenzie told American Cinematographer magazine. “The grandest place in the whole ocean to find absolute quiet and peace—if that’s what you want.” Ford spent time photographing the island’s gooney birds and the PT boats that had accompanied the task force. He remained doubtful that the Japanese would really attack but, forewarned by the codebreakers, the navy had been scrambling to bolster the atoll’s defenses by flying in more aircraft and reinforcing the ground forces. “By June 4 there were 121 combat planes, 141 officers and 2,886 enlisted men on the atoll,” noted Samuel Eliot Morison in his history of naval operations during the war.

On June 3, Ford said, Commander Massie Hughes invited him aboard a PBY Catalina flying boats for a patrol. At first they saw nothing, Ford claimed, but then they got a glimpse of enemy vessels through a break in the clouds. When a couple of Japanese airplanes appeared to spot the PBY, Hughes headed into the clouds, and then descended for a wave-hugging return to Midway.

Something, Ford realized, “was about to pop.” Another Catalina spotted what appeared to be the Japanese invasion fleet and the commander of Naval Air Station Midway, Captain Cyril T. Simard, sent out B-17s and Catalinas to attack the vessels, with little result. Simard expected the Japanese to attack the next morning and suggested that Ford place himself on top of the powerhouse, where he would have a good view of the impending action as well as a telephone link to headquarters. Ford and Mackenzie set up and went to bed.

Simard was right about the attack, although the morning of June 4 started off calmly enough. “Everything was very quiet and serene,” Ford said. He and Mackenzie shared the powerhouse with some Marines who had also stationed themselves on the roof. The filmmakers had a pair of 16mm cameras loaded with color film. Sometime around 6:30 that morning Ford was scanning the sky with binoculars when he spotted the first black dots that meant incoming Japanese aircraft. There were 108 airplanes in all, including 36 Nakajima B5N “Kate” bombers, 36 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers, and 36 Mitsubishi A6M “Zero” fighters, and they had been launched from four carriers about 200 miles out to sea. Midway’s radar had already picked them up and the defenders were braced for the onslaught. “Everybody was very calm. I was amazed, sort of, at the lackadaisical air everybody took,” Ford said. It was as though this kind of thing happened all the time.

The Japanese planes roared in to attack. According to Ford, the lead pilot shocked everybody by flipping his Zero on its back and flying upside down about 100 feet off the ground in a show of bravado. “Everybody was amazed, nobody fired at him, until suddenly some Marine said, ‘What the Hell,’ let go at him and then shot him down,” said Ford. “He slid off into the sea.”

Then the attack started “in earnest.” Bombs exploded nearby, shaking the cameras. A plane dropped a bomb on the garrison’s hangar, which exploded. A piece of concrete struck Ford in the head and briefly knocked him out. “Just knocked me goofy for a bit, and I pulled myself out of it.” Recovering, Ford continued to film despite also receiving an ugly, three-inch shrapnel wound in his arm.

Mackenzie, who kept a lucky rabbit’s foot in his pocket, had also been knocked down by the blast, and he regretted missing a shot of the explosion because he had been reloading film when it happened. He recovered and scrambled down a ladder to the ground and resumed shooting. “By this time [the Japanese] had riddled the hangars and set them on fire,” he recalled. “The hospital too was smashed and on fire, and the commissary was all busted up and burning fierce and one of our oil tanks was on fire sending a plume of heavy black smoke up into the atmosphere. It was a merry little hell all around.”

It appeared to Ford that the Japanese avoided bombing the runway, perhaps, he thought, because they hoped to capture the island and use it later. They did bomb alongside it, and they focused a lot of attention on an airplane the Americans had left out in the open as a decoy. From what Ford saw, the enemy wasted a lot of effort to destroy it. “[T]hey lost about three planes trying to get to that fake plane, as it came into a cone of fire that was pretty dangerous,” he said.

One incident that angered Ford happened as he peered through his binoculars and saw a Zero attack and kill a Marine who had bailed out of his airplane. “This kid jumped and this Zero went after him and shot him out of his harness,” he said, and then the Japanese pilot returned to strafe the water where the Marine had come down.

