- Building a Skerry

- Building a Tender

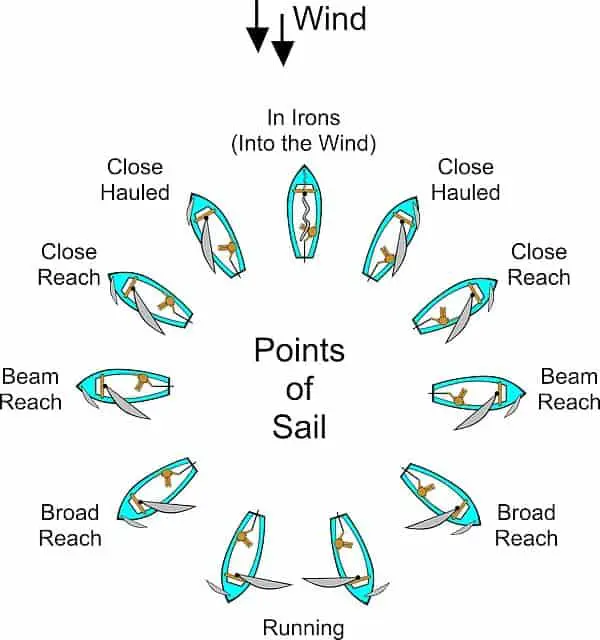

- Points of Sail

- Making Sails

- Boat types, terminology

Nautical Terms Relating to Sails, Rigs and Sailing.

Nautical terminology is confusing for not-so-salty boatbuilders and sailors. Here is the result of my research on sail terminology

If you plan to do any reading on sails and sailing you will need to know these sail terms or at least where to find the meanings. HERE!

If you want me to add another word, just send me an email and I'll add it. I'm hoping here to include the most important terms used to describe sails and sailing and to make it easier for folks who are trying to read and are getting bogged down with the terminology.

The drawings are mine, I'm not a terrific illustrator. Add a new word.

Many beginning boat builders and not so novice find sail terminology confusing, you are not alone.

Test your knowledge with my Sail Quiz

Sail words defined.

I try to be accurate and check my information, but mistakes happen. I don't pretend to be complete either.

Boatbuilding

Small Print

This information is for general knowledge.

Raising and Lowering the Sails

Published by admin on may 27, 2019 may 27, 2019.

On a cruiser, the sails are typically down at the dock and they stay down until the boat is at sea. Of course, if you have no motor, the sails must be used to cast off, but we’ll discuss that later. For now, we’ll assume that the boat is out at sea with the sails tied down.

Raising the Main

The mainsail is raised first, and this can be done with the motor idling. The boat should be pointed with the bow facing into the wind. This alignment means the sail will be luffing when raised, making it easier to bring in the halyard and less likely that the sail will fill unexpectedly and knock the boat around.

The boom vang should be loose so that it does not resist the tension you’ll put on the main halyard. The mainsheet should also be somewhat loose for the same reason, but it shouldn’t be completely free since you don’t want the boom swinging around in an uncontrolled manner.

When the boat is pointing into the wind and the boom vang and mainsheet are loose, the cover and ties can be removed from the main and the halyard brought in to raise the mainsail. The halyard should be able to be pulled in most of the way by hand – if not, there may be something resisting it, such as the boom vang, or it may be caught – and then brought the final one or two feet by using a winch.

Once the sail is fully raised and the halyard cleated, the topping lift should be let out, which will cause the boom to drop slightly, which will flatten out the sail. The boom vang and mainsheet can be tightened again.

Since the boat is pointing into the wind, it’s easiest to start sailing on a close hauled tack. You can use the motor to turn out of irons and then it should be cut off. You’re sailing!

Raising the Jib

The jib should be deployed only after the main is up and the boat is sailing, and the process is fairly simple, whether for a furling or non-furling jib. We’ll assume that the jib shackles are hooked to the forestay if the jib is non-furling. Also it is assumed that the jib sheets are already rigged to run through the fairlead and back to the cockpit.

For a non-furling jib, the sail is simply raised using the jib halyard. The wind fills the sails and the leeward jib sheet is used to set the sail. To prevent the sail from flapping uncontrollably and pulling the jib sheet out of the blocks, the leeward jib sheet can be pulled in slightly prior to raising the jib.

To unfurl a furling jib, the process is even simpler. The furling line is uncleated, but kept taught, and the leeward jib sheet is taken in as the furling line is slowly released. This action unfurls the jib, which immediately fills with wind.

Lowering the sails

Lowering the sails basically involves carrying out the sail hoisting procedure in reverse order. First the jib is lowered or furled, then the main.

The jib can be furled anytime. The boat does not necessarily need to be pointed into the wind, but heading on an upwind tack or being in irons will help the jib furl tighter and more neatly. Keep tension on the active jib sheet, slowly releasing it while brining in the furling line. When the jib is completely furled, the furling line can be cleated.

To bring down a non-furling jib, a crew member needs to go to the bow and pull the jib down by hand, bunching it up. Another crew member should uncleat the jib halyard and release it slowly as the jib is brought down. Also, the jib sheet should be let out slowly, but this can be done after the sail is down if there aren’t enough crew hands to let out the halyard and the jib sheet at the same time. Once the jib is down, it can be held in place temporarily using bungees, to be stowed below deck upon return to the dock.

When lowering the main, it helps to point the boat into the wind, and in some cases the boat can be positioned so that a hill or tall building on shore blocks the wind to make things easier. Similarly to the jib, one crew member slowly lets down the halyard while another pulls the sail down by hand. As the sail is lowered, the bungees or straps used to hold it to the boom are replaced.

This process is best done with one crew standing forward of the mast, bringing down the sail, one crew lowering the halyard, and another wrapping bungees around the sail as it comes down. Obviously, when fewer crew are available, it’s a bit more hectic.

Related Content

Related posts.

Cruising Education

Troubleshooting marine outboard engines.

We've all been there. Eager to jump in the dinghy and land on shore after laying anchor on the mothership. Just one problem, the dinghy outboard wort start.

Education Safety Sailing Basics

Servicing type v personal flotation devices (pfds).

If you're like a lot of recreational boaters, you may not pay a much attention to your life vest. You might not even know what PFD stands for - Personal Floatation Device. You may have even purchased a type V PFD with your #1 criteria being comfort. You throw it on each time you go out, mainly just to make a show of it, and take it off as soon as you're outside the marina - confident that you'll remember to put it back on if the weather picks up.

Best Coffee Brewing Methods for Cruising Sailors

Coffee is life. If you’re like me, you need your cup of joe first thing every morning. There is nothing quite like a great cup of coffee onboard as the sun comes up over your Read more…

Berthon Winter Collection

Latest issue

August 2024

In the August 2024 issue of Yachting World magazine: News Few finish a tempestuous Round The Island Race European rules are eased for cruising to France and Greece Olympic sailing…

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

The best downwind sails: Options explained by over 200 experienced sailors

- Toby Hodges

- June 18, 2024

Which downwind sails are the right choice for you? and how do you take the stress out of sail handling on a tradewind passage? Toby Hodges quizzed more than 240 skippers in last year’s ARC to find out

Downwind sailing is any cruising sailor’s dream. The thought of days, or even weeks, of reliable following tradewind pushing you across an ocean with just a warm apparent breeze over the deck seems particularly far-fetched for those of us who have just suffered the wettest winter imaginable.

We all need a reliable downwind setup, whether coastal cruising or passagemaking. But those planning an Atlantic crossing or Pacific crossing will want to give this aspect particular attention, perhaps adding some tweaks or sail wardrobe investments to help ensure that dream adventure is as comfortable as possible for your crew and your yacht.

While there’s certainly no one-fits-all answer, we can learn a lot from those who have done a crossing. Last year we used our annual ARC Gear Survey to focus on the topic of downwind sails and handling and have since analysed the responses to our detailed questionnaire, from over 240 skippers on the ARC and ARC+ rallies.

The reason why there’s no optimum solution for all is multifaceted. Sure, the shape of your hull and keel type can help narrow down options. Unless you have a sportier design, then sailing the downwind rhumbline should equate to least stress and gybes and therefore potential problems. Those with newer hull shapes may want to calculate their polars and work with sailmakers to evaluate which angles and sails best suit their hulls.

How about your rig – is it easy to use a pole? Is there a track to fit one… or two even? Can you square the boom or do you have swept-back spreaders? Do you sail short-handed or with plenty of crew to help pull strings and get poles down? The answers can lead to yet more considerations, including chafe points, how to avoid rolling, and how to easily depower or reef.

Does your mainsail help and does it fill the slot better when reefed? What’s your best setup for short-handed or at night? What are your backup systems (notably for torn sails or a broken halyard or pole)?

A lot can be answered in advance by considering such questions. The weather, however, cannot. We can only hope for reliable trades and the sort of downwind crossing conditions last year’s ARC crews gratefully experienced.

Photo: Tony Gratton/Niord/WCC

Weighing the options

Spinnakers can be ideal if you have the experience and crew to handle them, their numerous associated lines, and can get them down easily. Asymmetric spinnakers or gennakers can make this handling much easier, as they don’t require a pole. They were carried by over 40% of the fleet last year, making these the most popular offwind option in terms of numbers carried (an indication of a modern fleet), but they don’t suit true downwind sailing, meaning extra miles to sail.

