Standing Rigging (or ‘Name That Stay’)

Published by rigworks on november 19, 2019.

Question: When your riggers talk about standing rigging, they often use terms I don’t recognize. Can you break it down for me?

From the Rigger: Let’s play ‘Name that Stay’…

Forestay (1 or HS) – The forestay, or headstay, connects the mast to the front (bow) of the boat and keeps your mast from falling aft.

- Your forestay can be full length (masthead to deck) or fractional (1/8 to 1/4 from the top of the mast to the deck).

- Inner forestays, including staysail stays, solent stays and baby stays, connect to the mast below the main forestay and to the deck aft of the main forestay. Inner forestays allow you to hoist small inner headsails and/or provide additional stability to your rig.

Backstay (2 or BS) – The backstay runs from the mast to the back of the boat (transom) and is often adjustable to control forestay tension and the shape of the sails.

- A backstay can be either continuous (direct from mast to transom) or it may split in the lower section (7) with “legs” that ‘V’ out to the edges of the transom.

- Backstays often have hydraulic or manual tensioners built into them to increase forestay tension and bend the mast, which flattens your mainsail.

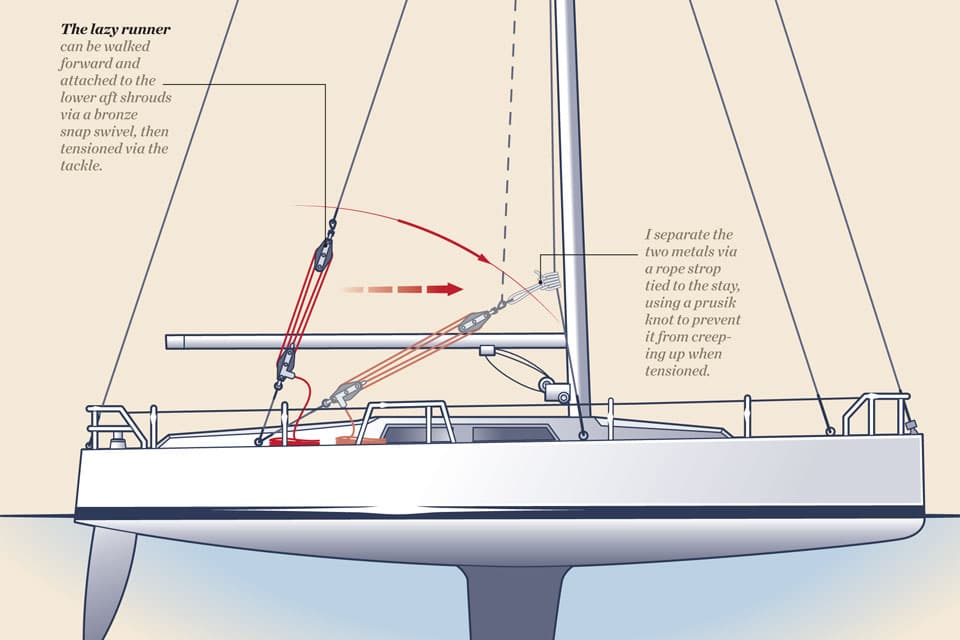

- Running backstays can be removable, adjustable, and provide additional support and tuning usually on fractional rigs. They run to the outer edges of the transom and are adjusted with each tack. The windward running back is in tension and the leeward is eased so as not to interfere with the boom and sails.

- Checkstays, useful on fractional rigs with bendy masts, are attached well below the backstay and provide aft tension to the mid panels of the mast to reduce mast bend and provide stabilization to reduce the mast from pumping.

Shrouds – Shrouds support the mast from side to side. Shrouds are either continuous or discontinuous .

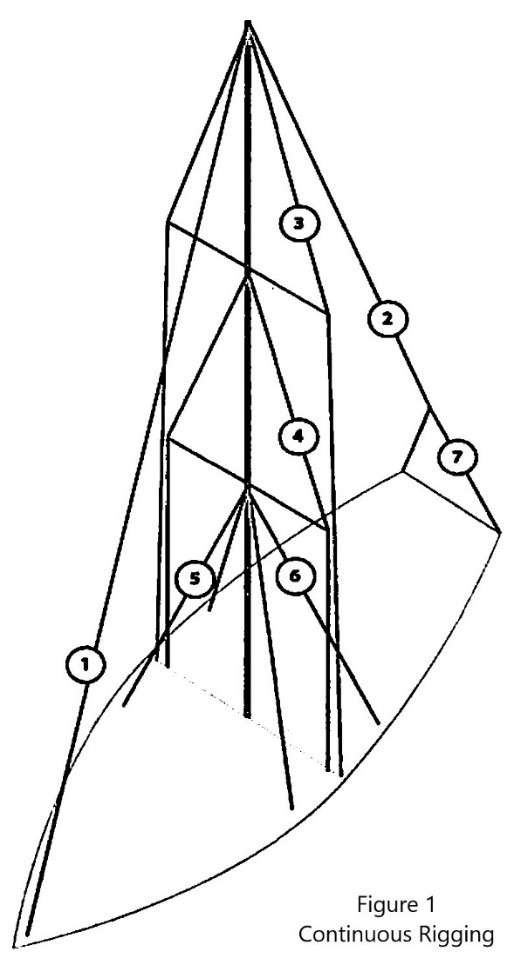

Continuous rigging, common in production sailboats, means that each shroud (except the lowers) is a continuous piece of material that connects to the mast at some point, passes through the spreaders without terminating, and continues to the deck. There may be a number of continuous shrouds on your boat ( see Figure 1 ).

- Cap shrouds (3) , sometimes called uppers, extend from masthead to the chainplates at the deck.

- Intermediate shrouds (4) extend from mid-mast panel to deck.

- Lower shrouds extend from below the spreader-base to the chainplates. Fore- (5) and Aft-Lowers (6) connect to the deck either forward or aft of the cap shroud.

Discontinuous rigging, common on high performance sailboats, is a series of shorter lengths that terminate in tip cups at each spreader. The diameter of the wire/rod can be reduced in the upper sections where loads are lighter, reducing overall weight. These independent sections are referred to as V# and D# ( see Figure 2 ). For example, V1 is the lowest vertical shroud that extends from the deck to the outer tip of the first spreader. D1 is the lowest diagonal shroud that extends from the deck to the mast at the base of the first spreader. The highest section that extends from the upper spreader to the mast head may be labeled either V# or D#.

A sailboat’s standing rigging is generally built from wire rope, rod, or occasionally a super-strong synthetic fibered rope such as Dyneema ® , carbon fiber, kevlar or PBO.

- 1×19 316 grade stainless steel Wire Rope (1 group of 19 wires, very stiff with low stretch) is standard on most sailboats. Wire rope is sized/priced by its diameter which varies from boat to boat, 3/16” through 1/2″ being the most common range.

- 1×19 Compact Strand or Dyform wire, a more expensive alternative, is used to increase strength, reduce stretch, and minimize diameter on high performance boats such as catamarans. It is also the best alternative when replacing rod with wire.

- Rod rigging offers lower stretch, longer life expectancy, and higher breaking strength than wire. Unlike wire rope, rod is defined by its breaking strength, usually ranging from -10 to -40 (approx. 10k to 40k breaking strength), rather than diameter. So, for example, we refer to 7/16” wire (diameter) vs. -10 Rod (breaking strength).

- Composite Rigging is a popular option for racing boats. It offers comparable breaking strengths to wire and rod with a significant reduction in weight and often lower stretch.

Are your eyes crossing yet? This is probably enough for now, but stay tuned for our next ‘Ask the Rigger’. We will continue this discussion with some of the fittings/connections/hardware associated with your standing rigging.

Related Posts

Ask the Rigger

Do your masthead sheaves need replacing.

Question: My halyard is binding. What’s up? From the Rigger: Most boat owners do not climb their masts regularly, but our riggers spend a lot of time up there. And they often find badly damaged Read more…

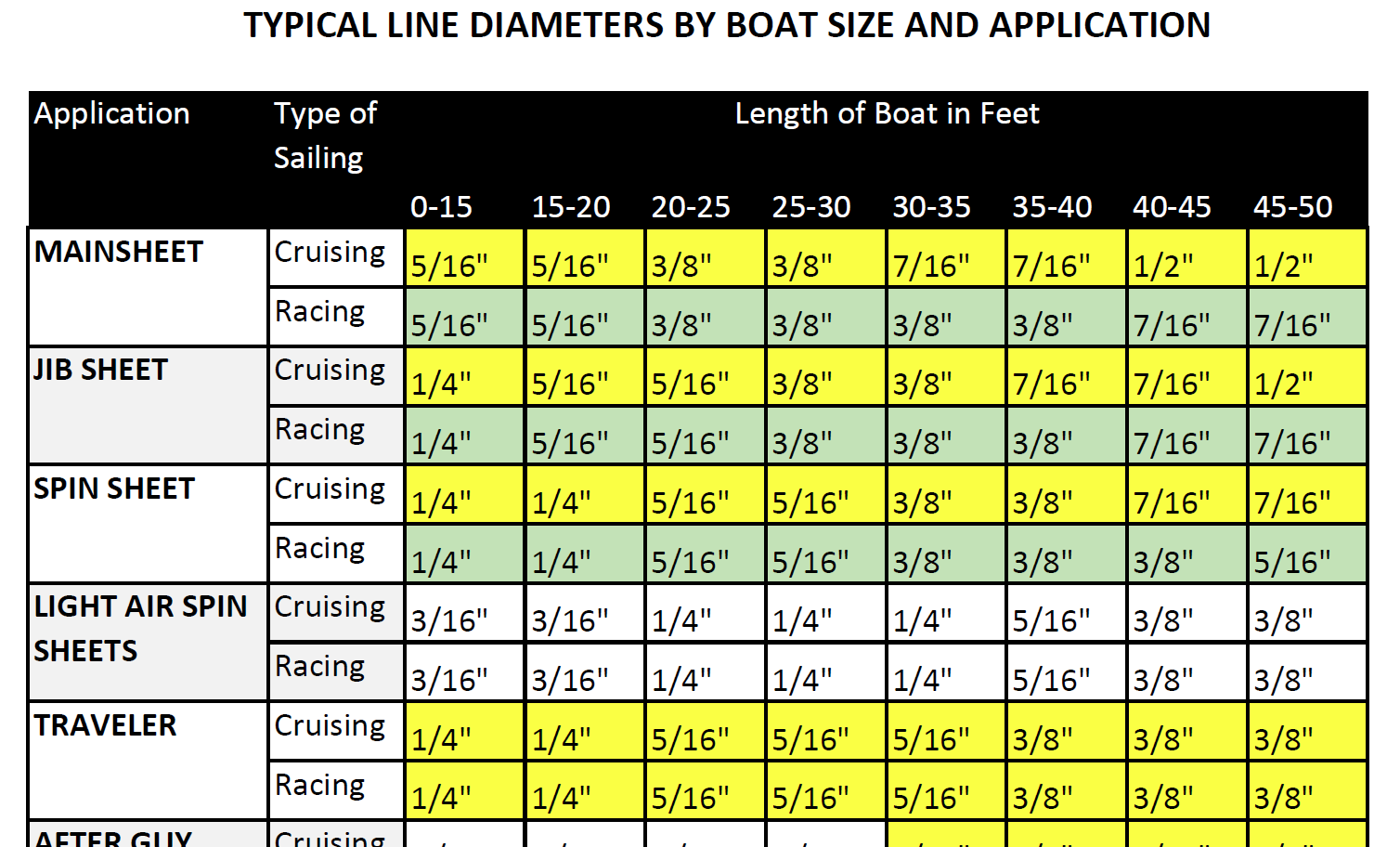

Selecting Rope – Length, Diameter, Type

Question: Do you have guidelines for selecting halyards, sheets, etc. for my sailboat? From the Rigger: First, if your old rope served its purpose but needs replacing, we recommend duplicating it as closely as possible Read more…