Ford told his debriefers how impressed he had been by the Marines around him. “They were kids, oh, I would say from 18 to 22, none of them were older. They were the calmest people I have ever seen. They were up there popping away with rifles, having a swell time and none of them were alarmed.” He added, “I was really amazed. I thought that some kids, one or two would get scared, but no, they were having the time of their lives.”

But not all of them had escaped with their lives. Forty-nine of the atoll’s Marine defenders had been killed. Their aircraft—F4F Wildcats and obsolete F2A Brewster Buffaloes—were outmatched by the Japanese Zeros, and attacks flown from Midway against the Japanese vessels proved inconsequential at best and resulted in the loss of more aircraft.

The attack on the atoll lasted only about 20 minutes. The Japanese did not return to follow it up with an invasion because they ran into difficulties out to sea. Yamamoto had accomplished his goal of drawing the Pacific Fleet into battle, but the results were not what the Japanese had desired. American carrier-based dive bombers pounced on the Japanese ships and sank four of its aircraft carriers—and one reason the American airplanes found the enemy ships at a disadvantage is because the carriers had to recover, refuel, and rearm the aircraft that had returned from the attack on the island. Although the U.S. lost the carrier Yorktown , the Battle of Midway at sea proved to be a disaster for Japan and a turning point in the Pacific war.

Ford returned to the United States with the raw footage from his small portion of the fight as well as footage shot by another of his cameramen, Lieutenant Kenneth M. Pier, who had been aboard the carrier Hornet at sea. He began shaping the footage into a short film with the assistance of some Hollywood friends—Henry Fonda and Jane Darwell from The Grapes of Wrath provided voices, Donald Crisp from How Green Was My Valley added narration, and Alfred Newman, who oversaw music for Twentieth Century-Fox, wrote the score. Ford insisted that his editors include a brief shot of Major James Roosevelt, the president’s son, in the final cut. If he did that to curry favor with Roosevelt, it worked. After screening the 18-minute short at the White House, the president told his chief of staff, “I want every mother in American to see this film.” The Battle of Midway began appearing in theaters, as a short before the main feature, in September. Critic James Agee called it “a brave attempt to make a record—quick, jerky, vivid, fragmentary, luminous—of a moment of desperate peril to the nation.”

“Even now, far removed from Midway and the war, The Battle of Midway resonates,” wrote Ford biographer Scott Eyman. “It remains one of Ford’s great achievements.”

Ford had a bumpier experience with another film from his unit. Cinematographer Gregg Toland had taken the lead in putting together a documentary about the Pearl Harbor attack, but the military men who previewed the work gave it scathing notices. They objected to the way the filmmakers had recreated events for their cameras, the film’s virulent portrayal of the Japanese, and the way it left the “distinct impression that the Navy was not on the job,” in the words of Admiral Harold Stark. Ford had it recut from 85 minutes to 34, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences voted December 7th best short documentary at the 1944 Oscars.

Ford continued his work for the navy. He ventured into harm’s way again in late 1942 when he oversaw shooting in North Africa. One person he encountered there was Darryl F. Zanuck, the production chief of Twentieth Century-Fox, for whom Ford had made The Grapes of Wrath and How Green Was My Valley . Zanuck had received a commission in the Signal Corps and was working on his own documentary. “Can’t I ever get away from you?” Ford grumbled to him. “I’ll bet a dollar to a doughnut that if I ever go to Heaven, you’ll be waiting at the door for me under a sign reading, ‘Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck.’”

Ford later went to Asia to film activity in Burma and China, and in June 1944 he supervised filming of the D-Day landings, activity marred when he went on an epic three-day bender in mid-June. Once he sobered up, Ford spent time aboard a PT boat commanded by John D. Bulkeley, who had rescued Douglas MacArthur from Corregidor in March 1942 and was the centerpiece of William Lindsay White’s book They Were Expendable , an account of PT boat crews in the Philippines. (See “Battle Films,” page 76.) When Ford returned to the United States to start work on the film version of White’s book, his time in the war zones were over.