Aero-style vented spinnakers, aka parasailers, can seem like the holy grail for many on a downwind crossing as they can be set from the bow or in front of the boat and are capable of reaching and running. However, these are among the costliest sail options/upgrades and there’s a range of different brands now which all claim the optimum design.

That said, perhaps the clearest message from 2023’s ARC skippers was the real love of – or wish for – a parasailer. Over 40 yachts carried one, yet so many more commented that they would have wanted one. This is perhaps a reflection of last year’s consistent tradewind conditions – “The parasailer was perfect for the conditions we had” said the skipper of German Catana 47 Aquila .

Other downwind sail setups include twin headsails, or the specialist Bluewater Runners and TradeWinds, versatile sails which share a single luff.

However, a poled-out genoa, where the headsail is typically flown wing-on-wing/goosewinged with the mainsail, is still considered the most reliable method for downwinding.

Carrying a range of options is ideal, but remember you also need the space to stow them!

Grand Soleil 46LC Flying into the sunset poled-out. Their twin headsails were “a dream”. Photo: Peter Blackadder/Flying/WCC

Pole-out – belt and braces

Around 60 yachts used a poled-out headsail, with over 40 of these skippers still rating it the most reliable method. It uses your heavier-grade white sails, the mainsail can be securely prevented, and both can be easily reefed.

Asante , a 2007-built Oyster 56, has a gennaker aboard but found: “Best setup when windy is two reefs in main, poled-out headsail – easy solution and fast going at 8-10 knots (we covered 205 miles in 24 hours)”. Serenity , a French HR40, said it “allows for a good wind angle in tradewinds and is easy to reef single-handedly if needed”, while German Bavaria 51 Mola adds this setup is “extremely resistant to squalls”.

A poled-out genoa worked best aboard the Moody 54 Dilema , albeit making for a ‘rolly’ experience: “Simple and effective. We used centred staysail as well to reduce roll.” UK-flagged Rustler 42 Carrik also remarked on the rolling but was otherwise in praise: “sailing goosewinged spared us the drama of the spinnaker when winds were 20-plus knots (which was most of the time) and allowed us to sail the rhumbline”.

The Swedish-flagged Hallberg-Rassy 48 MkII Sally was sailed double-handed so kept it straightforward with main and poled-out headsail, sailing wing-on-wing for two weeks. “Our simple sail approach worked well for us, fast enough and easy.”

Article continues below…

43 of the best bluewater sailboat designs of all time

Which yacht is the best for bluewater boating? This question generates even more debate among sailors than questions about what’s…

10 practical tips for perfect downwind sailing in the Tropics

Between the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn lie the tradewind belts, separated by the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) known to…

Also sailing double-handed was Fisk , a 2007 Oyster 46: “Our poled-out genoa (130%) proved to be a very useful all-round tool, goosewinging with the main when feasible.” They bought these sails new before the ARC but think a light wind sail could have been useful too.

Jeanneau Sunshine 38 Cloud Jumper points out that “goosewinging is less weight on the bow than twin headsails.” They sailed like this for 22 days. And 20-year-old Oyster 53 Jarina had another reason for the ease of this setup: “a foredeck crew with the combined age of 200! Poled-out headsail plus main and preventer equals ease of handling. Stable and controllable.”

Experimenting and enjoying the process should be encouraged. Ipanema developed a motto by doing this: “poled-out genoa if wind greater than 18 knots; gennaker if wind less than 20 knots”. Bestevaer 53ST Aegle thinks having a good solution for various apparent wind angles is key: “goosewing is very effective; a furling spinnaker makes life much easier”.

Twin headsails (one flown free) on Island Packet 380 Niord. Photo: Tor Johnson

Twins – twice as good?

Some bluewater yachts install their own systems as standard, including a pole or twin poles, knowing twin headsails are ideal for tradewind cruising. The Barters on their 20-year old Super Maramu Nunky hail the Amel twin headsail system as “superb: great downwind and they can be furled together in a moment”. Equally, Oyster 54 Ostara says: “the Dolphin twin headsails performed very well – very versatile and fast passagemaking in tradewinds”.

Other skippers might choose to fit or retrofit two forestays or twin luff grooves. “Twin headsails on the same furler worked really well,” is the verdict from Rival 36 Topaz Rival. They sailed like this for 17 days, including at night, so it didn’t affect their watch pattern.

Norwegian Sun Odyssey 44 Moyfrid used genoa and jib poled-out for 15 days, as it’s “easy to adjust, gave us flexibility and safety of handling quickly in squalls”. The same reasoning was given by Discovery 58 Aqualuna, who found twin headsails excellent for double-handing. “It meant we could do three hours on, three hours off”. The summary from Oyster 53 Distraction : “Twin headsails is easy but not fast, asymmetric is fast but not easy.”

The Blackadders’ Grand Soleil 46 Flying has twin headsails, a gennaker and a Code 0, “and trapped the edge of the tradewinds to use them all”. They found “our twin headsails/twin poles worked a dream – easy to fly single-handed and not too rolly.” They also found them easy to adjust and reef, and adaptable to different conditions including winds up to 35° off the quarter.

US-flagged Ovni 450 Reverie running west to the sunset under gennaker. Photo: Tony Martin/Reverie/WCC

Spinnakers – Going deep

Anyone in a hurry, racing or wanting some sport for an active crew would probably choose a spinnaker (or several, space and budget willing). While capable of harnessing those tradewinds most efficiently, a big free-flying sail can be tricky to gybe and get back on deck. A popular ARC solution is to fly a spinnaker during the day and poled-out headsail at night as the latter is easier to manage/reef without affecting the watch system.

Oyster 406 Penny Oyster : “We used the spinnaker during the day (weather permitting) which increased speed and was less rolly. Poled-out jib overnight felt very stable and safe. Easy to manage solo.” It was the same for Grand Soleil 50 Sidney II and 20-year old Sweden Yachts 42 Freedom , the latter promoting: “full main and spinnaker when 15 knots or less (sailed on a dead run for 90% of trip); main and genoa goosewinged if 15 knots or more”.

Symmetrical kites (and parasailers) are often a popular choice for catamarans as they can be set off each bow. Sailing double-handed on their Aussie flagged Outremer 51 Spirit , the McMasters bought a symmetric kite for the crossing to supplement their gennaker, flew it with the mainsail and considered it “easy gybing and conservative for double-handing”. Fellow Outremer Madeleine (a 45) carried Code, A-sails and a symmetric spinnaker and found a “half-reefed main and spinnaker stable and easy”.

Foredeck crew of Estonian Oyster 565 Larimar stow the furled gennaker while under TradeWind. Photo: Magnus Harjak/Larimar/WCC

Asymmetric/Gennaker – working the angles

Despite gennakers being the most popular offwind sail option carried (90 yachts), only around 20 skippers found this to be their most successful sailplan for the crossing, with many frustrated by not having a kite with enough belly to sail the deep downwind angles experienced last year. (While deeper cut asymmetrics are available, many, especially furling types, have a flatter shape and suit reaching more). Grand Soleil 46LC Mandalay reckons their inability to sail deep cost them two days.

Grand Soleil 50 Mr Twister found that flying their gennaker with a double reefed main “allowed for a more downwind course”. This was backed up by the Peckhams on their Hanse 455 Infinity of Yar : “Two reefs in the main allows wind over the top of mainsail so 165-170º TWA is possible”. At night they resorted to the boat’s standard white sails but as this involves a self-tacking jib, they’d want to fit a poled-out genoa or yankee if doing it again.

Handling an A-sail and whether to use a furler or snuffer, also needs due consideration. Najad 490 Adastrina cautions that a “top-down furler with its torsion rope is difficult to stow due to bulk”, while Oyster 47 Aequitas also warns: “Don’t sail too deep as the snuffer jams.”

Code 0s have transformed cruising for many production yachts, particularly those which typically day sail in light winds and want an easily furled fetching or reaching option. However, they are not deemed so useful for tradewind passages as they lack the deeper shape for downwind conditions. “Code 0 was excellent, but could not run deeper than 155°,” confirms new Canadian-flagged X46 Imi Makani .

An exception was perhaps the Oyster 745 Mexican Wave : “We loved both our Elvstrom Code 0, which we flew 10 days and nights, and our Bluewater Runner which was great in light wind. Both on hydraulic furlers – easy.”

Birds-eye view of the deep bellied Bluewater Runner on Hanse 505 Mojito. Photo: David Anning/Mojito/WCC

Specialist sails – Bluewater Runner & TradeWinds

Elvstrom’s Bluewater Runner (BWR) and North Sails’ TradeWind (TW) were purposefully designed for downwind events such as the ARC. They take some of the twin headsail concept, but use lighter fabric and modern furling technology for a versatile multi-use sail.

The twin headsails are joined at the luff and can be flown together on the leeward side to act as a light wind genoa/Code sail equivalent, or peeled apart when running to be flown wing-on-wing, independent of the fixed forestay and headsail. And in principle, they can be easily furled from the cockpit.