Spinlock Deckvest Maintenance

Question: What can I do to ensure that my Spinlock Deckvest is well-maintained and ready for the upcoming season? From the Rigger: We are so glad you asked! Deckvests need to be maintained so that Read more…

What is a Sailboat Stay?

Last Updated by

Daniel Wade

June 15, 2022

A sailboat stay is a cable or line that supports the mast. Stays bear a significant portion of the mast load.

Stays are a significant part of a sailboat's standing rigging, and they're essential for safe sailing. Stays support the mast and bear the stress of the wind and the sails. Losing a stay is a serious problem at sea, which is why it's essential to keep your stays in good condition.

Table of contents

How to Identify Sailboat Stays

Sailboat stays connected to the top of the mast to the deck of the sailboat. Stays stabilize the mast in the forward and aft directions. Stays are typically mounted to the very front of the bow and the rearmost part of the stern.

Sailboat Forestay

The forestay connects the top of the mast to the bow of the boat. The forestay also serves an additional purpose—the jib sail luff mounts to the forestay. In fact, the jib is hoisted up and down the forestay as if it were a mast.

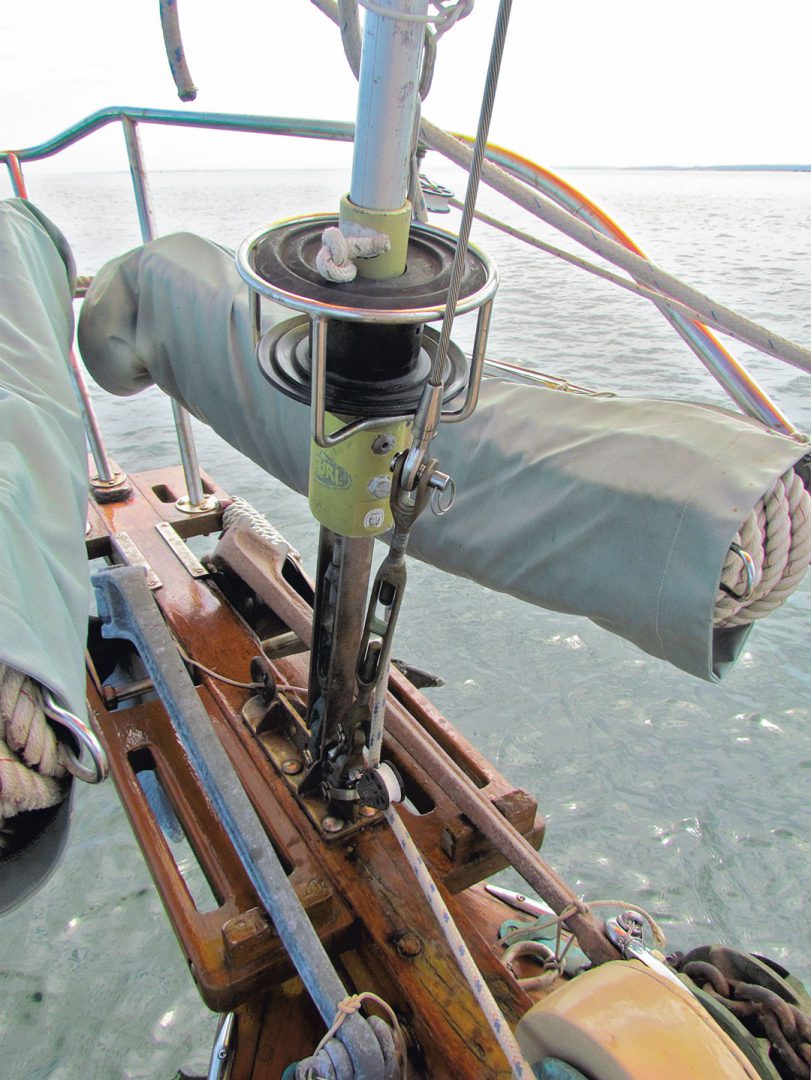

Boats equipped with roller furlings utilize spindles at the top and base of the forestay. The spindles rotate to furl and unfurl the jib. Roller furlings maintain the structural integrity of a standard forestay.

Sailboat Backstay

Backstays aren't as multifunctional as forestays. The backstay runs from the top of the mast (opposite the forestay) to the stern of the sailing vessel, and it balances the force exerted by the forestay. Together, the forestay and the backstay keep the mast upright under load.

Sailboat Stay vs. Shroud

Stays and shrouds are often confused, as they essentially do the same thing (just in different places). Stays are only located on the bow and stern of the vessel—that's fore and aft. Shrouds run from the port and starboard side of the hull or deck to the top of the mast.

Best Sailboat Stay Materials

Traditional sailboat stays were made of rope and organic line. These materials worked fine for thousands of years, and they still do today. However, rope has limitations that modern sailboat stays don't.

For one, traditional rope is organic and prone to decay. It also stretches, which can throw off the balance of the mast and cause serious problems. Other materials, such as stainless steel, are more ideal for the modern world.

Most modern fiberglass sailboats use stainless steel stays. Stainless stays are made of strong woven stainless steel cable, which resists corrosion and stress. Stainless cables are also easy to adjust.

Why are Stays Important?

Stays keep the mast from collapsing. Typical sailboats have lightweight hollow aluminum masts. Alone, these thin towering poles could never hope to withstand the stress of a fully-deployed sail plan. More often than not, unstayed masts of any material fail rapidly under sail.

When properly adjusted, stays transfer the force of the wind from the thin and fragile mast to the deck or the hull. They distribute the power of the wind over a wider area and onto materials that can handle it. The mast alone simply provides a tall place to attach the head of the sail, along with a bit of structural support.

Sailboat Chain Plates

Sailboat stays need a strong mounting point to handle the immense forces they endure. Stays mount to the deck on chainplates, which further distribute force to support the load.

Chainplates are heavy steel mounting brackets that typically come with two pieces. One plate mounts on top of the deck and connects to the stay. The other plate mounts on the underside of the deck directly beneath the top plate, and the two-bolt together.

Mast Stay Mounting

Stays mount to the mast in several ways depending on the vessel and the mast material. On aluminum masts, stays often mount to a type of chain plate called a "tang." A tang consists of a bracket and a hole for a connecting link. Aluminum masts also use simple U-bolts for mounting stays.

Wooden masts don't hold up to traditional brackets as well as aluminum. A simple u-bolt or flat bolt-on bracket might tear right out. As a result, wooden masts often use special collars with mounting rings on each side. These collars are typically made of brass or stainless steel.