After the war, Ford continued his film career, directing a series of classic Westerns with John Wayne. (Ford enjoyed needling Wayne over his lack of service in the military.) Those films included Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and The Searchers (1956). The director is now considered one of the great artists of Hollywood’s Golden Age. When filmmaker Orson Welles, no slouch behind the camera himself, was asked who his three favorite directors were, he answered “John Ford, John Ford, John Ford.”

For the rest of his days, until he died in 1973, Ford remained proud of his navy service and was “shameless” in his pursuit of official medals and ribbons. Befitting a man who had a character in one of his movies say, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” Ford often burnished the legend of his experiences at Midway and elsewhere. In truth, he had no need to embellish.

this article first appeared in world war II magazine

Related stories

Portfolio: Images of War as Landscape

Whether they produced battlefield images of the dead or daguerreotype portraits of common soldiers, […]

Jerrie Mock: Record-Breaking American Female Pilot

In 1964 an Ohio woman took up the challenge that had led to Amelia Earhart’s disappearance.

Celebrating the Legacy of the Office of Strategic Services 82 Years On

From the OSS to the CIA, how Wild Bill Donovan shaped the American intelligence community.

10 Pivotal Events in the Life of Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (1846-1917) led a signal life, from his youthful exploits with the Pony Express and in service as a U.S. Army scout to his globetrotting days as a showman and international icon Buffalo Bill.

| BLACK DOUGLAS | 2 Jan 42 | Bath IW | 22 Nov 29 | 9 Jun 30 | 18 Apr 42 | ARANER | 27 Jan 42 | A. D. Story | -- | 1926 | 26 Feb 42 | DWYN WEN | 4 Feb 42 | Philip & Son | -- | 1906 | 19 Feb 42 | VOLADOR | 2 Feb 42 | Wm. Muller | -- | 1926 | 19 Feb 42 | SEAWARD | 31 Jan 42 | Adams, E. Boothbay | -- | 1920 | 19 Feb 42 | GEOANNA | 1 Feb 42 | Craig SB, Long Beach | -- | 1934 | 19 Feb 42 | VILEEHI | 19 Dec 41 | San Diego Marine | -- | 1930 | 26 Feb 42 | ZAHMA | 8 Jan 42 | George S. Lawley & Sons | -- | 1915 | 26 Feb 42 |

| BLACK DOUGLAS | 20 Sep 44 | 14 Oct 44 | 4 Oct 44 | RTO | -- | ARANER | 1 May 44 | 14 Oct 44 | 12 Jul 44 | RTO | -- | DWYN WEN | 1 Apr 43 | 18 Jul 44 | 6 Jan 45 | MC/S | 6 Jan 45 | VOLADOR | ca Apr 43 | 3 Sep 43 | 17 Aug 43 | Army | -- | SEAWARD | 1 Apr 43 | 18 Jul 44 | 6 Apr 45 | MC/S | 6 Apr 45 | GEOANNA | ca Apr 43 | 3 Sep 43 | 20 Aug 43 | Army | -- | VILEEHI | 20 Sep 45 | 24 Oct 45 | 27 Sep 45 | RTO | -- | ZAHMA | 13 Apr 43 | 18 Jul 44 | -- | RTO | -- |