Hallberg Rassy 40 Northern Light purchased a BWR for the crossing, used it for 16 days during daylight hours, and found it “very effective when running dead downwind.” The Hanse 505 Mojito agrees: “Worked really well, easy to handle, and doubles up as a Code 0. It gave the best downwind performance and can be managed from the cockpit.” That said, they consider their BWR “too powerful for the rig even in 20 knots of wind – we snapped one halyard and broke the bobstay and bowsprit padeye.”

HR57 Saltair advises it needs lots of halyard tension, while Lagoon 410 Newbee agrees that less than 20 knots wind suits the BWR – they resorted to a triple-reefed main and genoa when things got livelier.

Pinnacle before chafe issues with its TradeWind sail. Photo: Stephanie Stevens/Pinnacle/WCC

North Sails’ latest offerings are popular on modern luxury cruisers. Rock Lobster IV is a new Oyster 565 with a wardrobe of North Sails including a TradeWind and a Helix structural luff gennaker. “Helix is very easy (little point using the G2); TradeWind is great in moderate wind, and poled-out yankee gives good flexibility”. They wisely “adapted sails to crew ability”.

Fellow Oyster Ri-Ra , a 675, also with a new North suit, had “lots of difficulties with TradeWind sails,” however, and blamed a poor setup and “inadequate halyard casting”. Meanwhile Mastegot, a new Oyster 595, found their poled-out jib and main more successful than the TW, and if doing again they’d instead consider twin headsails, “because they can be reefed”.

But there were words of praise from Amel 60 Mrs G who found their TradeWind most reliable with a reefed main, and the Swedish Passad 38 Lulu : “very good lift and speed, much better than wing-on-wing”.

Parasailor – fast, stable and no rolling,” says Contest 50CS Athena. PHoto: Philip Mrosk/Athena/WCC

Parasailers – the vented kite

For want of a generic term ‘parasailers’ are specialist cruising spinnakers with a pressure relief valve. This vented part diffuses gusts while the paraglider-style wing creates lift and provides support to the sail (they don’t require a pole, but can be used with one).

It’s a forgiving, versatile option that can be used for running and reaching, but it’s an expensive investment and one that pays to learn how to handle properly. They work well without needing a mainsail set and are increasingly popular with multihull owners.

How they work and the different types available – Istec’s Parasail and Parasailor, Wingaker and Oxley – is another whole article.

Lagoon 450F Marlove was one of 44 parasailer users last ARC, flying theirs for 13 days and nights: “made our life easy, perfect sail to cross the Atlantic”. Another Lagoon, Rockhopper of London , agreed, calling it a ‘hoist and forget’ sail: “no trimming – the sail coped well with wind shifts”. And Ovni 385 Contigo reports: “Parasail is amazing up to 20 knots and easy to snuff if the wind got too high.”

The Harpers on their two-year-old Jeanneau Yachts 51 Blue Pepper spent a season using their parasailer to prepare: “We practiced all the configurations we used several times as a crew before we got to the Canaries – it paid off. The Parasailor was excellent, stable, including in gusts, and very easy to manage. Twin headsails also worked well and were surprisingly powerful, but Parasailor is faster, easier, with less wear and tear on running rigging.”

Fountaine Pajot Saba 50 Lady Roslyn exhibits all 190m2 of her bright red P16 model Wingaker. Photo: Wingaker

Those with parasailers seemed happier to keep them up at night. The skipper of Lagoon Cosi mentioned how he would sleep in the cockpit for this. However, several others added caution about getting a parasailer down – the wing element can makes snuffing tricky, confirmed by the double-handed crew on Broadblue Rapier 550 Blue Wonder . Hence others promote snuffing parasailers early, including Galatea Of Aune , who tore theirs in a squall.

Of the 44 international skippers who shipped parasailers it’s hard to know exactly which types they had as many just list them as ‘parasailer’, but there were clearly some staunch supporters of both Oxley and Wingaker types. “Oxley is amazing! Very stable, very flexible in terms of wind strengths (gusts and wind direction),” reckon the Dutch crew on their Garcia Exploration 60 Fiore .

The Swiss crew on Moody 54DS Nautilia were equally impressed: “We used it up to gusts until about 24 knots – gives calm downwind sailing with good speed.” The Bösch’s on Jeanneau 51 Wolkenschlosschen said their Levante “worked really well,” using it 90% of the time, adding “take Oxley down below 20 knots TWS and use it in gennaker mode”.

Aussie-flagged Fountaine Pajot 40 Cat’s Pajamas flew their 130m2 Oxley for 16 days and, other than advising to get it down early for squalls, the only thing they’d change is to get a larger version.

Oxley offers the Levante (for up to 20 knots) and the flatter Bora with an inflatable double-layer wing for higher winds, seas and gust damping.

More Oxley fans on the Garcia Exploration 60 Fiore. Photo: Harmen-Jan Geerts/Fiore

“The new Bora was excellent,” reports Oyster 55 Valent, although they still found it difficult to snuff once the wind was over 14 knots.

The main difference the Wingaker has over other parasailers is that it is a single construction including the vent and wing, which it claims produces a more stable performance and is easier to handle and crucially to snuff. The feedback for it was equally praiseworthy, particularly from catamaran owners.

The new Seawind 1600 cat Pure Joy thought it just that: “Wingaker very easy to handle and gybe as well as sail completely downwind.” The American crew on FP Aura 51 Darla J left a strong testament: “2,142 miles without taking the Wingaker down”. And the Kiwi FP Elba 45 Aratui simply stated: “Take a Wingaker” after flying theirs for 90% of the voyage including at night.

More multihull solutions

Multihulls offer great platforms for experimenting with downwind setups. While it’s easy to picture a cat flying along on a flat reach under screecher or A-sail, running downwind brings questions on how best to fill the slots in different wind strengths. Indeed the Canadians on their new Nautitech 44 Open June asked for “more detail on catamaran downwind strategy in the ARC’s downwind seminar”. They found “full main and gennaker faster than Oxley but poor below 150° TWA – Oxley backs wind behind main”. They wished for a better solution for between 18-24 knots wind.

The family dream? Letting the parasailer do the work on June, a Canadian Nautitech 44 Open. Photo: Peter Hunt/June/WCC

Portuguese FP Tanna 47 Portlish found a good combination between gennaker (with furler) and parasailer. “Gennaker was used for 110°-160° AWA and also during the night, parasailer for 160°-180°.” However, they advised it’s not easy without a pole: “We would add a spinnaker pole to be able to use a poled-out genoa for downwind sailing in above 25 knots of wind.”

The 53ft bluewater catamaran Lost Abbey favoured goosewinging either their spinnaker, asymmetrical or screecher with the genoa, but still would have liked a parasailer. Norwegian RCC Majestic 530 Tempus seconded this: “If money were no object I’d buy a parasailer.” Instead, they mostly used “the asymmetric spinnaker on either bow plus one to two reefs in main”.

FP Lucia 40 Wanderlust used a Code 0 and asymmetric the most: “both behaved well downwind and sometimes we flew both side-by-side”. They caution: “big mainsails and booms are a pain downwind!” While the new Excess 15 Vida Loca adds: “as the rig required the mainsail to be flown with the gennaker, our sailing angles in decent wind were 160° AWA”.

Nautitech 46 Open Pinnacle found their most effective sailplan to be: “TradeWind with third reef, next asymmetric with third reef – downwind sails need less mainsail in the less wind,” they warn after they had problems with their snuffer twisting. The sail lashing at the head of the TradeWind also chafed through, tearing the sail as it came down. Which leads us to other sail handling problems…

Sewing sail repairs on the Contest 50CS Athena. Photo: Philip Mrosk/Athena/WCC

Problems & repairs

Having your ideal sailplan is one thing, but what do you do when that breaks? The majority of ARC skippers experienced failures with sails and their handling, mostly with tears they needed to repair, and the overriding advice is to carry plenty of tape and patches, a sewing machine if possible, an extensive sewing kit if not.

“With a good sail repair kit a sail can always be repaired,” the crew on Penny Oyster advise. Grand Soleil 46LC Mandalay suffered a torn clew and luff in their headsail and a torn batten pocket in the main, but report all were “hand stitched or taped and held OK”. After the A-sail “ripped from leech to luff” on the new Oyster 595 JaZoFi, the crew stitched and taped the 12.5m tear, “but only had a 25m roll of 50mm tape”. Frustratingly, the repair only lasted an hour.

Chafe to sheets and halyards is the other biggest issue on long downwind passages. “We had chafing on pole ends caused by metal eyes on sheets,” Jeanneau Sunshine 38 Cloud Jumper warns. “We failed to use plastic balls to prevent damage until too late.”

There were also a large number of halyard failures last year, including two spinnaker halyards and the genoa halyard on the Alloy Yachts Irelanda alone.

Amel 60 Mrs G and Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 44 Moyfrid both snapped gennaker halyards: “the halyard fell down inside the mast – unable to retrieve it while underway,” Moyfrid bemoans. “Carry spare halyards to replace any that chafe or break,” is Hermione III’s advice.

Final thoughts

Having compiled this survey for over 15 years, it’s clear to see that ARC yachts are getting newer and larger and their owners are increasingly happy to spend that bit extra to get the best out of their yachts or find their ideal sailplan.

Today’s easily set and handled Code sails and asymmetrics offer a completely transformative experience during most of the test sails I do on these new boats. But for a tradewind passage I’d choose a specialist downwind sail, budget and space willing, and/or make sure I had a pole and headsail large enough to goosewing effectively.