Sailboat Stays on Common Rigs

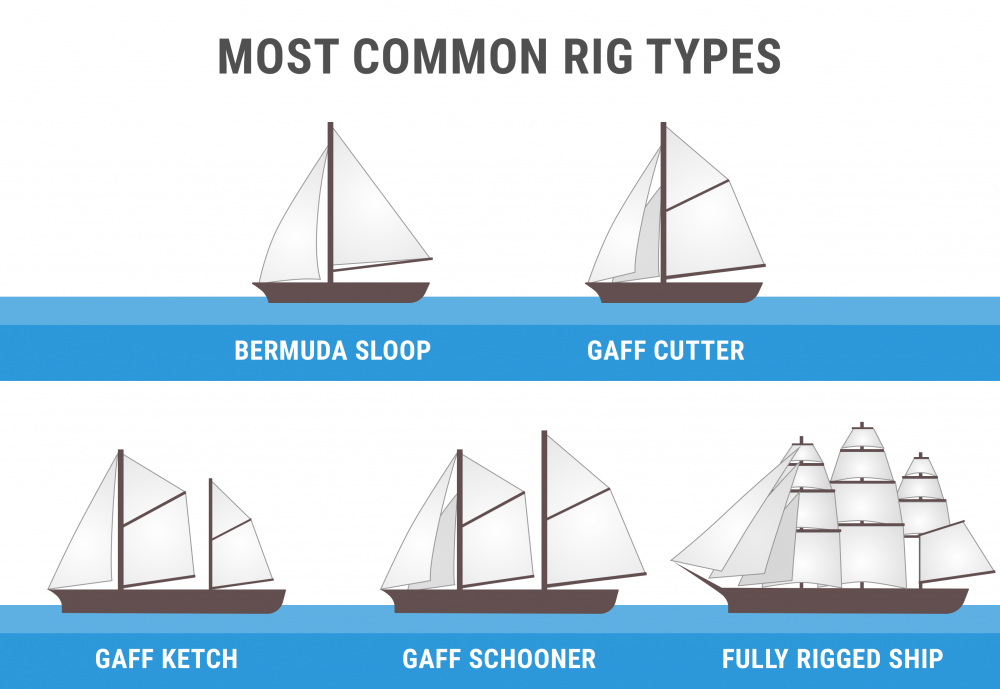

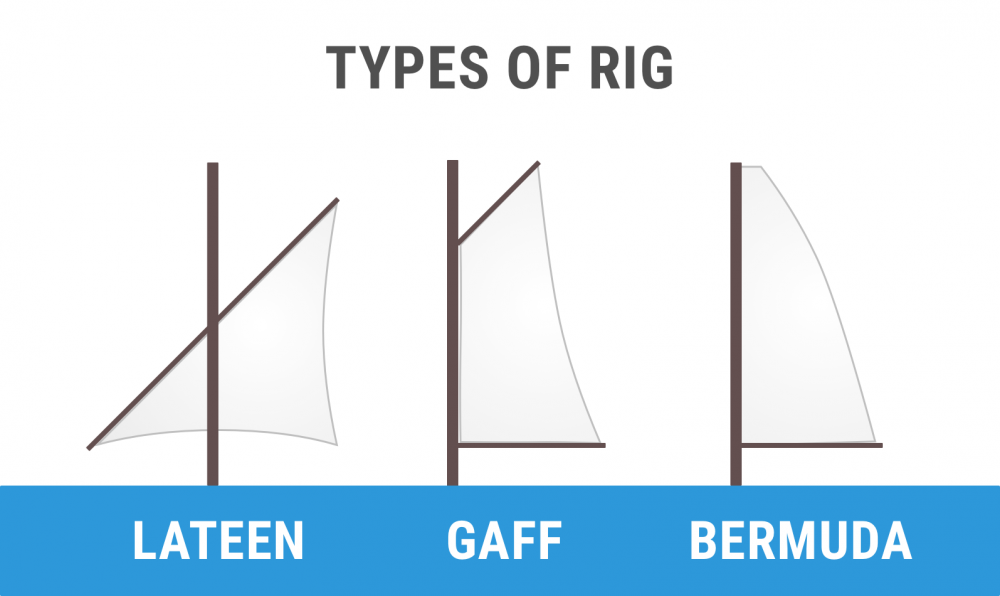

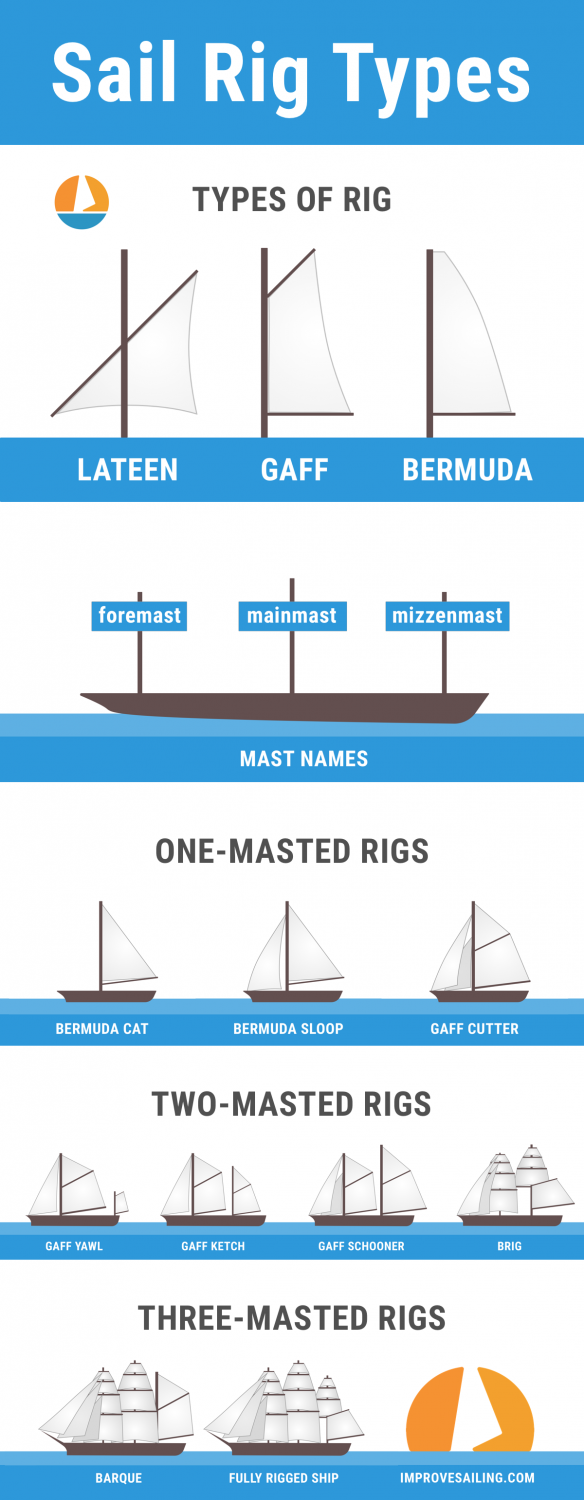

Stays on a Bermuda-rigged sailboat are critical. Bermuda rigs use a triangular mainsail . Triangular sails spread their sail area vertically, which necessitates a tall mast.

Bermuda rig masts are often thin, hollow, and made of lightweight material like aluminum to avoid making the boat top-heavy. As a result, stays, and shrouds are of critical importance on a Bermuda rig.

Traditional gaff-rigged sail plans don't suffer as much from this issue. Gaff rigs use a four-pointed mainsail. This sail has a peak that's taller than the head and sometimes taller than the mast.

Gaff-rigged cutters, sloops, schooners, and other vessels use comparatively shorter and heavier masts, which are less likely to collapse under stress. These vessels still need stays and shrouds, but their stronger masts tend to be more forgiving in unlucky situations.

How to Adjust Sailboat Stays

Sailboat stays and shrouds must be checked and adjusted from time to time, as even the strongest stainless steel cable stretches out of spec. Sailboats must be in the water when adjusting stays. Here's the best way to keep the proper tension on your stays.

Loosen the Stays

Start by loosening the forestay and backstay. Try to do this evenly, as it'll reduce the stress on the mast. Locate the turnbuckles and loosen them carefully.

Match the Turnbuckle Threads

Before tightening the turnbuckle again, make sure the top and bottom threads protrude the same amount. This reduces the chance of failure and allows you to equally adjust the stay in both directions.

Center the Mast

Make sure the mast is centered on its own. If it's not, carefully take up the slack in the direction you want it to go. Once the mast is lined up properly, it's time to tighten both turnbuckles again.

Tighten the Turnbuckles

Tighten the turnbuckles as evenly as possible. Periodically monitor the direction of the mast and make sure you aren't pulling it too far in a single direction.

Determine the Proper Stay Pressure

This step is particularly important, as stays must be tightened within a specific pressure range to work properly. The tension on a sailboat stay ranges from a few hundred pounds to several tons, so it's essential to determine the correct number ahead of time. Use an adjuster to monitor the tension.

What to Do if you Lose a Stay

Thankfully, catastrophic stay and shroud failures are relatively rare at sea. Losing a mast stay is among the worst things that can happen on a sailboat, especially when far from shore.

The stay itself can snap with tremendous force and cause injury or damage. If it doesn't hurt anyone, it'll certainly put the mast at risk of collapsing. In fact, if you lose a stay, your mast will probably collapse if stressed.

However, many sailors who lost a forestay or backstay managed to keep their mast in one piece using a halyard. In the absence of a replacement stay, any strong rope can offer some level of protection against dismasting .

How to Prevent a Stay Failure

Maintenance and prevention is the best way to avoid a catastrophic stay failure. Generally speaking, the complete failure of a stay usually happens in hazardous weather conditions or when there's something seriously wrong with the boat.

Stays sometimes fail because of manufacturing defects, but it's often due to improper tension, stripped threads, or aging cable that hasn't been replaced. Regular maintenance can prevent most of these issues.

Check the chainplates regularly, as they can corrode quietly with little warning. The deck below the chainplates should also be inspected for signs of rot or water leakage.

When to Replace Standing Rigging

Replace your stays and shrouds at least once every ten years, and don't hesitate to do it sooner if you see any signs of corrosion or fraying. Having reliable standing rigging is always worth the added expense.

Choosing a high-quality stay cable is essential, as installing substandard stays is akin to playing with fire. Your boat will thank you for it, and it'll be easier to tune your stays for maximum performance.

Related Articles

I've personally had thousands of questions about sailing and sailboats over the years. As I learn and experience sailing, and the community, I share the answers that work and make sense to me, here on Life of Sailing.

by this author

Sailboat Parts

Learn About Sailboats

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

Affordable Sailboats You Can Build at Home

September 13, 2023

Best Small Sailboat Ornaments

September 12, 2023

Discover the Magic of Hydrofoil Sailboats

December 11, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

Sailboat Stays and Shrouds: Essential Rigging Components Explained

by Emma Sullivan | Aug 21, 2023 | Sailboat Maintenance

Short answer: Sailboat stays and shrouds

Sailboat stays and shrouds are essential components of the rigging system that provide support and stability to the mast. Stays run from the masthead to various points on the boat, preventing forward and backward movement, while shrouds connect the mast laterally to maintain side-to-side stability. Together, they help distribute the forces acting on the mast and ensure safe sailing .

Understanding Sailboat Stays and Shrouds: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction: Sailing is an exhilarating experience, but it requires a deep understanding of the various components that make up a sailboat . One crucial aspect that every sailor should grasp is the concept of stays and shrouds. These vital elements not only provide support and stability to the mast but also play a significant role in determining the overall performance of the sailboat. In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything you need to know about sailboat stays and shrouds.

What are Stays and Shrouds? Stays and shrouds are essential rigging components that hold the mast in place and control its movements during sailing. They primarily serve two distinct purposes – providing support for the mast against excessive sideways forces (known as lateral or side-to-side loads) while allowing controlled flexing, and keeping the mast aligned with respect to both pitch (fore-aft) and roll (side-to-side) axes.

The Difference between Stays and Shrouds: Although often used interchangeably, stays and shrouds have specific functions on a sailboat rigging system. Stays usually refer to those wires or cables that run forward from the head of the mast, attaching it to various points on the bow or foredeck. They help resist fore-and-aft loads placed upon the mast, such as when sailing upwind, preventing it from bending too much under pressure.

On the other hand, shrouds typically refer to rigging lines connecting laterally from both sides of the masthead down towards deck level or chainplates located on either side of the boat’s cabin top or hull. Unlike stays, they primarily counteract side-to-side forces acting on the mast due to wind pressure exerted against sails during different points of sail.

Types of Stays: A typical sailboat may consist of different types of stays based on their location on the mast. Some of the common types include:

1. Forestay: The forestay is a prominent stay that runs from the top of the mast to the bow or stemhead fitting at the boat’s front . It is responsible for supporting most of the fore-and-aft loads acting upon a sailboat rigging system, keeping the mast in position while under tension from sails .