| BLACK DOUGLAS | Ex yacht BLACK DOUGLAS, Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior Dept. Auxiliary 3-masted schooner. Steel hull. Specifications above. To PYc-45 8 Apr 43 and commissioned 19 Apr 43. | ARANER | Ex yacht ARANER, ex FAITH 1934. Auxiliary ketch. 100 tons light, 147 tons gross. 106.4' oa, 86.0' reg x 25.2' x 10.5'. Wood hull. 1 Atlas Imperial diesel, 100 HP, 8 kts. | DWYN WEN | Ex yacht DWYN WEN. Auxiliary schooner. 110 tons light, 86 tons gross. 104.0' oa, 84.0' wl x 20.0' x 13.25'. Composite hull. 1 Atlas Imperial diesel (fitted 1926), 75 HP, 7 kts. Designed by Alex. Richardson and built at Dartmouth, England, she was acquired from Eugene Overton of Los Angeles, Calif., to whom she was sold back in January 1945. She resumed service as the yacht DWYN WEN and still existed in 2006. | VOLADOR | Ex yacht VOLADOR. Auxiliary schooner. 90 tons light, 114 tons gross. 110.0' oa, 85.8' wl x 23.4' x 12.25'. Wood hull. 1 Atlas Imperial diesel, 120 HP, 7 kts. Designed by William Gardiner, built at Wilmington, Calif., and acquired from W. L. Valentine. Not registered for postwar service as an American yacht. | SEAWARD | Ex yacht SEAWARD. Auxiliary schooner. 100 tons light, 96 tons gross. 106.0' oa, 90.0' wl x 21.6' x 14.0'. Wood hull. 1 Western diesel (fitted 1937), 65 HP, 7 kts. Designed by John G. Alden and built at East Boothbay, Maine. Acquired from Cecil B. deMille, for whom she had probably been built. Sold in April 1945 to Charles A. Williams of San Pedro, Calif., and resumed service as the yacht SEAWARD. Transferred to French registry 1951. | GEOANNA | Ex yacht GEOANNA. Auxiliary schooner. 90 tons light, 122 tons gross. 111.5' oa, 81.5' wl x 22.5' x 14.75'. Steel hull. 1 Superior diesel, 135 HP, 8 kts. Designed by George L. Craig and built at Long Beach, Calif. Requisitioned by the MC from the Seven Up Bottling Co., which had purchased her in 1938. Probably resumed service as a yacht under foreign registry after the was, was named LANIKAI II during the 1980s. | VILEEHI | Ex yacht VILEEHI. Auxiliary ketch. 90 tons light, 54 tons gross. 80.0' oa, 61.4' wl x 19.25' x 11.4'. Wood hull. 1 Sterling gas engine, 116 (or 75) HP, 7 kts. Designed by Edson B. Schock and built at San Diego, Calif. Acquired in 1941 from Hiram T. Horton, for whom she had been built. Returned to him in 1945, she resumed service as the yacht VILEEHI and was still in service in 2002. | ZAHMA | Ex yacht ZAHMA. Auxiliary ketch. 100 tons light, 157 tons displacement, 75 tons gross. 94.0' oa, 69.0' wl x 20.75' x 7.75'. Wood hull. 1 Superior diesel (fitted 1937), 100 HP, 8 kts. Designed by B. B. Crowninshield and built at Neponset, Mass. Chartered from her owner, R. S. Rheem of Los Angeles, who recovered her in 1945 and returned her to service as the yacht ZAHMA. She was renamed THESPIAN in 1957 and was removed from documentation in 1967. |

- Articles incorporating text from the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships

- Articles incorporating text from Wikipedia

- Unclassified miscellaneous vessels of the United States Navy

- Ships built in Massachusetts

- Essex, Massachusetts

USS Araner (IX-57)

| USS Araner (IX-57) | |

|---|---|

| Career (US) | |

| Builder: | Arthur D. Story Shipyards |

| Laid down: | 1926 |

| Acquired: | 27 January 1942 |

| In service: | 26 February 1942 |

| Struck: | 14 October 1944 |

| Fate: | Unknown |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 147 Tons |

| Length: | 106 ft 5 in (32.44 m) |

| Beam: | 25 ft 2 in (7.67 m) |

| Draft: | 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m) |

| Speed: | 8 knots |

USS Araner was a wooden-hulled auxiliary ketch built in 1926 at Essex, Massachusetts by the Arthur D. Story Shipyards and acquired by motion picture director John Ford in June 1934. Originally named Faith , she was refurbished, and renamed Araner in honor of the Aran Islands , whence his wife's family had come. During the 1930s, the yacht served as a place where Ford could escape the bustle of Hollywood in the company of friends. The film director was appointed a Lieutenant Commander in the United States Naval Reserve in September 1934 and, according to one of his biographers, used Araner off Baja California for intelligence-gathering operations. In 1940, the commandant of the 11th Naval District commended Ford for his "… initiative in securing valuable information…" on that region.