Know your sails’ limits (in wind and waves) and what you would default to over certain strengths, remembering that tradewinds can be strong for days and nights at a time.

Then get comfortable with your downwind setup so all crew can safely manage and ideally reef it short-handed, identify chafe points in advance, and have a backup plan including spares and repairs.

Your dream crossing should be just that, so take the stress out in advance if you can – and enjoy the ride!

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams. Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Sailing Terms: A Complete Guide

Last Updated by

June 15, 2022

Learning sailing terms when you first get into boating can be a daunting task.

Some sailing terms are logical, like 'fore' means forward or front of the boat, while others might as well be in a different language. Athwartship, for example. Nothing in our daily lexicon gives any clues as to what that might mean. Like it or not, it's time to dust off the old noodle and get to memorizing some new vocab words!

Knowing the difference between a clew and a tack, a luff and a leech, will help you communicate with your sail maker regarding which part of your sail needs resewn. If you need to have your rigging adjusted, you must know the difference between your shrouds and your stays, your standing rigging vs. your running rigging.

By educating yourself in the correct names of all parts of your sailboat, you can avoid situations in which you may need to use terms such as ‘thingy’ or ‘that round part at the end of that thing’. While even the most seasoned sailor occasionally troops over the vernacular, it is always beneficial to have as wide a nautical vocabulary as possible. Many in the sailing community get by without knowing the entire sailing dictionary, but if you’re interested in avoiding vocabulary embarrassment, check out the list I’ve compiled of sailing terms that every sailor ought to know.

I’ve been sailing on and off throughout my life and I know from experience that it is incredibly helpful to know the correct terms for each part of your sails, rigging, and boat.

Sailors are among the kindest, most helpful people you’ll ever meet. But, if you’re looking for help on why you’re not getting the most speed out of your mainsail and you know don’t know the correct terms for each part of the sail, it may be hard to get advice from you fellow sailor on why ‘the back of the mainsail is flappy’. They would be more likely to give useful advice if you’re able to tell them that you’re struggling to keep wind in the roach of your mainsail. Check out my list of sailing terms and see if a few don’t stick. I’ve done my best to include pictures when possible.

Table of contents

Sailing Terms

Abeam : When an object, craft or island is abeam your vessel, that means that it is off the side of your boat. It is 90 degrees from the centerline of your boat.

Abaft : Toward the stern. “Honey, have you seen my boat shoes?” “They’re abaft the navigation table!” This is the opposite of forward.

Aft : In the stern of the boat. For example, the back cabin is referred to as the aft cabin.

Apparent wind : The wind direction and speed which the crew observes to be blowing in combination with the true wind. This is often different from the true wind direction and speed due to the boat's motion.

Astern : The area behind the boat. If you go astern, you are going in reverse.

Athwartship : Directionally perpendicular to the centerline of the boat.

Backing (a sail) : Forcing the sail to take wind into its opposite side by pulling the sail to the opposite side of the boat.

Backstay : The wire that runs from the back of the boat to the mast head. This prevents the mast from falling forward.

Bailer : Any scoop-like container that is used to remove water from within a vessel’s hull.

Ballast : Weight which adds stability to the vessel. The weight usually is composed of lead or iron and placed low in the boat's hull, such as within the keel.

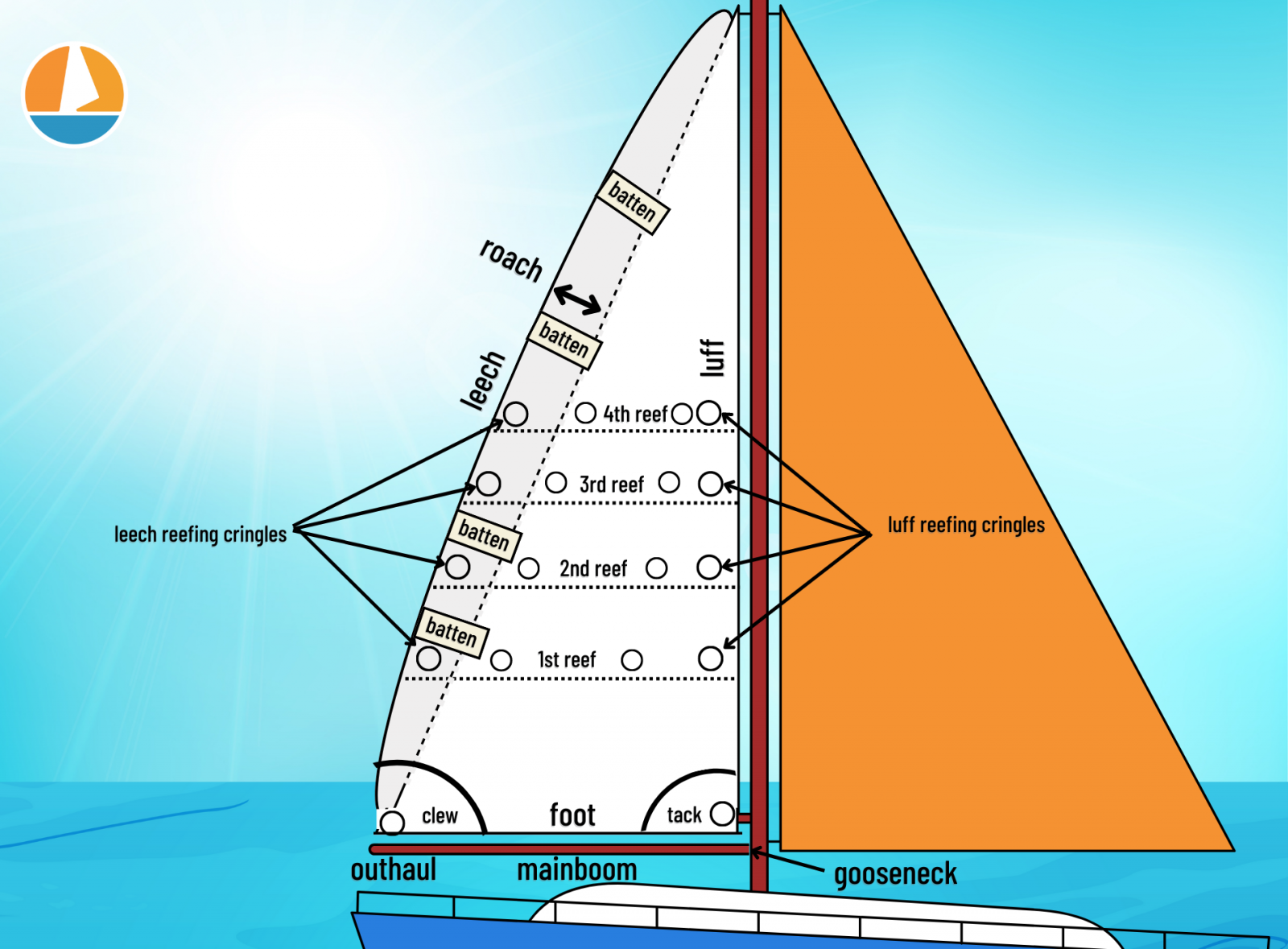

Batten : a thin, flexible strip (often fiberglass) that is inserted into the main sail to help it stay open to the wind. The batten runs from the back edge of the sail (leech) toward the front edge (luff).

Beam : The width of the vessel at its widest point.

Beam reach : Sailing with the wind blowing perpendicular to the direction the boat is traveling.

Bearing off or Bearing away : Steering the boat away from the direction in which the wind is blowing.

Bend : a knot which connects two ropes.

Berth : A slip, a mooring, or a bed within the boat.

Bight : A bend or loop in a rope. When a rope forms a bight, it has changed direction 180 degrees.

Bilge : The lowest area within a boats hull. This area collects water which is then pumped overboard by a bilge pump.

Bimini : The covering over the cockpit. Usually constructed from a stainless steel frame covered with canvas or fiberglass. It provides protection from sun and rain, but not wind.

Binnacle : The pedestal centrally located in the cockpit that generally holds the steering wheel and navigational instruments.

Block : A pulley.

Boom : This pole runs perpendicular to the mast and holds the bottom of the mainsail in place. Its position is adjustable side to side as needed for the wind direction.

Boom vang : A tackle which ensures that the boom does not lift upward from wind pressure in the mainsail.

Boot Top or Boot Stripe : The stripe of tape or paint between the boat's underwater (bottom) paint and it’s above water (topside) paint.

Bow : Front end of the boat

Bowsprit : The forward most protruding pole or platform which some boats possess. This spar allows for the sails and rigging to be attached further forward.

Broach : When a boat sailing downwind accidentally ends up sideways to the waves and heels over dangerously. This can be caused by large seas or poor steering.

Broad reach : Sailing with the wind coming off your stern quarter. If you’re standing at the helm facing the bow, the wind is blowing halfway between the side and the back of the boat.

Bulkhead : The walls in a boat which run athwartship, or perpendicular to the centerline of the vessel.

Capsize : When a vessel tips over past 90 degrees.

Catamaran : A vessel with two hulls.

Centerboard : A retractable keel which helps the sailboat maintain course and stability underway. When raised, the vessel is able to enter shallow waters.