2. Backstay: The backstay runs from the top of the mast to either stern or transom fittings at the aft end of a sailboat. It acts as an opposing force to counteract forward bending moments occurring on larger boats when sailing into a headwind or during heavy gusts.

3. Inner Stays: Found on some rigs with multiple masts or taller sailboats, inner stays run parallel to and inside other stays (such as forestay and backstay). These provide additional support and rigidity when deploying smaller headsails closer to centerline during specific wind conditions.

Types of Shrouds: Similar to stays, shrouds can vary based on their positioning on each side of the masthead and hull structure. Some commonly used shroud types are:

1. Upper Shrouds: These are positioned higher up on a sailboat mast , connecting near its upper section down towards deck level or chainplates for lateral stability against the force exerted by sailing sails.

2. Lower Shrouds: Positioned lower down on a sailboat’s mast , these connect near its midpoint and extend towards lower deck sections or chainplates. They serve mainly as reinforcing elements against lateral forces experienced while sailing in strong winds .

3. Jumpers/Checkstays: Jumpers (or checkstays) are typically temporary shroud additions used when depowering or controlling mast bend in certain wind conditions or point of sail, especially during racing events where fine-tuning sail shape is critical.

Conclusion: Sailboat stays and shrouds are essential components that provide critical support, stability, and control to the mast. Understanding their purpose and types is crucial for every sailor looking to optimize their vessel’s performance while ensuring safe sailing. By comprehensively knowing the role of stays and shrouds, you can confidently navigate the waters while harnessing the power of wind in pursuit of your sailing adventures.

Step-by-Step Instructions for Proper Installation of Sailboat Stays and Shrouds

Installing sailboat stays and shrouds may seem like a daunting task, but with the right knowledge and proper instructions, it can be accomplished smoothly. Stays and shrouds are crucial components of a sailboat’s rigging system that provide support and stability to the mast. In this step-by-step guide, we will walk you through the process of installing these vital elements for safe and efficient sailing.

Step 1: Prepare your Equipment

Before beginning any installation, ensure that you have all the necessary tools and materials at hand. This includes stay wires, turnbuckles, cotter pins, wire cutters, measuring tape, swage fittings (if applicable), wrenches appropriate for your boat’s hardware sizes, and a well-organized workspace. Having everything prepared ahead of time allows for smoother progress throughout the installation procedure.

Step 2: Measure & Cut Stay Wires

Accurate measurements are crucial when it comes to stays and shrouds installation. Using a measuring tape, determine the required length for each stay wire by taking precise measurements from their designated attachment points on deck to the masthead or other relevant attachment points. It is important to leave room for tension adjustment using turnbuckles later on.

After obtaining accurate measurements, use wire cutters to trim each stay wire accordingly. Be sure to trim them slightly longer than measured lengths initially indicated because precision can only be achieved once all connections are made.

Step 3: Attach Wires to Mast Fittings

Now that you have your measured and cut stay wires ready, it’s time to attach them securely to the appropriate mast fittings . Depending on your boat’s design and specific rigging details, this step can vary slightly. Look for pre-existing attachment points designed specifically for stays or fittings specifically configured for thread-on stays if applicable.

Ensure each connection is secure by threading or whatever means necessary as per your boat’s requirements . Double-check that there is no unwanted slack while leaving space for later tension adjustments.

Step 4: Deck Attachment Points

Move on to attaching the stay wires to their designated deck attachment points. These points are usually found near the bow area, and there may be specific fittings designed just for this purpose. Follow your operational manual or consult experienced sailors if you are unsure about the correct attachment points.

Again, double-check that all connections are securely fastened, without any excess slack. It is always better to have a slight bit of extra wire length here than have inadequate length at this stage.

Step 5: Install Turnbuckles

With the stays securely connected at both ends, it’s time to insert turnbuckles. Turnbuckles are essential tools for adjusting the tension in stay wires. Attach these devices to each stay wire by screwing them into the corresponding threaded fitting on either end of the stays. Ensure they are tightened securely but not over-tightened at this stage; you still need room for adjustments and tuning.

Step 6: Secure with Cotter Pins or Locking Nuts

To prevent accidental loosening of turnbuckles due to vibrations or rough sail conditions, make sure to secure them using cotter pins or locking nuts provided by your boat’s manufacturer. Place a cotter pin through the hole located in one side of the turnbuckle and bend it back upon itself, ensuring that it does not interfere with adjacent rigging components or sails.

Alternatively, locking nuts can be used by tightening them against each side of the turnbuckle threads once adjusted correctly –This provides an additional layer of security against unexpected loosening during sailing adventures !

Step 7: Inspect & Adjust Tension

Before hitting the water and setting sail , take a moment to inspect all connections thoroughly. Verify that each wire is properly aligned and does not show signs of damage like frays or kinks—Pay attention to potential chafe points where movement can wear against another object or surface.

To adjust tension, gradually tighten or loosen the turnbuckles as necessary. Be cautious and make small adjustments while periodically checking for an evenly balanced mast, ensuring that it remains straight and true.

By following these step-by-step instructions meticulously, you can ensure a proper installation of sailboat stays and shrouds. Remember to take your time, double-check all connections, and consult with professionals or experienced sailors if any doubts arise. With a meticulous approach and attention to detail, your sailboat rigging will be safe, stable, and ready for smooth sailing adventures!

Frequently Asked Questions about Sailboat Stays and Shrouds: Everything You Need to Know

Have you ever found yourself marveling at the majesty of a sailboat, wondering how it is able to harness the power of the wind and navigate through vast oceans? If you are a sailing enthusiast or considering embarking on a sailing adventure, understanding the intricacies of sailboat stays and shrouds is paramount. In this comprehensive blog post, we will address frequently asked questions about sailboat stays and shrouds, equipping you with everything you need to know.

1. What are Sailboat Stays and Shrouds?

Sailboat stays and shrouds are vital components of a boat’s standing rigging system that help support the mast while ensuring stability during sailing. Simply put, they prevent the mast from toppling over under excessive pressure from the sails or adverse weather conditions. While these terms may sound interchangeable to novices, there are important distinctions between them.

Stays: Stays are tensioned cables or wires attached to various points on the mast and radiate outwards in multiple directions supporting it against fore-and-aft movement. The most common types include forestays (located at the bow), backstays (attached to the stern), side stays (running sideways along both port and starboard sides), and inner forestays.

Shrouds: On the other hand, shrouds provide lateral support to counteract sideways forces acting on the mast. They run diagonally from their connection points on deck-level chainplates outwards towards optimized positions along the spreaders near midway up the mast.

2. What materials are used for Sailboat Stays and Shrouds?

Traditionally, steel wire was predominantly used for both stays and shrouds due to its strength and durability. However, modern advancements have introduced alternative materials such as synthetic fibers like Dyneema or carbon fiber composites. These lightweight alternatives possess remarkable tensile strength while offering corrosion resistance advantages over traditional wire options.

3. How tight should Sailboat Stays and Shrouds be?

Maintaining the appropriate tension in your sailboat’s stays and shrouds is crucial for maintaining integrity and overall sailing performance. Correct tension ensures that the mast remains properly aligned while allowing it to flex as required, absorbing dynamic forces from wind gusts.

To determine optimal tension, consult your sailboat’s manufacturer guidelines or consult with a professional rigging specialist. Adjustments may also vary depending on sea state or anticipated weather conditions . Proper tuning necessitates periodic evaluation to ensure the stays and shrouds’ tension remains within specifications.

4. How do Sailboat Stays and Shrouds affect sailing performance ?

The correct alignment, tautness, and positioning of sailboat stays and shrouds significantly impact sailing performance due to their influence on mast bend characteristics. Adjusting stay tension can control how much a mast bends under load: tightened stays flatten the mainsail’s profile for increased pointing ability in light winds, while looser tensions promote fuller profiles for enhanced power in heavier winds .

Shroud positions also dictate sideways motion of the mast; fine-tuning their tension governs how efficiently a boat can maintain a desired course when encountering various wind strengths and angles.

5. What are some common signs of wear or damage in Sailboat Stays and Shrouds?

As essential as they are, sailboat stays and shrouds are subjected to immense loads that can lead to wear over time. Routine inspection is vital to identify any potential issues before they escalate into major rigging failures.

Signs of wear or damage may include rust or corrosion on metal components, cracked insulation around terminals, broken strands on wire rigging, visible rigging deformation or elongation under load, unusual vibrations onboard while sailing, or creaking noises originating from the mast during maneuvers.

In such instances, swift action should be taken by replacing affected parts immediately or seeking assistance from experienced rigging professionals.

By familiarizing yourself with the essentials of sailboat stays and shrouds, you empower yourself to enjoy a safer and more rewarding sailing experience. Remember to conduct regular inspections, adhere to manufacturer recommendations, and consult professionals when necessary. Now, set sail with confidence as you venture into the salty unknown!

Exploring the Importance of Sailboat Stays and Shrouds in Ensuring Safety at Sea

When it comes to sailing, safety should always be the number one priority. The open waters of the sea can be unpredictable and unforgiving, making it crucial for sailors to have a thorough understanding of their sailboat ‘s rigging system. One vital component of this system is sailboat stays and shrouds, which play a significant role in ensuring safety onboard.

Sailboat stays and shrouds are specialized cables or wires that support the mast, providing stability and preventing it from collapsing under the pressure of wind forces. These essential rigging elements act as a lifeline for the entire vessel, keeping everything intact during even the toughest conditions at sea.

The primary purpose of stays and shrouds is to distribute the load evenly throughout the mast structure. By doing so, they prevent excessive stress on specific areas and reduce the risk of structural failure. This balance is especially critical when sailboats encounter strong winds or rough seas that can exert immense pressure on the mast.

Imagine cruising along peacefully when suddenly you encounter strong gusts of wind. Without properly tensioned stays and shrouds, your mast could bend or break under these intense forces, compromising your safety and potentially causing severe damage to your vessel. Well-maintained stays and shrouds ensure that your mast remains stable even in adverse weather conditions by withstanding these forces without deformation.

However, ensuring that your sailboat’s rigging is reliable isn’t just about maintaining functionality—it demands meticulous attention to detail as well. Stays and shrouds need periodic inspection to identify any signs of wear or corrosion that may weaken their integrity over time. A frayed cable or rusty hardware might not seem like much at first glance, but they could lead to catastrophic failures when put under stress.