After he was recalled to active duty in the summer of 1941 however, Ford had little use for his yacht. Shortly thereafter, America's entry into World War II in December 1941 prompted the US Navy to acquire many private vessels and Araner was among them, for local patrol duties. Taken over on a bareboat charter on 27 January 1942, Araner was delivered to the US Navy at the section base at San Diego, California. Classified as a miscellaneous auxiliary and given the designation IX-57, she was placed in service on 26 February 1942. Assigned initially to the 11th Naval District and then, on 23 July 1942, to the Western Sea Frontier , the ketch operated out of San Diego, under sail power for much of the time, patrolling off Guadalupe and San Clemente Islands .

Transferred back to the 11th Naval District forces upon completion of her duties under the Commander, Western Sea Frontier, Araner was laid up at the Naval Frontier Base San Diego on 1 May 1944; and her crew transferred to YAG-6. Delivered to Mrs. John Ford on 12 July 1944, Araner was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 14 October 1944.

Ford continued to use the yacht until her rising operating expenses prompted him to sell her circa 1971. Acquired by Fran M. Dimond, of Honolulu, the craft retained her name into 1974, when she was bought by the San Marino Travel Service . Still homeported at Honolulu, she was given back her original name, Faith in, or about, 1975. Renamed again, to Windjammer , a short time later, she was acquired by the Guam Rent-a-Car Company and served as a tourist-carrying craft into the early 1980s.

Sources [ ]

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships . The entry can be found here .

NavSource Online: Service Ship Photo Archive

| Comments, Suggestions, E-mail . |

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

USS Araner was a wooden-hulled auxiliary ketch, designed by Jack Hanna, built in 1926 at Essex, Massachusetts by the Arthur D. Story Shipyards, and acquired by motion picture director John Ford in June 1934. Originally named Faith, she was refurbished and renamed Araner in honor of the Aran Islands, whence Ford's family had come.. During the 1930s, the yacht served as a place where Ford could ...

Historical: USS Araner was a Jack Hanna-designed wooden-hulled auxiliary ketch built in 1926 at Essex, Massachusetts by the Arthur D. Story Shipyards and acquired by motion picture director John Ford in June 1934. Originally named Faith, she was refurbished, and renamed Araner in honor of the Aran Islands, whence his wife's family had come.

Faith, a wooden-hulled auxiliary ketch built in 1926 at Essex, Mass., by the Arthur D. Story Shipyards, was acquired by motion picture director John Ford in June 1934, refurbished, and renamed Araner in honor of the Aran Islands, whence his wife's family had come. During the 1930s, the yacht, "an impressive symbol of the wealth and power of her ...

As the log of the Araner records, Ford, Wayne, Bond, and Fonda got themselves arrested on New Year's Eve 1934 in Mazatlan—twice. The second time they were bailed out, town officials "invited" them to leave. But all that south-of-the-border debauchery provided cover for a more purposeful aspect of Ford's yacht excursions.

But 46-year-old Ford, the owner of the Araner, a 110-foot, two-masted yacht, also dreamed of becoming a naval hero, although he had failed the entrance examination for the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1914. He was sure that his country would be drawn into the conflict, offering him his "last chance to be a boy.".

Delivered to Mrs. John Ford on 12 July 1944, Araner was struck from the Navy list on 14 October 1944. Ford continued to use the yacht until her rising operating expenses prompted him to sell her circa 1971. Acquired by Fran M. Dimond, of Honolulu, the craft retained her name into 1974, when she was bought by the San Marino Travel Service.

Araner. Two ships of the United States Navy have been named Araner for one who hails from the Aran Islands . USS Araner (IX-57), was a wooden-hulled auxiliary ketch named Faith built in 1926 and acquired by the Navy on 27 January 1942. USS Araner (IX-226), was the Liberty ship Juan de Fuca acquired by the Navy on 23 September 1945.

Araner - (IX-57) - USS Araner was a Jack Hanna-designed wooden-hulled auxiliary ketch built in 1926 at Essex, Massachusetts by the Arthur D. Story Shipyards and acquired by motion picture director John Ford in June 1934. Originally named Faith, she was refurbished, and renamed Araner in honor of the Aran Islands, whence his wife's family had come.