Centerline : An imaginary line that runs from the center of the bow to the center of the stern.

Chainplate : A metal plate that is secured to the boat's hull to which wires supporting the mast are attached. The chainplates may be exterior or interior, visible or hidden.

Chandlery : A store that sells boat supplies and parts.

Cleats : The wooden or metal piece to which ropes are secured.

Chock : A fitting that a line passes through to change direction without chafing.

Clew : The lower back corner of a sail. This is where the foot and leech of the sail meet.

Close-hauled : Sailing as close to the direction the wind is coming from as possible with the sails pulled in tight. (See Points of Sail for infographic.)

Close Reach : Sailing between close hauled and beam reach. (See Points of Sail for infographic.)

Coamings : The lip around a hatch or window which stops water from entering. Also the raised area around the cockpit to keep out water.

Cockpit : The area from which steering occurs. This can be in the center of the boat or in the back of the boat.

Companionway : The doorway into the cabin.

Cotter pin : a bendable metal pin which is inserted into a metal rod then bent to lock it in place.

Daybeacons : Markers for navigation which are on posts. These are red or green.

Dead run : Sailing with the wind coming from directly behind the boat. Sails are fully out to catch the wind.

Dead reckoning : Determining a vessel's position by knowing the direction and speed traveled.

Dinghy : A small boat which is used to travel to shore from the main vessel. This can be propelled oars or a motor.

Dodger : The structure at the front of the cockpit which protects the cockpit and companionway from wind and spray. This is generally made of stainless steel frame covered with canvas and plastic windows. It can also be a solid structure with solid windows.

Dismasting : When the mast breaks off the boat. This can occur due to rigging failure or structural failure of the mast.

Displacement : The weight of the water that would otherwise be in the place of the boats hull.

Drogue : A sea anchor which is deployed to help control the drift of a vessel. It can be constructed like a parachute, bucket, or even a rope dragging behind the boat.

Ebb tide : After high tide when the water is receding towards low tide.

EPIRB : Stands for Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon. This device transmits a distress signal to emergency services and notifies them of a vessel's location.

Fairlead: A fitting which encloses a line within a smooth ring and helps guide its direction.

Fathom : A measurement of water depth equal to 6 feet.

Fid : A pointed tool used when splicing a line.

Fiddle : The raised edge around a table which prevents objects from falling off as the boat rocks or heels.

Fix : Determining a vessel's location by using the compass bearing of two or more fixed points of reference such as landmarks or buoys.

Fin keel : A fixed, ballasted keel which is centrally located beneath the hull. It does not run the full length of the hull.

Flogging : When a sail flaps noisily because it is not being filled by the wind.

Flood tide : Time period between low tide and high tide when the water is rising.

Foot : The bottom edge of a sail.

Fore : At or near the bow of a vessel.

Forestay : The wire which leads from the bow to the top of the mast. The forward most sail attaches to the forestay either directly or by use of a roller furling system.

Full keel : A fixed, ballasted keel which runs the full length of the hull.

Furling system : A system around which the sail wraps when not in use and is unwrapped for sailing. This may be around the forestay or within the mast.

Freeboard : The distance on a vessel from the waterline to the deck.

Galley : The kitchen on a boat.

Gelcoat : A colored resin which is painted onto the outside surface of a boat and forms a protective glossy layer.

Genoa : A large forward sail which, when fully extended, comes back past the mast. Larger than a jib sail.

Gimbals : Often attached to a boat's stove, it is the fitting which allows an object to maintain an upright position when a vessel heels.

Gooseneck : The point at which the boom attaches to the mast. It allows the boom to move in all directions.

Ground tackle : The anchor, chain, and line used to fix a boat to the bottom when anchoring.

Gunwale : Pronounced “gunnel”. This is the top edge of a boat's hull.

Halyard : The line which attaches to a sail to raise it.

Hanks : The clips that attach the front edge (luff) of a sail to the forestay.

Hatch : An opening window in the cabin roof much like a skylight.

Head : Bathroom on a boat. Also, the uppermost corner on a sail.

Headway : The forward motion of a vessel through the water.

Heave to : A method of controlling a boat’s position to the waves and limiting headway by backwinding the forward sail and keeping the rudder hard over into the wind.

Heel : The tilt that occurs to a boat's hull when the sails are filled with wind.

In-Irons : When a sailboat is bow into the wind with sails flapping. No steerage is possible as the vessel has no forward motion. (See Points of Sail for infographic.)

Jackline or Jackstay : Lines that are run from the bow to the stern. To these safety lines, sailors attach a lanyard connected to their harness so that they may work on deck without fear of being swept overboard in rough seas.

Jib : A triangular forward sail.

Jib sheets : Lines used to control the jib.

Jibing : Pronounced with a long i sound. Steering the boat from one downwind direction to another downwind direction by turning the stern of the boat through the wind. This will cause the sails to move across the boat to the other side, i.e. from port to starboard.

Kedge anchor : A small, lighter second anchor.

Keel : The bottom most part of a boat's structure. This part provides ballast and stability.

Ketch : A sailboat with two masts. The forward mast is the taller mast.

Knot : Regarding speed, one knot is equal to one nautical mile per hour.

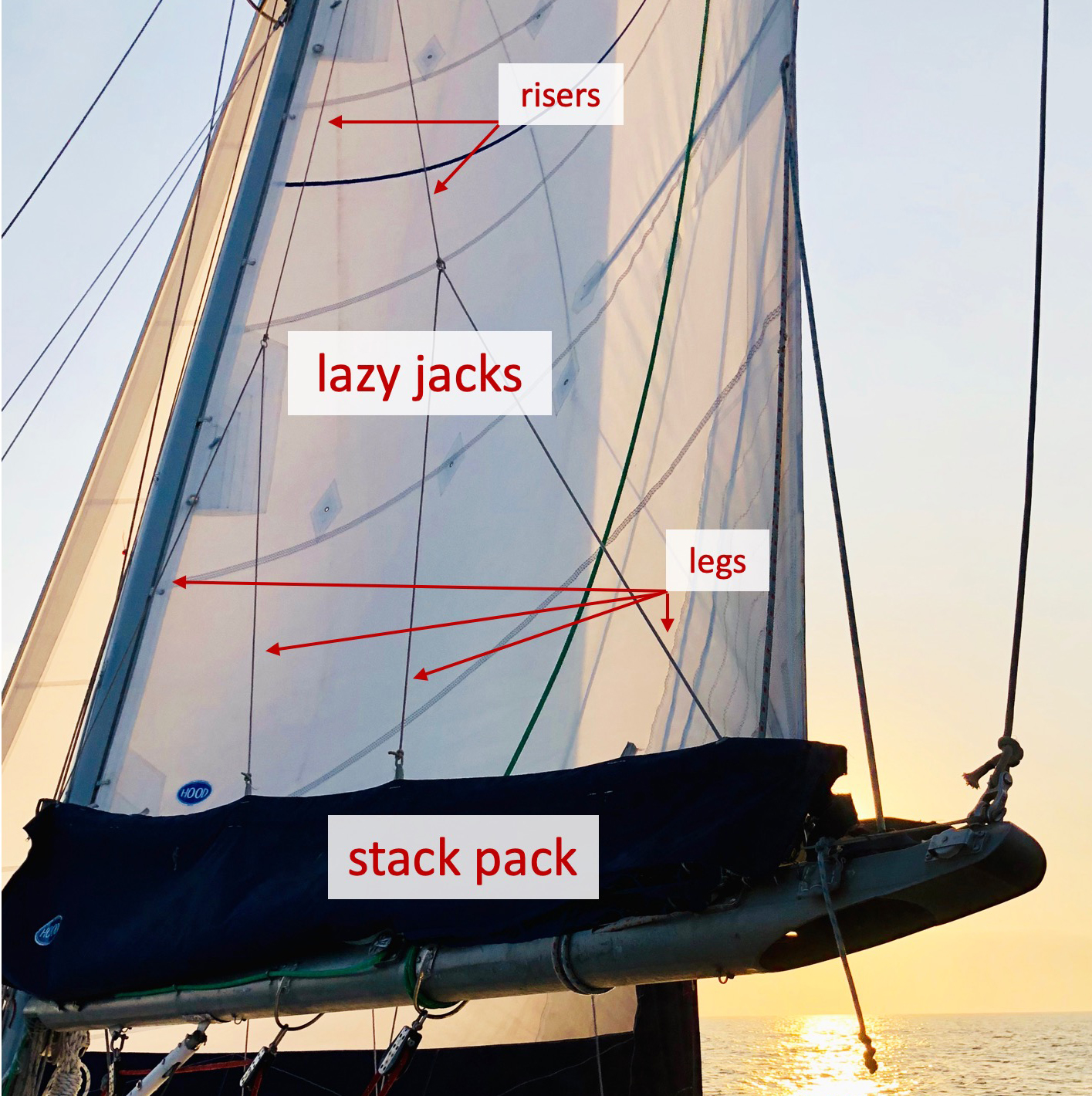

Lazyjacks : Light lines that run from the boom to the mast and help contain the mainsail while it’s being lowered to the boom.

Leech : The back edge of a sail. If the sail is square, then this term refers to the outside edges of the sail.

Lee shore : The shore onto which the wind is blowing. On an island, the side of the island facing into the wind is the lee shore.