Safety at sea also requires understanding how different types of stays and shrouds work together to optimize performance in varying sailing conditions. While staying safe is crucial, performance matters too! Different sailboat designs accommodate different rigging configurations, and knowledgeable sailors carefully select the right combinations to enhance their vessel’s maneuverability. The strategic placement of stays and shrouds aids in controlling the shape and orientation of sails, enabling efficient sailing even in challenging weather.

In this era of advanced technologies, some sailors may wonder if traditional stays and shrouds are still essential with other innovations available. However, it’s crucial to remember that age-old methods often endure for a reason: their reliability. Modern alternatives might offer convenience or weight-saving benefits, but they seldom match the robustness and simplicity of time-tested techniques.

The exploration of the importance of sailboat stays and shrouds ultimately emphasizes the significance of investing time and resources into proper knowledge, maintenance, and selection. As a sailor, prioritizing safety by ensuring the integrity of these critical components can mean all the difference between a pleasurable voyage adrift on calm seas versus surviving treacherous storms.

So, before embarking on any maritime adventure, take a moment to appreciate the unsung heroes that uphold your mast—the sailboat stays and shrouds—and make sure they are ready to bear any challenges that await you on your journey to ensure both safe passage and endless memories at sea.

How Sailboat Stays and Shrouds Impact Performance: Tips for Maximizing Efficiency

Sailboats are fascinating vessels that harness the power of the wind to propel through the water. While many factors contribute to a sailboat’s performance, one often overlooked aspect is the impact that stays and shrouds have on its efficiency. In this blog post, we will dive into the intricacies of sailboat stays and shrouds, exploring how they affect performance and providing valuable tips for maximizing efficiency.

To understand the significance of stays and shrouds, let’s first clarify their definitions. Stays are essentially wires or ropes that provide support to keep a mast in place, preventing excessive bending or swaying. Shrouds, on the other hand, refer specifically to those stays that extend from either side of the boat to stabilize the mast laterally.

While seemingly simple components, stays and shrouds play a crucial role in determining a sailboat’s overall performance. Here’s how:

1. Structural stability: Sailboat stays act as primary supports for the mast, ensuring it remains upright against powerful winds . Without adequately tensioned stays and shrouds, masts can buckle or sway excessively under load, compromising sailing performance and even risking structural damage.

2. Sail shape control: Proper tensioning of stays and shrouds directly influences the shape of your sails while underway. By adjusting their tension appropriately, you can manipulate how your sails fill with wind , optimizing their aerodynamic profile for maximum efficiency. Expert sailors effectively use this control mechanism to fine-tune their boat ‘s speed and responsiveness.

3. Windward performance: Efficiently rigged sailboat stays help maintain proper alignment between mast and sails when sailing upwind (also known as pointing). Tensioned shrouds ensure that minimal lateral movement occurs during tacking or jibing maneuvers when changing direction against the wind. This prevention of excess mast movement translates into less energy lost due to unnecessary drag – ultimately improving windward efficiency .

Now that we’ve established the importance of sailboat stays and shrouds let’s delve into some tips for optimizing their performance:

1. Regular inspections: Routine visual inspections are essential to identify any signs of wear, corrosion, or fatigue on your stays and shrouds. Replace frayed ropes or wires promptly, ensuring that all components remain robust and reliable.

2. Correct tensioning: Achieving the optimal tension in your stays and shrouds is vital. Too loose, and you risk mast instability; too tight, and excessive stress loads are placed on the rigging components. Aim for a tension that allows slight flexibility while maintaining structural integrity – seeking advice from an experienced rigger can help find the sweet spot.

3. Invest in quality materials: The quality of your rigging directly impacts its longevity and performance . Opt for high-quality stainless steel wires, synthetic fibers like Dyneema, or carbon fiber alternatives when replacing old rigging components, as these materials offer superior strength-to-weight ratios.

4. Tuning adjustments: To maximize sail shape control, experiment with adjusting the tension of your stays and shrouds during different weather conditions or sailing angles. Fine-tuning these tensions can lead to significant improvements in both speed and responsiveness while ensuring optimum aerodynamic performance at all times.

5. Seek professional advice: Don’t hesitate to reach out to experts in yacht rigging or naval architects for specialist input regarding optimizing your sailboat’s rigging setup. Their expertise can guide you towards refined techniques tailored to suit specific vessel designs or sailing goals.

In conclusion, understanding how sailboat stays and shrouds impact performance is crucial for any sailor aiming to maximize efficiency on the water. By recognizing their significance as key structural supports influencing sail shape control and windward performance, you can optimize your vessel’s potential while enjoying more thrilling voyages than ever before! So make sure to prioritize regular inspections, correct tensioning methods, high-quality materials, tuning adjustments, and professional guidance to unlock the true potential of your sailboat.

Essential Maintenance Tips for Maintaining the Integrity of Sailboat Stays and Shrouds

Sailboat owners and enthusiasts know the importance of regular maintenance to keep their vessels in top condition. Among the vital components that require particular attention are the stays and shrouds – key structural elements that ensure the integrity of a sailboat’s mast and rigging system.

Stays and shrouds are essentially wires or cables that provide crucial support to the mast, allowing it to properly withstand wind pressures and maintain stability during sailing. As they play such a pivotal role in your sailboat’s performance and safety, it is essential to implement regular maintenance practices to ensure their longevity and functionality.

To help you maintain the integrity of your sailboat’s stays and shrouds, we have compiled some essential tips that will not only enhance their lifespan but also contribute to your overall sailing experience:

1. Visual Inspection: Regularly conduct visual inspections of all stays and shrouds with an eagle eye for any signs of wear or damage. Look for frayed or broken strands, corrosion, stretched areas, or loose fittings. It is better to address minor issues early on rather than waiting for them to become major problems.

2. Tension Monitoring: Check the tension of your stays regularly using a suitable tension gauge or by following manufacturer guidelines. Proper tension ensures optimal performance while avoiding excessive strain on both mast and rigging components.

3. Corrosion Control: Saltwater exposure can accelerate corrosion on metal components like turnbuckles, shackles, or terminals. Routinely clean these parts using freshwater after each outing while inspecting them for signs of rust. Applying protective coatings like anti-corrosion sprays can also significantly extend their lifespan.

4. Lubrication: Maintaining a smooth operation within turnbuckles is crucial for proper tension adjustment as well as preventing corrosion seizing between threaded components (e.g., adjusters). Apply marine-grade lubricants periodically, ensuring even distribution across all moving parts.

5. Regular Rig Tuning: Appreciate the importance of proper rig tuning to optimize sail shape and overall stability. Work with a professional rigger to adjust the tension on your sails and shrouds, correcting any sag or excessive flex.

6. Replacing Components: If you notice any signs of wear that cannot be resolved through cleaning, lubrication, or tension adjustment, consider replacing the affected components immediately with high-quality replacements. Neglecting worn stays or shrouds can compromise your sailboat ‘s safety and performance.

7. Professional Rig Inspection: Schedule a professional rig inspection at least once every two years, especially if you engage in more frequent or rigorous sailing activities. Rigging experts have the experience and knowledge to detect potential weaknesses that may not be readily evident to an untrained eye, helping you avoid costly breakdowns during crucial moments.

Remember, maintaining the integrity of sailboat stays and shrouds should be an ongoing priority for all passionate sailors. By following these essential maintenance tips and providing regular care to these vital elements, you can ensure your vessel is ready to conquer waves with reliability and grace. So set sail with confidence knowing that your rigging system is in optimal condition!

Recent Posts

- Sailboat Gear and Equipment

- Sailboat Lifestyle

- Sailboat Maintenance

- Sailboat Racing

- Sailboat Tips and Tricks

- Sailboat Types

- Sailing Adventures

- Sailing Destinations

- Sailing Safety

- Sailing Techniques

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

Ericson 41 Used Boat Review

Mason 33 Used Boat Review

Beneteau 311, Catalina 310 and Hunter 326 Used Boat Comparison

Maine Cat 41 Used Boat Review

Tips From A First “Sail” on the ICW

Tillerpilot Tips and Safety Cautions

Best Crimpers and Strippers for Fixing Marine Electrical Connectors

Thinking Through a Solar Power Installation

Getting the Most Out of Older Sails

How (Not) to Tie Your Boat to a Dock

Stopping Mainsheet Twist

Working with High-Tech Ropes

Fuel Lift Pump: Easy DIY Diesel Fuel System Diagnostic and Repair

Ensuring Safe Shorepower

Sinking? Check Your Stuffing Box

The Rain Catcher’s Guide

Boat Repairs for the Technically Illiterate

Boat Maintenance for the Technically Illiterate: Part 1

Whats the Best Way to Restore Clear Plastic Windows?

Mastering Precision Drilling: How to Use Drill Guides

Giving Bugs the Big Goodbye

Galley Gadgets for the Cruising Sailor

Those Extras you Don’t Need But Love to Have

UV Clothing: Is It Worth the Hype?

Preparing Yourself for Solo Sailing

How to Select Crew for a Passage or Delivery

Preparing A Boat to Sail Solo

On Watch: This 60-Year-Old Hinckley Pilot 35 is Also a Working…

On Watch: America’s Cup

On Watch: All Eyes on Europe Sail Racing

Dear Readers

Chafe Protection for Dock Lines

- Inside Practical Sailor

The DIY Solent Stay or Inner Forestay

Among the many rigging improvements I’m pondering for my Yankee 30 Opal the year ahead is installing a second forestay to allow more flexibility in my sail plan.

A few years ago we dove into this topic in a two-part series on headsails. Two articles discussed the advantages of retrofitting a sloop with an inner forestay so that a smaller headsail could be set in higher winds. In the first part, technical Editor Ralph Naranjo discussed the Solent stay. In the the second part if the series , sailmaker Butch Ulmer wrote about the advantages of an inner forestay or staysail stay.

A Solent stay is a stay that sets between the mast and the forestay. It connects to the mast at a point that is only slightly below the existing backstay, and meets on the deck only slightly abaft of the existing forestay. Under such an arrangement, the mast requires no additional support. The existing backstay provides adequate tension to counteract the loads of any sail that is set from the new stay. Because it requires no additional backstay support, a Solent stay is a slightly less expensive option than the more common staysail stay, and it offers many of the same advantages.