Susan Henriquez on International Yacht Restoration School (Newport, Rhode Island USA) Craig Davis on ClassicSailboats.Org; Robert Albrecht on Theodore D. Wells KARINA; Pascal Lalanne on Bruce King SIGNE; Peter Noyes on L. Francis Herreshoff TIOGA II; Capt. jeff engholm on Herreshoff Ketch Landfall - Mystery Solved; Carlene Crowe on George ...

Ford had always nursed a love for the sea, perhaps inspired by his youth on Maine's Casco Bay. In the 1930s he enlisted in the Navy Reserve with a commission as a lieutenant commander, and as tensions with Japan increased, he sometimes used his yacht Araner to shadow any Japanese vessels he encountered off the California coast. He started the ...

IX-57: On 30 Jan 42 CNO asked BuShips to negotiate with the owner of the motor yacht ARANER for her acquisition for the sum of $1.00 per year. The owner was John Ford, the motion picture director who became a Naval Reserve officer in 1934, the year he purchased the yacht. The yacht, designed by John G. Hanna and built at Essex, Mass., was ...

Episode 2 - The AranerFord buys a yacht, named after the Aran Islands off Ireland, where he cavorts, drinks and vacations. But he also keeps an eye on the l...

USS Araner was a wooden-hulled auxiliary ketch built in 1926 at Essex, Massachusetts by the Arthur D. Story Shipyards and acquired by motion picture director John Ford in June 1934. Originally named Faith, she was refurbished, and renamed Araner in honor of the Aran Islands, whence his wife's family had come.During the 1930s, the yacht served as a place where Ford could escape the bustle of ...

Place in service as Araner (IX-57), 26 February 1942 Placed out of service and laid up at Naval Frontier Base, San Diego, CA., 1 May 1944 Returned to her owner, 12 July 1944 Struck from the Naval Register, 14 October 1944 Registered in 1961 by John Ford Productions, Honolulu, HI., as Araner;

John G. Hanna. John Griffin Hanna (1889-1948) was a sailboat designer, famous for designing the Tahiti ketch. Hanna was born in Galveston, Texas, on October 12, 1889. During his childhood he was afflicted with deafness following scarlet fever and lost a foot in a traffic accident. Around 1917, he settled in Dunedin, Florida, and was greatly ...

His pride and joy was his yacht, Araner (yacht), which he bought in 1934 and on which he lavished hundreds of thousands of dollars in repairs and improvements over the years; it became his chief retreat between films and a meeting place for his circle of close friends, including John Wayne and Ward Bond.

Tweet. #2. 02-07-2008, 10:46 PM. Re: John Ford's Araner... Ford continued to use the yacht until her rising operating expenses prompted him to sell her circa 1971. Acquired by Fran M. Dimond, of Honolulu, the craft retained her name into 1974, when she was bought by the San Marino Travel Service. Still homeported at Honolulu, she was given back ...

Re: John Ford's Araner... Regarding the Yacht Araner, I lived in Kailua from 1956 to 1962, spent time in the sea scouts and worked on the Araner, and sailed on her. I remember Rip Yeager and enjoyed working on the boat. In all my time in Kailua the Araner always anchored in Kaneohe Bay. Had to ride the shore boat out to work on her.

Italian authorities in March impounded Russian coal and fertilisers magnate Andrey Melnichenko's $600mn Sailing Yacht A after Russia invaded Ukraine. Another yacht, the $300mn Philippe Starck ...

Reflecting the intricate design, luxury amenities, and superior performance, the Amaryllis yacht is valued at approximately $120 million. The annual running costs are estimated around $12 million. However, the price of a yacht can significantly vary based on numerous factors, including size, age, luxury quotient, and the cost of materials and ...

She claims she is the sole adult beneficiary of the trust that owns the yacht, rather than her billionaire father. Investigating that challenge led the BBC to uncover some £500m worth of assets ...

Гастроли Boney M в СССР. Москва, 1978. Boney M concert tour in the USSR. Moscow, 1978.