Leeward : The direction to which the wind is blowing. If the wind is coming from the north, then south is leeward.

Luff : The forward edge of the sail.

Lying a-hull : When a vessel is drifting with all of it’s sails down.

Mainsail : Pronounce main’sil. The primary sail of a boat that is hoisted up or unfurled from the mast.

Mayday : An emergency call put out over a marine radio when there is clear and present danger to the crew of the vessel.

Mizzen : The shorter mast behind the main mast on a ketch.

Monohull : A vessel with a single hull.

Mooring field : An anchorage in which permanently anchored buoys are present to which vessels may be secured.

Multihull : A vessel with more than one hull such as a catamaran or trimaran.

No-sail zone : This is an area 45 degrees to either side of directly into the wind. It is not possible for a boat to sail in this zone as the sails cannot fill with wind. Tacking is necessary. (See Points of Sail for infographic.)

On the hard : When a vessel is out of the water and being stored on land.

Painter : The line which secures the bow of a dinghy to the main boat.

Pan Pan : Pronounced pon-pon. This is an urgent distress radio call which is used when a vessel needs assistance. It is one step below Mayday.

Points of sail : The vessels course in relation to the direction of the wind.

Port : The left side of the boat when facing forward.

Port tack : Sailing with the wind hitting the port side of the vessel and the sails are out on the starboard side.

Pulpit : The metal rails at the bow of the boat which protect the crew from going overboard.

Pushpit : The metal rails at the back of the boat to protect the crew from going overboard.

Quarter : The back corner area of the boat. This area is 45 degrees behind, or abaft, the beam of the vessel.

Reef : reducing the size of the sail in high winds for the safety of the crew and equipment. This is done by either tying or rolling the sail to the boom or forestay.

Rigging : All the wires and ropes used to hold the mast in place and adjust the sails.

Roach : The outer back edge area of the mainsail. If you were to draw a diagonal line from the head of the sail to the clew (back corner), the roach would be outside this diagonal line.

Roller furling : A system which rolls the sail up when not in use. The sail is stored on the roller either at the mast or boom for the mainsail, and at the forestay for the jib or genoa.

Rudder : Steering fin at the back of the boat. Controlled by a steering wheel or tiller from the cockpit.

Running : Sailing in a downwind direction.

Running rigging : The lines, such as sheets and halyards, which control the sails.

Schooner : A sailing vessel with two or more masts. The mainmast is at the back.

Seacock : a valve which can be open or closed to allow water to flow in or out of a through hull fitting.

Scope : The length of chain and line that is between the anchor and the boat.

Scuppers : Deck drains which allow water to flow overboard.

Securite : Pronounced securi-tay. This is a radio call to provide mariners with local marine safety information.

Shackle : A metal U or D shaped link which has a removable pin through the ends.

Sheet : A line or rope which connects to the clew (back corner) of a sail. It is used to control or trim the sail.

Shrouds : Wires or ropes which run from the deck chainplates to the mast. The shrouds prevent the mast from moving side to side.

Skeg : A section of the hull from which the rudder hangs. It provides a variable amount of protection to the rudder depending on its size.

Sloop : A single masted sailboat with a mainsail and a foresail.

Slugs : Fittings on the front edge (luff) of the mainsail that slide into the mast track for hoisting the sail.

Spinnaker : A large, light, often colorful sail that is used off the bow of the boat for sailing downwind (running).

Splice : Connecting two lines together by weaving their strands together.

Spreaders : The horizontal arms extending out from the sides of the mast.

Spring line : Dock lines positioned from the bow to a midship point on the dock or from the stern to a midship point on the dock. This line configuration helps decrease forward and backward motion of the boat while docked.

Stanchions : The metal posts along the outside edge of the deck through which the lifelines run.

Standing rigging : The wires and ropes, such as the shrouds and stays, that are permanently in place and hold up the mast.

Starboard : The right side of the boat when facing forward.

Starboard tack : Sailing with the wind hitting the starboard side of the boat and the sails out on the port side.

Stays : The wires or ropes which run from the bow and stern to the mast top to keep the mast from moving forward or backward.

Steerage way : When a vessel is moving through the water with enough speed to allow the rudder to steer the boat.

Stern : The back end of a boat.

Storm jib : A small, strong forward sail used in heavy winds.

Swing : The circular motion of an anchored boat around it’s anchor due to wind and water movement.

Tack : The forward lower corner of a sail.

Tacking : Turning the boat across the direction the wind is coming from to change course direction. This causes the sails to travel to the other side of the boat.

Tender : Small boat used to transport from shore to the main boat.

Tiller : A bar which controls the rudder and is used to steer the boat from the cockpit. It is used in place of a steering wheel.

Toe rail : The raised lip around the edge of the deck. This can be constructed of wood, fiberglass, or aluminum. It helps prevent items from rolling overboard.

Topping lift : A wire or rope which runs from the back end of the boom to the mast top. This line controls the height of the boom.

Trysail : A small, strong storm sail that is used in place of the mainsail in high winds.

Trim : To adjust the sails.

Winch : A round, drum-like mechanical device used to pull on a line to raise or adjust sails.

Windlass : A winch used to raise and lower the anchor.

Windward : The direction from which the wind is blowing.

Wing on wing : Sailing downwind with the mainsail out on one side and the foresail on the opposite side.

Related Articles

Beth lives on board her 1983 30ft S2 sailboat with her husband, 6 year-old son, and her two fur babies. She has been sailing and boating for most of her life. Beth has been blessed to experience cruising in the Great Lakes, the Bahamas, and in Alaska. She loves to travel and adores living on her tiny boat with her family.

by this author

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

Daniel Wade

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

How To Choose The Right Sailing Instructor

August 16, 2023

Cost To Sail Around The World

May 16, 2023

Small Sailboat Sizes: A Complete Guide

October 30, 2022

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

Everything you need to know about Changing Sails on your Sailboat

Table of Contents

Step by Step Guide on How to Change Sails on a Sailboat

Changing damaged sails on a sailboat can be a daunting task, but with the right tools and knowledge, it can be done quickly and efficiently. In this blog post, we will go over the step-by-step process of changing damaged sails on a sailboat.

Step 1: Gather the necessary tools and materials Before you begin, make sure you have all the necessary tools and materials. This includes a new sail, sail repair tape, scissors, a needle and thread, and a sail repair manual.

Step 2: Remove the damaged sail To remove the damaged sail, first, lower the sail using the halyard and then remove the sail from the sailboat. Take care to fold the sail properly to prevent further damage.

Step 3: Inspect the sail Once the sail is removed, lay it out flat on a clean surface and inspect it for any tears or holes. Mark the damaged areas with a pen or marker.

Step 4: Repair the sail Using the sail repair tape, patch up any small holes or tears in the sail. For larger holes or tears, use a needle and thread to sew the sail back together. Make sure to use a strong thread that is the same color as the sail.

Step 5: Reinforce the sail To reinforce the sail and prevent future damage, use sail repair tape to create a patch around the area that was repaired. This will provide extra support and make the sail stronger.

Step 6: Reinstall the sail Once the sail has been repaired, it’s time to reinstall it on the sailboat. Start by attaching the sail to the mast using the halyard. Next, attach the sail to the boom using the outhaul and the downhaul. Finally, adjust the sail to the proper shape and tension.

Step 7: Test the sail Once the sail is installed, take the sailboat out for a test sail. Make sure the sail is properly adjusted and that there are no further issues.

Changing damaged sails on a sailboat can be a time-consuming task, but with the right tools and knowledge, it can be done quickly and efficiently. By following these steps, you can ensure that your sailboat is ready to hit the water again in no time.

Note: This is a general guidance and it’s always best to consult the manufacturer’s manual and/or consult a professional sailor or sail repair specialist if you are not sure of something.

Is it time to replace/maintain my sails?

One of the most important parts of maintaining your boat is keeping an eye on your sails and knowing when it’s time to replace or repair them.

One of the first signs that your sails may need to be replaced or repaired is if they begin to show signs of wear and tear, such as frayed edges, holes, or tears. These signs can be caused by a variety of factors, including exposure to the sun, wind, and water, as well as improper use or storage. It is important to inspect your sails regularly and address any issues as soon as they arise to prevent further damage.

Another sign that your sails may need to be replaced or repaired is if they are no longer able to hold their shape or maintain proper tension. This can be caused by a variety of factors, including stretching, shrinkage, or damage to the material. If your sails are no longer able to hold their shape, it can make it difficult to control your boat and can also increase the risk of capsizing.

If you notice any signs of wear and tear or damage to your sails, it’s important to address the issue as soon as possible. This may involve repairing or patching small holes or tears, or replacing your sails entirely. It is also important to take proper care of your sails by storing them in a dry, cool place and making sure that they are properly cleaned and maintained.

In summary, the key to maintaining your sails and ensuring that your boat is in good condition is to keep an eye on the condition of your sails and address any issues as soon as they arise.

Pros and Cons of Repairing/Replacing Damages Sails

| – Cost-effective | – Can provide a new and improved sail with updated materials and technology |

| – Can be done quickly and easily with the right tools and knowledge | – Can improve overall performance and efficiency of the sailboat |

| – Saves the environment by not disposing of the sail | – Can provide a fresh and new look to the sailboat |

| – May not be as strong or durable as a new sail | – Can be expensive |

| – May not provide the same level of performance as a new sail | – May not be the most environmentally friendly option |

| – Repaired areas may be visible | – May require more time and effort to install |

Please note that this is a general table and the pros and cons may vary depending on the specific situation and the type of sail.