An staysail stay also sets between the mast and the forestay. As the name implies, a staysail stay is where you would set a staysail, although it is also commonly used for setting a storm jib. In this modification, the forestay joins to the mast much closer to the deck than the Solent stay, so that some support aft is needed, usually in the form of running backstays-backstays that can be tensioned when needed, and slacked out of the way when they are not required. The staysail stay meets at the deck further aft than the Solent stay, thus bringing the center of effort further aft, which is usually desirable in heavy weather.

Why add an additional stay? As we saw in part one of our report, a Solent sail or staysail stay resolves the difficulty in managing a boat in winds at the upper range of a roller-furling jib’s designed parameters (usually above around 30 knots). The failings of a roller-reefed headsail become especially apparent when trying to work to windward. Even the best-cut furling jib will not furl down to the same efficient shape of a sail designed to perform in higher winds. There is also the risk of the furling gear itself failing, or the jib unfurling to its full dimensions.

It is important to keep in mind that most coastal sailors don’t need to bother with either of these stays. If you a prudent near-shore sailor, a well-designed and constructed furling jib will usually serve just fine. Butch Ulmer’s report discussed several methods sailmakers use to improve the performance of the roller-furling headsail when reefed down. A padded foam luff, conservative sizing (so reducing the size of the furled sail), stiffer sail material, and more sophisticated construction can all help make the furled sail more efficient. However, several of the sailmakers we spoke with suggested that a second forestay would be a welcome addition aboard a boat that has aspirations for a long offshore cruise.

The most common question we were asked in the wake of our recent two-part series on headsails was, “How do I install an inner forestay or Solent stay?” Because either of these stays might one day be depended upon in the direst of circumstances, and because every boat presents different challenges for this project, it’s important to do your research and investigate other boats that have carried out this retrofit. Once you have a general idea of what features you like, consult a rigger for the initial design.

The rigger can also help you source the parts you need, and hopefully point out other details you might overlook, such as where to install the sheet leads, how to prevent corrosion of the new hardware, and what deck reinforcements might be required. If you are having a sail made for the new stay, then getting the sailmaker involved in the design will also help.

Once you have your measurements and hardware, you can carry out the installation, depending upon your ability. In some cases, you may need some fiberglassing skills, since the padeye/chainplate for the new stay must be adequately reinforced. Usually, fiberglass work can be avoided by transferring the load to the hull or a stout bulkhead, but as Brion Toss demonstrated in his recent article on the hidden causes of rig failure , this requires a general understanding of common installation errors and potential trouble spots.

For those who are considering an upgrade here are some other resources to consult as you begin your search.

- Don Casey’s This Old Boat Casey’s comprehensive book on upgrading an old sailboat dedicates several pages to adding an inner forestay. This comprehensive book is a must-have for anyone planning to turn a run-down sailboat into the pride of the marina. You can probably find a used copy on Amazon, but if you buy new from our bookstore , it helps support more Practical Sailor tests and special reports.

- PS Advisor Adding a Staysail Back in 1999, when former editor Dan Spurr was refitting his sloop Viva , he pitched this same question to naval architect Eric Sponberg, who offered some sage advice. This article also references three books that will be of help to anyone considering a retrofit, among the Understanding Rigs and Rigging by Richard Henderson.

- Whence Thou Comest, Highfield? We don’t know what was in the (former) editors water bottle when he came up with the headline for this test of quick releases for stays and shrouds back in 1999. After evaluating several devices, the test team concluded that ABI’s Highfield lever to be the best of the bunch. The company has since gone out of business, but the as the Rigging Company describes, three other worthy substitutes are now available. We routinely turn to the Rigging Company for advice on hardware and installations and its website has a section dedicated to installing an inner forestay that covers many of the hardware details, including devices for storing the inner forestay when not in use.

- Spar specialists Selden has a number of informative articles on rigging installation and maintenance. It offers step-by-step advice on installing an inner forestay fitting (nose tang) on the mast. For those who are dealing with a classic boat, fabricating their own chainplates or tangs, or simply enjoy digging into archaic, yet still valuable advice. Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design offers tips on calculating loads and fabricating hardware. It is still relevant enough to pick up from a used book store. Rig-Rite also offers a selection of staysail tangs.

- Rigger and sailmaker websites In addition to its discussion of stay releases the Rigging Company has additional information on adding a Solent stay. Brion Toss’s Spartalk discussion board (log-in required) has several threads dealing with inner forestays, Solent stays, and related hardware. Among them is Toss’s rant against the ABI forestay release . He prefers the babystay releases from Wichard (see page 9 of the catalog), available in wheel, ratchet, or lever designs, depending on the size of the boat. And sailmaker Joe Cooper describes a lightweight Solent stay retrofit using fiber instead of wire for the stay. (Because of unknowns regarding fiber stays, PS still prefers wire for this use.)

- Owner retrofits A number of blogs and archive articles from old magazines offer insight into what a retrofit entails. The Windrope family has done an excellent job documenting the addition of a Solent stay to Aeolus , their Gulf 32 Pilothouse sloop.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

On watch: this 60-year-old hinckley pilot 35 is also a working girl.

Dear Darrell,

A smaller headsail, or storm jib is indeed preferable to rolling up a Genoa when heading windward in winds over even 20 knots But adding it on as a retrofit brings up the issue of the lines to control it. Ideally it could be fitted on to a self-tacking rail, but these are quite awful if not installed in the original design, just one more thing to trip over and mess up a clean foredeck. I had researched this and apparently there are a number of simple solutions using a rigging set up based on the foot of the mast and clew of the jib, providing just one line astern through a deck organiser to the cockpit ‘piano’. This line simply controls how tight the jib will be and can be left alone when tacking upwind to act as self tacking jib. We sail in the Aegean where wind can be anything from ‘nothing’ to 35 knots sometimes with quick changes, so it pays to be adaptable. If you have any comments or recommendations for such rigs, it may well interest other readers as well and indeed myself as well.

I had a cutter, a Kelly Peterson 44. Great sailing cruiser. However, I would have rather have had a Solient over the traditional cutter. Not even including that yes, it required running back stays, the boat would balance better with a rolled jib over the staysail alone, even with double reefed main. Of course the set of the rollered 110 was not that great. A solient would have been my preference. Walter Cronkite had an interesting custom arrangement on his boat. He had his jib and solient on two stays separated an appropriate distance to properly function and both were on a yoke that would swivel. Just one attachment at masthead and one on stem. Of course hi-thrust bearings on both. The active sail would swivel aft when in use and the inactive would swivel forward complete out of the way! Clever arrangement. Yes, you would get a little “dirty” air from the inactive but everything is a trade off. Probably one that I would take if I could afford all that custom work.

I also have a cutter; CSY 44. When tacking, the jib would not come thru the innerforestay cleanly and would hang up. I installed a quick disconnect and when I know I will be beating it is set up that way. Makes it a lot easier to tack. I see hanging up as a problem with a the double forestay unless you carry the smaller sail on the most forward. However, is this where you want a storm jib? Should I need the storm jib, the staysail stay is the perfect place.

We had a custom rig built for our boat, a Valiant 40′ cutter with a bowsprit that sets the forestay two foot further forward. It was designed to allow both a Solent sail and/or a Staysail. We sail the boat as a Cutter and have no problem at all with the inner forestay interfering with the genoa and jib sheet, (just backwind the staysail until the clew of the genoa has moved to the leward side). The Staysail is roller-reefing too, and is small and very easy to handle, even in a blow. (don’t need the self-tending feature.) When in high winds, the furling staysail is perfect. As for the solent, I consider it more appropriate for a drifter, perhaps wing & wing with the genoa for downwind sailing.

Great Article, Darrell. Your advice to consult a rigger is spot on to address mast support issues. I helped deliver a beautiful Outbound to the Caribbean several years ago from New England. Once we turned south, the skipper set the hank-on Solent staysail on the inner stay. Sweet indeed. Easy to hoist and dowse. Nothing complex about a hank-on headsail. They go up and come down every time.

Interesting article, Darrell. Thank you. But my lord, does anybody proofread this stuff?

As I research adding a solent stay on our Tartan 27 I find many riggers are recommending a 4 to 1 purchase rather than a Highfield lever. They like the ability to adjust the tension at will. For our little sloop with a tabernackle the solent is much simpler and would remain stowed most of the time.

As a cutter sailor I must make a point of clarification. Installing an inner stay or staysail to your sloop design does NOT make it a cutter. A true feature of a cutter is that the mast is further aft than on a sloop in addition to the staysail feature. That is paramount to moving the center of effort further aft as the designer intended.

I have seen a number of cutter owners removing the staysail to sail the boat as a sloop simply because they don’t know how to sail it properly as a cutter. On the other hand, one unnamed circumnavigational sailor calls her boat a cutter when it is simply a sloop with inner stay…the manufacturer never made that boat design as a cutter. Last but not least one prominent cutter manufacturer offered their design as both a sloop and as a cutter; I called them to verify the fact that the mast was still in the original design location as a cutter. Can you begin to imagine what would be involved to design and build a sailboat with optional mast locations or even modify a sailboat from one rig location to the other?

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

What’s the Best Sailboats for Beginners?

Why Does A Sailboat Keel Fall Off?

The Perfect Family Sailboat! Hunter 27-2 – Boat Review

Pettit EZ-Poxy – How to Paint a Boat

Latest sailboat review.

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

- Sails & Canvas

- Hull & Structure

- Maintenance

- Sailing Stories

- Sailing Tips

- Boat Reviews

- Book Reviews

- The Dogwatch

Select Page

Staying Power – Adding an Inner Forestay

Posted by Ed Zacko | BWI Award-Winning Articles , Projects , Rigging

Adding an inner forestay expands sail plan options and can make for better boathandling.

W hen my wife, Ellen, and I began our search for an ocean-going cruising boat, high on our list of requirements was that it be a cutter—a simple, single-mast rig with one mainsail and two headsails and a mast set further aft than on a sloop.

The cutter has several benefits. The larger foretriangle allows the total sail area to be proportioned more equally between the three sails. Two ready headsails offer flexibility and efficiency, precluding the hassle of swapping a large genoa for a smaller jib when conditions warrant. The dedicated intermediate stay set aft and closer to the mast permits a staysail in strong winds, and pairing it with a deeply reefed main (or trysail) better balances the helm. And the added forestay offers security when going to windward and makes for easy short tacking in harbors under staysail alone.

Unfortunately, we never found a cutter that satisfied our other requirements. And, when we fell in love with the Lyle Hess-designed Nor’Sea 27, we bought a bare hull and deck to complete in our backyard, figuring we could fairly easily build a cutter rig for it. Our ideas were quickly dashed by Lyle himself. He pointed out that designing and building a cutter rig would result in a domino effect of additional changes that just weren’t worth it.