Where to buy new sails

There are a variety of places where you can buy new sails for a sailboat. Some options include:

- Sailmakers and sail lofts: Many sailmakers and sail lofts specialize in creating custom sails for sailboats. They can create sails tailored to your specific needs and preferences.

- Marine supply stores: Many marine supply stores carry a wide range of sails, including replacement sails for specific sailboat models.

- Online retailers: You can also purchase new sails online from a variety of retailers. Some popular online sail retailers include Sailrite, US Sailmakers, and North Sails.

- Sailboat manufacturers: Many sailboat manufacturers also sell replacement sails for their specific models.

- Sailboat dealers: Some sailboat dealers also carry replacement sails for the sailboats they sell.

When buying a new sail, it’s important to consider factors such as size, material, and intended use. It’s also a good idea to consult with a professional sailor or sail repair specialist to ensure that you get the right sail for your sailboat.

Tips of how to choose which sail to buy

When choosing a new sail for your sailboat, there are a few key factors to consider:

- Size: Make sure the sail you choose is the right size for your sailboat. The size of the sail is determined by its luff, leech, and foot measurements.

- Material: The choice of material for your sail will depend on the intended use of the sailboat. Dacron is a popular and durable material for cruising sails, while laminate materials like Mylar or Kevlar are used for racing sails because they are lightweight and strong.

- Shape: The shape of the sail will also affect its performance. Full-batten mainsails and roller furling headsails are popular options for cruising sailboats, while racing sailboats often use a square-top main and a jib with a smaller roach.

- Intended use: Consider the type of sailing you will be doing and choose a sail that is suitable for that purpose. For example, if you will be doing a lot of racing, a high-performance racing sail would be a good choice.

- Brand reputation : Look for sailmakers that have a good reputation and a track record of producing high-quality sails.

- Price: Finally, consider the cost of the sail, and compare it to the other options available.

It’s always a good idea to consult with a professional sailors or sail repair specialist to ensure that you get the right sail for your sailboat. They can provide expert advice and help you choose the best sail for your specific needs and preferences.

How important is a Sail on a Sailboat

Sails are extremely important on a sailboat as they are the primary means of propulsion. A sailboat’s ability to move through the water is dependent on the wind and the sails’ ability to harness that wind energy and convert it into forward motion. Sails are also an important safety feature as they can be used to control the direction and speed of the boat, which can be crucial in emergency situations.

A well-designed and properly maintained sail can also greatly affect the performance and efficiency of a sailboat. The right sail can help a sailboat reach its maximum speed and maneuverability, making sailing more enjoyable and efficient.

Additionally, sails are an important part of the aesthetics of a sailboat, and a new or well-maintained sail can give a sailboat a sleek and polished look.

In summary, sails are crucial for the propulsion, safety, performance, and aesthetics of a sailboat. Proper maintenance and care of the sails are crucial for the sailboat to function properly and safely.

Are there designer brands of sails?

Yes, there are designer brands of sails available. These are typically high-end sail manufacturers that are known for producing high-quality and innovative sails for sailboats. These brands are often associated with performance, technology, and design and have a reputation for producing top-performing sails that are made with the latest materials and manufacturing techniques.

Examples of designer sail brands include:

North Sails

Doyle sails, quantum sails, uk sailmakers.

Ullman Sails

These brands have a reputation for producing high-quality and high-performing sails that are made with the latest materials and manufacturing techniques. They can be more expensive than other sails, but they offer many advantages, such as better performance, longer lifespan, and a unique look. It’s always a good idea to consult with a professional sailors or sail repair specialist to ensure that you get the right sail for your sailboat.

Do you need necessarily a specialist to change a sail for you?

You do not necessarily need a specialist to change a sail on your sailboat. However, it can be helpful to have the assistance of someone who has experience in working with sails, as they will have the knowledge and skills needed to properly measure and install the new sail. Changing a sail can be a complex task that involves working with ropes, pulleys, and other hardware, as well as dealing with wind and weather conditions. Additionally, it’s a task that requires attention to detail and the ability to work in confined spaces.

If you are not familiar with sail handling, rigging and maintenance, it is recommended to seek the help of a professional sail maker or sail repair specialist. They can also help you to choose the right sail for your boat and your needs, and will be able to repair or replace your sails with the right technique and materials.

If you choose to change the sail yourself, make sure to read the instructions carefully and practice safety precautions. Always wear protective gear, such as gloves and goggles, and never work alone. If you are not confident in your abilities, it’s best to seek the help of a professional.

Which type of sails are the most difficult to change

Some types of sails are more difficult to change than others, depending on the design and construction of the sail, as well as the type of boat it is used on. Some of the most difficult sails to change include:

- Mainsails: The mainsail is the largest sail on a sailboat and is typically the most difficult sail to change. It is attached to the mast and boom, and can be difficult to remove and replace due to its size and weight. Additionally, the mainsail is often used to control the speed and direction of the boat, so it is important to ensure that it is properly adjusted and tensioned.

- Spinnakers: Spinnakers are large, balloon-shaped sails that are typically used for downwind sailing. They can be difficult to change because they are often used in conjunction with other sails, such as the jib or genoa, and require coordination between the crew. Additionally, spinnakers are typically made of lightweight and delicate materials, which can be easily damaged if not handled properly.

- Gennakers: Gennakers are similar to spinnakers and are used for downwind sailing, but are more user-friendly and are typically easier to handle and change.

- Square-rigged sails: Square-rigged sails are typically used on larger, traditional sailing vessels and can be difficult to change due to their size and complexity. They are typically made of heavy materials and require a large crew to handle them.

It’s important to note that changing any sail requires a certain level of skill and experience, and it’s always best to consult with a sail repair specialist or professional sailors to ensure that you get the right sail for your sailboat.

Which type of sails are the easiest to change?

Some types of sails are generally considered to be easier to change than others, depending on the design and construction of the sail, as well as the type of boat it is used on. Some of the easiest sails to change include:

- Jibs: Jibs are triangular sails that are located at the front of a sailboat and are typically the easiest sail to change. They are smaller in size compared to other sails and are relatively easy to handle and replace.

- Genoas: Genoas are similar to jibs but are larger and are typically used in conjunction with the main sail. They are also relatively easy to change, but may require more skill and experience than a jib.

- Roller-furling sails: Roller-furling sails are sails that are designed to be easily rolled up and unrolled, making them easy to change. They are typically used on smaller sailboats and are a popular option for sailors who are looking for a more user-friendly sail.

- Dacron sails: Dacron is a type of synthetic fabric that is commonly used in sailmaking. Sails made of Dacron are relatively easy to change, as they are strong and durable, but not as expensive as other types of sails.

In conclusion, changing sails on your sailboat can seem like a daunting task, but with the right knowledge and preparation, it can be a smooth and enjoyable process. Remember to assess the damage on your current sail, consider the pros and cons of repairing versus buying a new one, choose the right replacement sail, and consult with a sail repair specialist or professional sailor for guidance. Additionally, be aware of different sail manufacturer brands, the average prices and durability estimation.

In this blog post, we’ve provided you with a step-by-step guide on how to change sails on your sailboat, as well as tips on choosing the right sail and information on popular sail manufacturers. By following the information provided in this post, you’ll be able to change your sails with confidence and get back to enjoying your time on the water.

Steven T. Anderson

Steven Taylor Anderson is an experienced sailor and author who writes for sailingbetter.com. He has been sailing for over 20 years across the USA and has taken several courses to improve his skills. He has also navigated throughout the world on various boats and yachts. His passion for sailing and knowledge of the sport shines through in his writing, making him a respected authority on the subject.

Recent Posts

Lagoon vs Leopard Catamaran: Which Sailboat Is Right for You?

Introduction When it comes to cruising on the open waters, catamarans have gained immense popularity for their stability, space, and comfort. Two of the leading catamaran manufacturers, Lagoon and...

How to Determine Sailboat Weight: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction Sailing is a thrilling and adventurous activity that has captivated humans for centuries. Whether you are a seasoned sailor or a novice looking to set sail for the first time,...