So, we went sailing on Entr’acte the sloop, and four years later, found ourselves in Portugal anchored next to world-cruising veterans Hal and Margret Roth. Their sloop, Whisper , proudly sported an intermediate forestay they had added, which Hal said provided nearly all of the advantages of a full-fledged cutter. I wondered about doing the same aboard Entr’acte . “It won’t be a cutter,” Hal said, “but it will be pretty close. You just have to be very clever about how you do it—and keep things simple!”

That meeting and conversation came full circle as Ellen and I prepared Entr’acte for our second voyage and debated adding roller furling. An intermediate stay like the Roth’s, we reasoned, would offer redundancy if the headsail furler broke, and it would let us set a smaller headsail in windy conditions, taking the burden off that single headstay.

Attaching an inner forestay between the mast and deck would be easy. Our challenge was to position it correctly to gain the best possible sail plan options and to make it easy to stow when not in use.

Forestay Positions

In the forward position, the stay is attached to a permanent toggle installed in the stemhead fitting’s aft-most opening. The stay is just clear of the furling drum and allows for easy hoisting and lowering of sails.

Our inner forestay would have three positions. The first would attach immediately to the main stemhead fitting just aft of the roller furling drum. In this position we could hank on the 110 percent working jib or a large nylon drifter. This would also be a better location to attach the sliding tack strap of our new asymmetric cruising chute. This strap is designed to wrap around a furled genoa and slide up and down to adjust the shape of the cruising chute’s luff, which might be all right for a Sunday afternoon. But for long passages we did not like the idea of that strap chafing mile after mile on a furled, expensive genoa and imparting needless wear on furling gear bearings for thousands of miles when not in use. Far better to have that tack strap ride on its own forestay to save the wear and tear.

The second position was 3 feet back from the primary forestay. From this position we could set our storm jib as a staysail for short tacking into an anchorage. It would also improve the boat’s handling in heavy winds. As a mainsail is reefed, the length of the foot decreases and moves forward, shifting that sail’s center of effort toward the mast. But when a headsail is furled under the same conditions, its center of effort remains unchanged, so the net movement of the center of effort is forward, which tends to unbalance the helm. Setting a headsail 3 feet further aft brings that sail’s center of effort aft, helping to balance the helm in heavier winds.

The staysail rigged, with the inner stay set in the aft position. To use this, Ed rolls in the genoa and stows the sheets forward, out of the way.

The third position would be stowed for when this stay is not needed. In our case, the wire, detached from its turnbuckle, was just the right length to clip onto a 1⁄4-inch turnbuckle attached to a bail on the starboard middle stanchion. The turnbuckle would provide just enough tension to keep it from slopping around, allowing the stowed stay to serve also as a stable handhold when needed. Attached in a straight line to the stanchion, the new stay would be out of the way until needed with no bends or extra hardware.

Fortuitously, measurements landed the aft attachment point for the new headstay between the two large cleats at the narrowest clear point on the foredeck. This is where the deck is least likely to flex under load, and the foredeck remains clear.

Stay Installation

Deciding where exactly to mount the stay was a product of trial and error with cheap line. We finally determined it was best to mount the deck attachment 3 feet aft of the main stemhead fitting and the mast band 3 feet below the masthead. This positioning would keep the new stay parallel to, and far enough away from, the main forestay to prevent the two from tangling with each other, a common problem with double forestays. With the judicious use of extra toggles, we could easily move the lower attachment point from the fore to aft positions, ensuring it fit perfectly in either location.

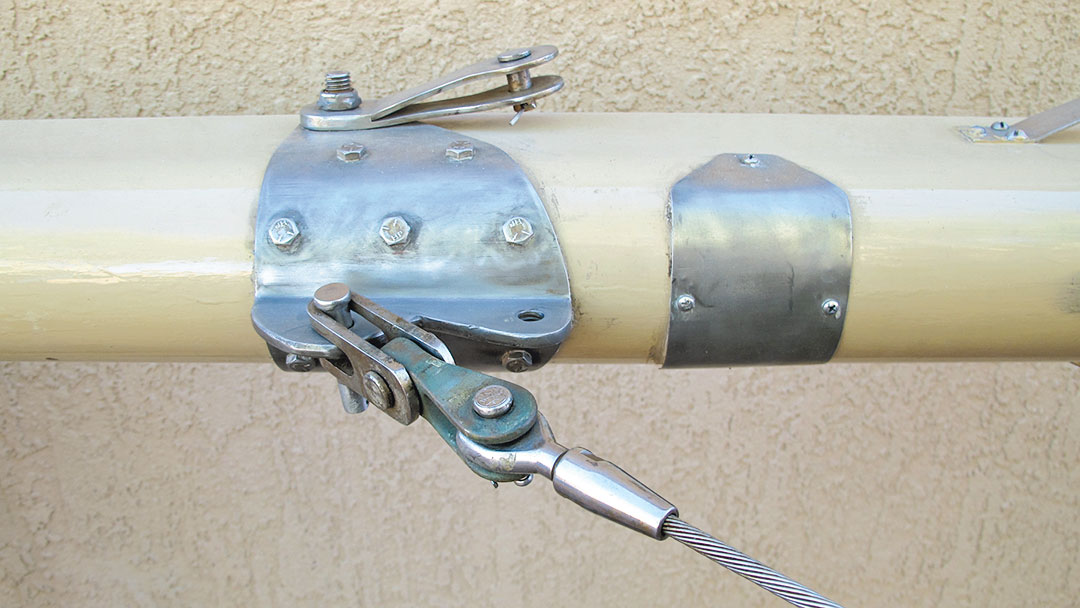

The mast band is attached with 1⁄4 x 20 machine screws drilled and tapped. It’s further secured through a 1⁄2-inch stainless steel stud that passes completely through the mast and compression tube. The stud also provides an attachment for tangs for running backstays.

The standing rig consisted only of the forestay and a 7⁄16-inch bronze turnbuckle. (The price of a proper “highfield lever” to tension the new stay took our breath away. We opted instead for a spare turnbuckle with toggle and quick release pins. Simple, yet effective.)

The running rig was simply a halyard and two jib sheets. We didn’t add additional winches or lead blocks, figuring that both headsails would never be used on the same tack at the same time. When we wanted to hoist a staysail, we employed the unused genoa winch.

Ed added a robust deck plate under the foredeck with an eye to accept a turnbuckle and wire that transfers the load to the foremost interior bulkhead, which is glassed to the hull.

Below decks, we installed a 1 x 6-inch white oak plank which completely traversed the deck. This one large beam effectively increased our deck thickness and served as a substantial backing plate not only for the forestay but for the deck cleats as well. This was a distinct improvement from the two smaller individual backing blocks we had before.

A 1 x 6-inch oak plank added beneath the foredeck replaced two smaller backing blocks and beefed up the entire area where two bow cleats and the forestay are attached.

To prevent leaks and mold, we thoroughly bedded the oak beam and both deck plates with Dolphinite compound. We always use Dolphinite whenever we bed wood to fiberglass or wood to metal because, unlike other compounds, it soaks into the wood to best seal out water. It also boasts anti-fungicidal properties that prevent rot. Dolphinite never gets hard and has always proved easy to disassemble, even after many years in place.

Putting it to Work

Over time we have experimented with the inner forestay and have learned a lot. We discovered an especially interesting setup on our 2003 Atlantic crossing. The wind was in just the wrong place, not quite dead astern but far enough on the quarter so the mainsail completely blanketed the genoa, rendering it quite useless. Poling out the genoa on the other side for a dead run would require a course change 15 degrees to port of our rhumb line. To get the genoa to draw properly would likewise mean a 15- or 20-degree alteration to starboard.

Because of the relatively light wind and pronounced cross swell, the large cruising chute was not a viable option. We certainly could have sailed a day at a time gybing onto alternating tacks, but there had to be a better solution. Finally, we came onto our desired course, trimmed the mainsail and genoa on starboard tack, hoisted our 110 percent working jib as a staysail with the inner forestay in aft position, and poled it out to starboard. Because the jib was small and sailing by the lee, it did not drive us very well, but it did funnel the wind quite nicely into the large genoa, tricking it into drawing properly. Once set, we continued comfortably on our way for the next five days.

Our inner forestay has been a rousing success with results far better than we had imagined. It’s a simple and economical addition to our cruising rig and gives us most of the advantages of a proper cutter. After sailing thousands of miles with this system, the only improvement we might make would be to add a dedicated halyard winch.

Storing the Stay

When it came to storing our inner stay when not in use, we got lucky and were able, by removing its turnbuckle, to attach it to a stanchion with a shorter turnbuckle and provide enough tension to keep it safely snug.

But, storing the inner forestay is usually easier said than done. Once disconnected at the deck fitting, the stay is too long to stow in a straight line from the mast fitting. Bending the stiff and inflexible 1 x 19 rigging wire causes work hardening, which dangerously weakens the wire. If your wire stay is too long to stow in a straight line, it must be led around a large, smooth radius before it is put under tension for stowage.

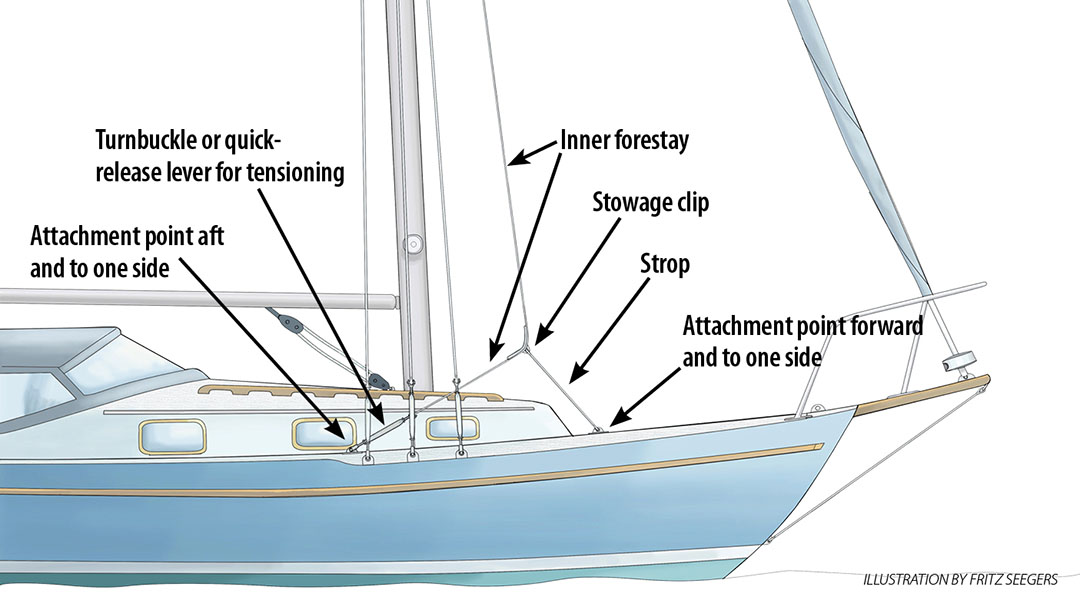

A stowage clip, also known as an inner forestay clip or inner stay storage bridle, solves the problem. This simple piece of gear clips onto the stay and features an eye for a strop that can be used to draw the stay away from the mast. With the strop leading forward to one anchor point on deck, the stay can be tensioned with its turnbuckle to a second attachment point slightly aft.

Wireless Options—Jamie Gifford

An inner forestay adds options for sail plan and mast control. But the location of an inner forestay can mean that it’s sometimes an inconvenience when not in use. It can interfere with tacking or prohibit dinghy storage on the foredeck. Making the inner forestay removeable alleviates some of these drawbacks but creates new challenges. Stowing the detached forestay can be difficult if long length requires deflecting wire around to its anchor point. And once stowed, the stay may bang into the mast and spreaders or chafe against a tightly sheeted genoa.

Using high-strength, low-stretch line instead of traditional wire mitigates these problems.

Dyneema or Spectra line (same fiber, different manufacturers) offers several excellent characteristics for this application. Single-braid construction is very easy to splice. It has a soft hand and is so lightweight that it floats. This makes for easier stowing than wire and less chafing against rig and sail surfaces. These high-tech lines have good UV resistance, with tests revealing that 10 years of exposure degrades the material by about 50 percent. This isn’t insignificant, but stainless steel also degrades (from corrosion and work hardening), and the line is easier to inspect.

All materials have their Achilles’ heel. For these lines, it’s chafe. Though very slippery and chafe resistant, an edgy object pressed against a loaded low-stretch line will damage it quickly. These same lines are available as double-braided and with a polyester cover, but while these features offer some chafe protection and UV blocking, they also are harder to splice and less slippery (important when hoisting/dropping sails). In my opinion, the gains don’t warrant the compromises. It’s best to minimize chafe by attaching sails using soft hanks of either webbing loops or soft shackles (made from Dyneema or Spectra) and to keep running gear from wearing against a low-stretch line stay.

On Totem , the Stevens 47 that my wife, Behan, and our three children circumnavigated on, the removeable inner forestay is made from Dyneema SK75. Three grades of Dyneema have appropriate strength and stretch characteristics for this application: SK75, SK78, and SK90. One-quarter-inch-diameter SK75 has a breaking strength of 8,600 pounds.

Totem also has a removable Solent stay, set parallel and close to the forestay and made from Dynex Dux. This is Dyneema line put through additional treatment that makes it even stronger and with lower constructional stretch.

In sizing Dyneema or Dynex Dux, I recommend increasing the diameter to account for the inevitable UV damage. And splice the ends around a thimble. No knots! Thimble-less or knotted ends result in tight bend radiuses that significantly weaken the line.

High-tech line is a nice solution for a removable inner forestay and has many other applications onboard. And besides, who doesn’t like to show off a little DIY traditional ropework in techy materials?

About The Author

Ed Zacko is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. Ed, the drummer, and Ellen, the violinist, met in the orchestra pit of a Broadway musical. They built their Nor'Sea 27, Entr'acte, from a bare hull, and since 1980 have made four transatlantic and one transpacific crossing. After spending a couple of summers in southern Spain, Ed and Ellen shipped themselves and Entr’acte to Phoenix, where they have refitted Entr'acte while keeping up a busy concert schedule in the Southwest US. They recently completed their latest project, a children's book, The Adventures of Mike the Moose: The Boys Find the World.

Related Posts

Sail Covers

September 1, 2020

Renovating a RIB

January 1, 2018

Heating Honcho

January 4, 2024

Knife Storage on a Sailboat

November 8, 2021

Current Edition

Join Our Mailing List

Get the best sailing news, boat project how-tos and more delivered to your inbox.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

- News & Views

- Boats & Gear

- Lunacy Report

- Techniques & Tactics

MODERN SAILBOAT DESIGN: Form Stability

Stability, fundamentally, is what prevents a boat from being turned over and capsized. Whether you are a cruiser or a racer, it is a desirable characteristic. A boat’s shape, particularly its transverse hull form, has an enormous impact on how stable it is. This so-called “form stability” is one of the primary reasons you should be interested in the shape of a boat’s hull.

The basic principle is self-evident: an object that is wide and flat is harder to overturn than one that is narrow and round. With this in mind, you can usually see at a glance what hull shapes have the greatest form stability. Wide hulls are inherently more stable than narrow ones; given two hulls of equal width, the one with less deadrise and a flatter bottom is more stable than one with more deadrise and a rounder bottom.

The controlling dimension, when considering width, is always waterline beam. Do not jump to conclusions based on a boat’s published maximum beam, as boats with the same maximum beam can easily have very different waterline beams. Another important factor is how a boat’s beam is distributed along the length of its hull. A hull that carries more waterline beam into its bow and stern sections–that is, a hull with a larger waterplane–has more form stability than a hull with a wide midsection and narrow ends. The classic example of the latter are the IOR boats that dominated racing during the 1970s. Because the IOR rating rule favored beamy boats but measured beam only in the midsection, designers thought they could have their cake and eat it, too. By making their boats fat in the middle they could gain a rating advantage; by pinching the ends they could reduce displacement and wetted surface area. Such hulls, however, as demonstrated during the 1979 Fastnet Race, are often not very stable.

Form stability is an important component of what is termed initial stability, which refers to a boat’s ability to immediately resist heeling when pressure is applied to its sails. A boat with lots of initial stability is said to be stiff; one with little initial stability is tender. Stiffness is a desirable feature, as a boat never sails as well when it’s heeled way over on its ear. The keel’s effective area and draft and its capacity for generating lift are reduced, as are the effective height and area of the sail plan (by about 10 percent, for example, when a boat is heeled to an angle of 25 degrees). A stiff boat that stays more upright not only retains more keel and rig efficiency, it can also stand up to a larger sail plan in the first place. In many cases, particularly if a boat is light, this negates any loss of performance caused by an increase in beam and wetted surface area.

Stiff boats with good form stability in one sense are more comfortable, especially for novice sailors, than boats that heel easily. In another sense, however, they can be very uncomfortable. Though they are rolled to less severe angles, they snap back from those lesser angles more quickly and abruptly than boats with less form stability that are rolled to greater angles. The resulting motion can seem jerky and violent, and this is reflected in a boat’s motion-comfort ratio . This quick motion, combined with the tendency of a flat-bottomed boat to pound in a steep head sea, may lead some to conclude that there can be such a thing as too much form stability.

The most important thing to remember about form stability is that it does not translate into ultimate stability. A sailboat’s hull form can help it resist heeling up to a point, but past that point all bets are off. A boat that depends too much on form stability to stay upright will be capable of supporting an enormous sail plan in moderate conditions, but when caught in a sudden squall with all its sail up, it can be laid over and capsized very quickly.

Capsized Open 60s can potentially be as stable upside down as they are right-side up. These days boats most undergo a righting test before competing

In a worst-case scenario, after a hull like this has capsized, its form stability may even help keep it inverted. Fans of singlehanded ocean racing will recall a dramatic series of Open 60 capsizes in the mid- to late-1990s. These extremely wide, flat monohulls, designed to surf at high speeds off the wind in the Southern Ocean, stayed upside down after being flipped over in spite of the very deep (or tall, as the case may be) ballast keels attached to their bottoms.

The ultimate in form stability

Multihulls, of course, rely entirely on form stability to stay upright. They are extremely stiff, and it takes an enormous amount of energy to heel them to any appreciable degree. Once pushed to the limit, however, they must flip over and must remain flipped over until an even greater amount of energy arrives to right them. Monohull cruisers, of course, point to this as the Achilles heel of the multihull. Multihull cruisers respond by noting that in a worst-case scenario their boats at least will still be floating (albeit upside down) while the monohull sailor’s craft will be sitting (albeit somewhat upright) at the bottom of the sea.

Related Posts

- BAYESIAN TRAGEDY: An Evil Revenge Plot or Divine Justice???

COMPREHENDING ORCAS: Why the Heck Are They Messing With Sailboats?

Capsize is still better than swimming

I delight in designing model gaff rig yachts that carry a large sail plan, so this article was extremely helpful. This will be my third boat, on which I intend the rig to massively overhang the hull length fore and aft, so waterline beam will be critical. Thank you very much.

Damn Paul. Can we see a photo of one of those models???

Sorry Charles I ‘lost ‘ this site – so never saw your comment. My previous boat was based on a pilot cutter style with a slightly adventurous keel shape in order to deepen it and get the weight down low. I’ve spent the last 8 months on this third boat with a much greater waterline beam and a deeper bulb keel with the hope that it can carry 30 percent more sail. It has turned out a bit bulky looking but I’ll be interested to see how she performs – should be ready in a month or so. I see this site doesn’t enable upload of pics otherwise I’d be pleased to show you. Thanks for your interest.

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Please enable the javascript to submit this form

Recent Posts

- MAINTENANCE & SUCH: July 4 Maine Coast Mini-Cruz

- SAILGP 2024 NEW YORK: Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous

- MAPTATTOO NAV TABLET: Heavy-Duty All-Weather Cockpit Plotter

- DEAD GUY: Bill Butler

Recent Comments

- Charles Doane on BAYESIAN TRAGEDY: An Evil Revenge Plot or Divine Justice???

- Nick on BAYESIAN TRAGEDY: An Evil Revenge Plot or Divine Justice???

- jim on BAYESIAN TRAGEDY: An Evil Revenge Plot or Divine Justice???

- Fred Fletcher on TIN CANOES & OTHER MADNESS: The Genius of Robb White

- Brian on THE BOY WHO FELL TO SHORE: Thomas Tangvald and Melody (More Extra Pix!)

- August 2024