The 6 Points of Sail: An Illustrated Guide

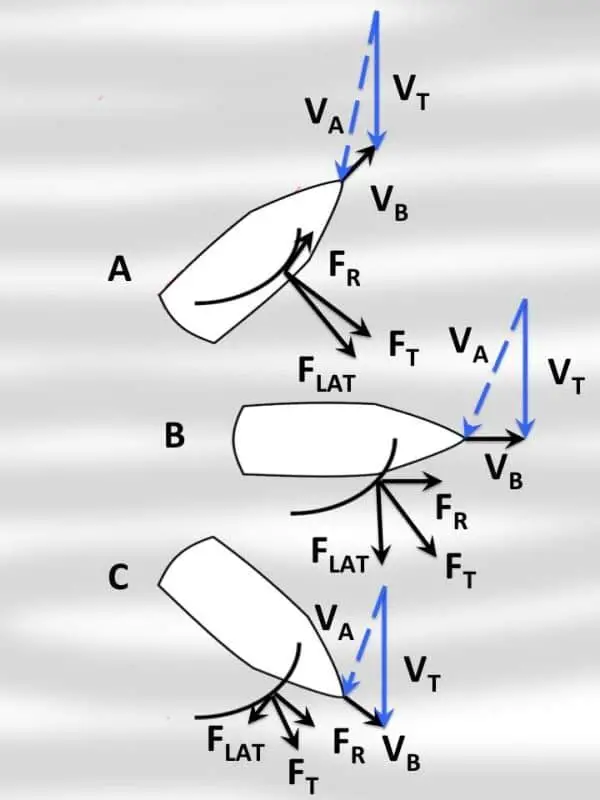

Depending on the direction of the wind and where you’d like to take your sailboat, you’ll need to consider which point of sail to be in. Whether you’re sailing upwind (windward) or sailing downwind (leeward), your sails will either take on the characteristics of an airplane wing or a parachute.

So what are the points of sail on a sailboat? The points of sail include into the wind (in irons), close hauled, close reach, beam reach, broad reach, and running, which go from windward to leeward and are all symmetric from port to starboard.

Knowing the points of sail on a sailboat is important in terms of being knowledgeable about how your sailboat generates wind power while also being able to properly communicate with your crew.

It’s also important to understand the difference between upwind sailing and downwind sailing.

There’s a lot of sailing terminology to hash out here as well, so let’s dive into all the different points of sail and learn what they all really mean.

Points of Sail

A point of sail is the direction of a sailboat’s journey while taking into consideration the direction of the true wind as opposed to apparent wind.

The difference between true wind and apparent wind is that true wind is the wind that’s felt by something or someone in one place (like on land) while apparent wind is the wind felt when on the move (like on a sailboat).

The points of sail, when combined, complete a full 360 degrees. Starting from the top (0 degrees) all the way to the bottom (180 degrees), we’ll now explore the different points of sails.

1. Into the Wind (In Irons)

Being into the wind or in irons means your sailboat is going straight into the wind (plus or minus 45 degrees from 0), which will prevent your sailboat from… sailing!

Being into the wind can’t be 100% avoided, and it shouldn’t be, but it’s generally not where you want to be if you plan on moving.

The into the wind point of sail is more often a pivot point for when performing other sailing actions including tacking as well as raising and lowering the mast.

When tacking, your point of sail will change from one side of the sailboat to another while crossing the into the wind point of sail. If you’re not able to cross this point of sail fast enough and get stuck, this is called being “taken aback”.

This is also considered the “no-go zone” or “no sail zone” because, you guessed it, you won’t be going anywhere fast when in this space for too long.

If your sailboat’s in the into the wind point of sail for a long enough time, your sailboat will lose all forward momentum and end up sitting around.

2. Close Hauled

The close hauled point of sail is a tad bit greater than the 45-degree mark on either side of the sailboat.

When at this point of sail, you’ll sail upwind and is often called “beating” as well as “working windward” since your boat is moving toward the wind. Sailing close hauled means you’ll be feeling the wind much more as a captain and crew member!

While sailing close hauled, your sail will be functioning as similar as it can to a wing on an airplane due to it cutting the wind dead on resulting in generating a lot of life.

As a matter of fact, this is when you’ll have the tightest sail trim. The closer you are to the wind (or the “no-go zone”), the more to “point” your sailboat will be.

3. Close Reach

As your sailboat “bears away” (moves away from the wind), it’ll enter the close reach point of sail. This point of sail sits right in between the close hauled and beam reach points of sail on either the port or starboard side of a sailboat. Close reach is a fun and fast point of sail for many sailors!

Close reach is the closest point of sail to the “no-go zone” as any other point of sail, so it’s important to pay attention to the wind and your boat sails.

Since sail trim is so important when it comes to your sailboats speed, it’s important in a close haul to keep your sail tight (similar to a close hauled point of sail) but loose enough so it’s just on the verge of luffing.

4. Beam Reach

When entering a beam reach point of sail, your sailboat will be perpendicular to the wind either on the starboard or port side.

Being in beam reach means you’ll be letting your sails halfway out and you’ll be moving relatively faster than other points of sail. As a matter of fact, it’s known to be the fastest point of sail when on a sailboat!

Not only is beam reach the fastest point of sail on a sailboat, but it’s also the most comfortable due to having more control.

The way in which the wind hits your sails at this point of sail means your boat will be transferring energy more efficiently from the sideways force of the wind to the propelling motion forward.

5. Broad Reach

Moving away from a beam reach and into a broad reach point of sail results in letting your sails out about 2/3 of the way.

At this point of sail, the wind is not coming astern from your sailboat and your sail will act more like a parachute than a wing. Now that you’re sailboat’s heading downwind, you’ll also feel a little less of a windy feel but still should be chugging right along.

Since a sail will be out almost the entire way when in a broad reach point of sail, it’ll start to feel like you’re going downhill when it comes to the wind.

While your sailboat won’t yet be truly going entirely downwind, you’ll be on the verge of entering it.

While not the fastest point of sail, I’m a personal fan of broad reach since we’re going at a decent speed and it feels much calmer (in terms of the wind speed) than more windward points of sail.

When you let your sails out the most they can go and the wind is coming directly behind your sailboat, you’ll sail downwind and you’re definitely on a running point of sail.

This point of sail can truly feel like you’re running downhill since you have the force of the wind directly propelling you and your sailboat forward. As a matter of fact, it acts a lot like a parachute and really feels great!

Also known as a “dead run”, the running point of sail doesn’t require critical attention to be made on the sail trim.

Depending on the strength of the wind speed, this means you can consider putting up a genoa or spinnaker sail to really get your sailboat moving when sailing directly downwind.

If you feel that the wind is fairly constant in terms of direction and intensity, this is a great time to put those massive colorful sails up!

How a Sail Works

When I first learned how to sail, I thought the sail was always acting kind of like a kite and simply floating across the water. Well, it turns out that it’s a little more complicated and interesting than that!

As I mentioned before, the sail can act in two different ways: as a wing and as a parachute.

When in the close hauled, close reach, and partially the beam reach points of sail your sailboat’s sail is acting a lot like a wing .

Based on the magnitude and angle at which the true wind and sailboat are traveling, the combination of the two will produce an apparent wind force.

The transfer of energy to produce a forward moving force is mainly due to the sail, keel, and hull .

Essentially, the sail catches the wind’s energy forcing the sailboat to tilt to the side followed by resistance to this tilting from the keel allowing the hull to effectively cut through the water with the remaining force.

When in the broad reach and running points of sail, these forces are still at play resulting in a wing-like action, however, in these points of sail the true wind and sailboat forces are much more aligned.

Essentially, this produces more of a parachute effect as opposed to a wing since the apparent wind force is indistinguishable from the other forces.

Related Questions

What is the best point of sail? The best point of sail is based on personal preference, but the fastest and most comfortable point of sail is beam reach. The combination of the lateral force from the wind onto the sail and the resisting force from the keel produces the strongest forward-moving force on a sailboat.

What is the difference between a jib and genoa sail? Both a jib and genoa sail are sails hoisted at the fore of a sailboat with the genoa being larger in size. The genoa sail oftentimes overlaps the mast due to its size and is mainly used when in a running point of sail.

How do you turn a sailboat? Turning a sailboat occurs when performing a tack or jibe (gybe). Tacking happens when a sailboat is turning into the wind, which requires a traversal through the “no-go zone”. Conversely, jibing happens when traversing through the running point of sail.

Get the very best sailing stuff straight to your inbox

Nomadic sailing.

At Nomadic Sailing, we're all about helping the community learn all there is to know about sailing. From learning how to sail to popular and lesser-known destinations to essential sailing gear and more.

Quick Links

Business address.

1200 Fourth Street #1141 Key West, FL 33040 United States

Copyright © 2024 Nomadic Sailing. All rights reserved. Nomadic Sailing is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

How Sails Work: Understanding the Basics

Table of Contents

Last Updated on September 1, 2023 by Boatsetter Team

Sailing is all about physics and geometry but don’t worry, it’s not too hard to learn. Once the theory is down, it’s all a matter of practice. Let’s look at what sails are and how they work.

Book a sailboat rental & set out on your next expedition

Aerodynamics, hydrodynamics & modern sails

Sails work like airplane wings, except they’re vertical rather than horizontal. As the wind hits the front of a curved sail, it splits, passing on both the downwind (leeward) side and upwind (windward) side.

The leeward wind travels farther due to the curvature of the sail and creates a low-pressure area while the windward wind travels a shorter distance and reaches the aft end faster – together, they create aerodynamic lift that “pulls” the boat forward .

The keel or centerboard in the water below the hull prevents the boat from being pushed sideways. With the lift of the sails and the lateral push or hydrodynamics of the keel, the boat is propelled forward. Where the wind concentrates force in the sails is called the center of effort, while the keel below is called the center of lateral resistance.

Most modern sailboats have a forward (or headsail) and a mainsail. The headsail may be called a genoa, jib, or staysail (different sizes) and is attached at the top of the mast and leads down at an angle to the bow . It’s controlled by lines called sheets. The mainsail is supported by the mast and is attached at the bottom to a lateral spar called the boom.

Parts of a sail